CONTENTS

- Basics

- Epidemiology

- Clinical presentation

- Laboratory studies

- Radiology

- Bronchoscopy

- Biopsy (surgical vs. cryobiopsy)

- Differential diagnosis

- Approach to diagnosis

- Treatment

- Prognosis

- Other related topics:

- Questions & discussion

abbreviations used in the pulmonary section:

- ABPA: Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis 📖

- AE-ILD: Acute exacerbation of ILD 📖

- AEP: Acute eosinophilic pneumonia 📖

- AIP: Acute interstitial pneumonia (Hamman-Rich syndrome) 📖

- ANA: Antinuclear antibody 📖

- ANCA: Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies 📖

- ARDS: Acute respiratory distress syndrome 📖

- ASS: Antisynthetase Syndrome 📖

- BAL: Bronchoalveolar lavage 📖

- BiPAP: Bilevel positive airway pressure 📖

- CEP: Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia 📖

- COP: Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia 📖

- CPAP: Continuous positive airway pressure 📖

- CPFE: Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema 📖

- CTD-ILD: Connective tissue disease associated interstitial lung disease 📖

- CTEPH: Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension 📖

- DAD: Diffuse alveolar damage 📖

- DAH: Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage 📖

- DIP: Desquamative interstitial pneumonia 📖

- DLCO: Diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide 📖

- DRESS: Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms 📖

- EGPA: Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis 📖

- FEV1: Forced expiratory volume in 1 second 📖

- FVC: Forced vital capacity 📖

- GGO: Ground glass opacity 📖

- GLILD: Granulomatous and lymphocytic interstitial lung disease 📖

- HFNC: High flow nasal cannula 📖

- HP: Hypersensitivity pneumonitis 📖

- IPAF: Interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features 📖

- IPF: Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis 📖

- IVIG: Intravenous immunoglobulin 📖

- LAM: Lymphangioleiomyomatosis 📖

- LIP: Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia 📖

- MCTD: Mixed connective tissue disease 📖

- NIV: Noninvasive ventilation (including CPAP or BiPAP) 📖

- NSIP: Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia 📖

- NTM: Non-tuberculous mycobacteria 📖

- OP: Organizing pneumonia 📖

- PAP: Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis 📖

- PE: Pulmonary embolism 📖

- PFT: Pulmonary function test 📖

- PLCH: Pulmonary Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis 📖

- PPFE: Pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis 📖

- PPF: Progressive pulmonary fibrosis 📖

- PVOD/PCH Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease/pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis 📖

- RB-ILD: Respiratory bronchiolitis-associated interstitial lung disease 📖

- RP-ILD: Rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease 📖

- TNF: tumor necrosis factor

- UIP: Usual Interstitial Pneumonia 📖

- Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is the most common idiopathic interstitial lung disease. It is an idiopathic, chronic disorder causing progressive lung fibrosis, which isn't associated with any systemic or connective tissue disease.

- Most interstitial lung diseases cause inflammation, which eventually progresses to fibrosis. IPF is somewhat unusual in that it progresses directly to fibrosis (with no intervening inflammation). This explains why anti-inflammatory therapies are ineffective for IPF.

relationship between UIP and IPF:

- Usual interstitial pneumonitis (UIP) refers to a histological and radiological pattern that is associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, as well as other related fibrotic lung diseases:

- IPF = idiopathic UIP.

- IPF is a subset of all patients who have UIP.

- IPF refers to a clinical disease (whereas UIP describes a histologic and radiological pattern).

- UIP may also result from other disorders (e.g., connective tissue disease). This will mimic IPF.

- IPF = idiopathic UIP.

- (In clinical practice, these terms are used somewhat interchangeably.)

- IPF is a disease of aging:

- Most patients are >50-55 years old.

- Age <50 years old makes IPF much less likely. (36630775) Younger patients are more likely to have connective tissue-related interstitial lung disease. Another cause of IPF in younger patients is short telomere syndromes. 📖

- Age >75 years old has a high positive predictive value for IPF diagnosis.(20056903)

- Male predominance (75%).

- Associated with smoking:

- Family history:

- IPF may be familial in perhaps ~8% of patients.

- If present, a family history of fibrotic lung disease is a strong risk factor. (36702498)

symptoms

- IPF usually presents with insidiously progressive dyspnea on exertion.

- Patients may rapidly deteriorate and develop acute respiratory failure – this is discussed further in the chapter on acute exacerbation of interstitial lung disease: 📖

- There is often a dry cough.

- Constitutional symptoms are uncommon.(Murray 2022)

examination

- Velcro rales are present at the lung bases in >85% of patients. These typically occur at end-inspiration. They sound like ripping Velcro, or like walking on dry crunchy Vermont snow.(37055085) With disease progression, rales may extend to the upper lung zones as well.(Fishman 2023)

- Clubbing is seen in ~40% of patients. (Shah 2019)

- In advanced disease, pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular dysfunction may cause peripheral edema.

laboratory evaluation for patient with possible IPF

- Complete blood count with differential.

- Liver function tests.

- Serologies to evaluate for connective tissue disease:

- Extractable Nuclear Antigens (ENA panel) – RNP, Sm, SSa, SSb.

- MyoMarker panel – evaluation for idiopathic inflammatory myositis.(34488971) This is a send-out test to the Mayo Clinic (test ID FMYO3).

- Additional labs that require a specific order:

- Antinuclear antibody (ANA).

- RF (rheumatoid factor) and anti-citrullinated protein autoantibodies (ACPA).

- Anti Scl-70.

- Anti-double stranded DNA.

- Creatinine kinase (CK).

- Aldolase.

- CRP (C-reactive protein).

- Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA).

expected results for patients with IPF

- Normal laboratory studies would support a diagnosis of IPF.

- However, IPF patients may have positive ANA (antinuclear antibody) or RF (rheumatoid factor) in ~25% of patients.

- Patients with short telomere syndromes may display laboratory evidence of:

- Myelodysplastic bone marrow failure (e.g., thrombocytopenia, anemia, macrocytosis).

- Cirrhosis.

chest radiograph

- Radiography is usually normal initially.

- Lung volumes may be reduced.

- Subpleural reticulation may be seen, with a basilar predominance.

- Evidence of pulmonary hypertension may be present.

CT findings: four cardinal findings that support an IPF diagnosis:

- [1] Distribution is:

- Patchy (geographic heterogeneity).

- Bilateral.

- Subpleural predominant (nearly all patients).

- Basilar predominance in ~80% of patients (in ~15% all lung zones are involved to a similar degree, but this should also raise the possibility of rheumatoid arthritis 📖).

- [2] Reticular abnormalities (irregular thickening of interlobular septa).

- [3] Fibrosis: Honeycombing +/- traction bronchiectasis.

- Honeycombing is the single most specific finding to support IPF. (However, honeycombing can be seen in other disorders, as discussed here: 📖)

- Traction bronchiectasis and bronchiolectasis typically has a beaded, varicoid appearance.

- [4] None of the following features (which are inconsistent with IPF):

- Upper or mid-lung predominance (consider fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonia, connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease, sarcoidosis).

- Peribronchovascular predominance with subpleural sparing (consider nonspecific interstitial pneumonia).

- Subpleural sparing (consider nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, organizing pneumonia, or smoking-related interstitial pneumonia).

- Extensive GGO (ground glass opacity):

- Some ground glass opacity is usually present in IPF, but it should be limited.

- In IPF, GGO usually occurs in areas with a finely reticulated pattern and traction bronchiectasis/bronchiolectasis. This form of “textured” GGO reflects alveolar fibrosis, rather than acute alveolitis. (36630775) Over time, these areas of ground glass opacity usually progress to frank fibrosis (reticulation and honeycombing). (Walker 2019)

- Predominant ground glass opacities makes a diagnosis of IPF unlikely. However, an exception to this is an exacerbation of IPF, wherein the amount of ground glass opacity may increase dramatically.

- Profuse centrilobular micronodules.

- Discrete cysts (multiple, bilateral, and away from areas of honeycombing).

- Diffuse mosaic attenuation or air trapping (bilateral, in three or more lobes – consider hypersensitivity pneumonitis)

- Consolidation in bronchopulmonary segment(s) or lobe(s).

other radiological features:

- Pulmonary ossification – calcified micronodules may be found within areas of fibrosis. This may be seen in other fibrosing interstitial lung diseases, but is more common in IPF. (36630775)

- PPFE (pleuropulmonary fibroelastosis) may be seen in the lung apices.

- Pneumothorax may occasionally occur due to rupture of a fibrotic area.

- Mediastinal lymphadenopathy is often noted, but usually involves only 1-2 nodal stations and lymph nodes are generally <15 mm. This doesn't correlate with disease activity overall. The presence of bulky or extensive lymphadenopathy would argue for an alternative diagnosis.

- Effusion is generally absent (although effusion may be caused by another pathology, such as heart failure).

classification of CT findings

- Based on the overall constellation of findings, CT scans may be classified roughly into four categories:

- Typical of IPF:

- All four of the cardinal features listed above are present.

- Surgical lung biopsy reveals a UIP pattern in ~95% of patients.

- Probable IPF:

- Features #1, #2, and #4 are present (but lacking fibrosis).

- Surgical lung biopsy reveals a UIP pattern in ~85% of patients (especially patients >65 years old, with tobacco exposure, and no alternative explanation).

- Indeterminate for IPF:

- (1) Features suggestive of IPF, for example:

- Fibrosis (e.g., honeycombing, traction bronchiectasis).

- Discrete subpleural reticulations, without definite signs of fibrosis.

- (2) Criteria for typical/probable IPF are not met.

- (3) There shouldn't be signs suggesting an alternative diagnosis.

- (1) Features suggestive of IPF, for example:

- Inconsistent with IPF:

- Features inconsistent with IPF are present (as listed in #4 above).

- Surgical lung biopsy might reveal a UIP pattern, but this is much less likely (and will vary depending on the specific clinical and CT scan findings).

radiologic differentiation between IPF vs. NSIP

- This is discussed further here: 📖

role of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL)

- Bronchoscopy can help exclude some alternative diagnoses. The yield is inversely related to the likelihood that the patient has IPF.

- Guidelines recommend bronchoalveolar lavage for patients with possible IPF, if:

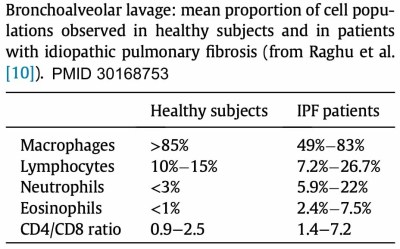

differential cell count from the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL)

- Neutrophilia is typically seen.

- Mild eosinophilia may be seen (which might be a poor prognostic finding).

- IPF generally causes a paucity of lymphocytes.

- Significant lymphocytosis (>30%) would strongly argue against a diagnosis of IPF. This may suggest the possibilities of cellular nonspecific interstitial pneumonia or hypersensitivity pneumonitis. However, there are numerous diseases which may cause lymphocytosis, as listed here: 📖

- If lymphocytosis is absent (<~15%), this is consistent with IPF. However, this may be seen with other interstitial lung diseases, such as fibrotic NSIP (nonspecific interstitial pneumonia).

forceps transbronchial biopsy is not recommended

- Forceps transbronchial biopsy yields tissue samples which are too small to clarify the diagnosis of IPF. However, these biopsies still expose the patient to substantial risk (e.g., 10% rate of pneumothorax). (36630775)

- Guidelines do not recommend the use of forceps biopsy in patients with suspected IPF. (36630775)

who might benefit from biopsy?

- Biopsy is avoided if imaging and clinical features are strongly suggestive of IPF (e.g., CT scan shows typical or probable UIP pattern within a clinical context suggestive of IPF). If the patient does indeed have IPF, lung biopsy is dangerous (since this may provoke an acute exacerbation of IPF in ~5% of patients).

- Among ~10-30% of patients, a lung biopsy is used to support the diagnosis of IPF (e.g., for younger patients with nonspecific clinical and imaging features). (Shah 2019) The greatest benefit of biopsy is when it reveals an alternative diagnosis that may be more treatable than IPF (e.g., sarcoidosis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, organizing pneumonia).

- 💡 Note that a biopsy alone cannot diagnose IPF!

- It's essential to recognize that finding UIP on surgical lung biopsy doesn't establish a diagnosis of IPF. The presence of UIP on a surgical biopsy only establishes a diagnosis of IPF if the clinical and radiological patterns also fit a diagnosis of IPF (discussed further below).

- In practice, biopsies often show a variety of different pathological findings, which may be nonspecific overall (e.g., “possible UIP pattern”).

- ⚠️ Multidisciplinary input should be obtained prior to any invasive testing. (36702498)

surgical biopsy vs. cryobiopsy

overview of cryobiopsy vs. surgical biopsy

- Cryobiopsy is an interventional pulmonology procedure that involves insertion of a cryoprobe into the lung parenchyma, rapidly freezing the surrounding lung tissue, and then removing the frozen tissue. The overall concept is grossly similar to a bronchoscopic forceps biopsy, but the tissue specimen is larger.

- Surgical biopsy generally involves single-lung ventilation and VATS (video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery). This is more invasive than a cryobiopsy, but it allows for obtaining larger samples of tissue.

- Recent guidelines recognize both cryobiopsy and surgical biopsy as valid approaches to obtain histopathological specimens. (35486072)

- Both procedures (surgical biopsy and cryobiopsy) have similar indications (as discussed above).

contraindications to biopsy:

- Contraindications to surgical biopsy may include: (36630775)

- Rapid deterioration of the disease (unplanned biopsy).

- Low respiratory reserve (FVC <60%, or DLCO < 35%).

- Oxygen therapy at rest.

- Pulmonary hypertension.

- Significant or multiple comorbidities.

- Age >75 years old.

- Immunosuppression.

- Contraindications to cryobiopsy may include: (35486072)

- Severe lung dysfunction (e.g., FVC <50%, DLCO < 35%).

- Pulmonary hypertension with estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure >40 mm.

- Coagulopathy that is uncorrectable, including:

- Platelets <50 b/L (absolute contraindication).

- Treatment with anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents (aspirin is a relative contraindication, whereas clopidogrel is an absolute contraindication).(36630775)

- Significant hypoxemia (PaO2 <55-60 mm).

yield

- Cryobiopsy has a yield of ~84%, with a sensitivity of ~87% and specificity of ~57%.(36630775) The yield of cryobiopsy is maximized by obtaining at least three samples. (35486072)

- Surgical biopsy has a yield of ~93%, with a sensitivity of ~91% and a specificity of ~58%.(36630775)

complications & risk

- Both procedures carry risks of IPF exacerbation, pneumothorax +/- persistent air leak, and hemorrhage.

- Surgical lung biopsy carries additional risks including delayed wound healing and persistent neuropathic pain.

- Cryobiopsy may carry a higher risk of endobronchial bleeding, since tissue is removed from within the bronchus.

- Direct comparison of risks is difficult to ascertain. However, overall it is likely that cryobiopsy is safer than surgical biopsy.

histopathology of UIP (usual interstitial pneumonia)

hallmark histological features of UIP (usual interstitial pneumonia)

- Geographic and temporal heterogeneity:

- Geographic heterogeneity: patches of diseased lung may abut patches of normal lung.

- Temporal heterogeneity: some lung is fibrotic, whereas other lung shows signs of fibroblastic foci and active inflammation.

- Subpleural accentuation.

- Numerous fibroblastic foci.

- Significant honeycomb change.

- Interstitial inflammation is commonly seen, but it is typically mild and patchy.(Walker 2019)

classification of biopsy findings

- Similar to CT findings, the overall constellation of histological findings may be classified into four categories:

- Definite UIP pattern:

- (1) Patchy dense fibrosis with architectural distortion (i.e., destructive scarring and/or honeycombing).

- (2) Predilection for subpleural and paraseptal lung parenchyma.

- (3) Fibroblastic foci.

- (4) Absence of features that suggest an alternative diagnosis (red text below). (35486072)

- Probable UIP pattern:

- Evidence of marked fibrosis/architectural distortion +/- honeycombing.

- Absence of either patchy involvement or fibroblastic foci (but not both).

- Either one of the following:

- Absence of six features inconsistent with UIP (red text below).

- -OR-

- Honeycomb changes only.

- Possible UIP pattern:

- Patchy or diffuse involvement of lung parenchyma by fibrosis, with or without interstitial inflammation.

- Absence of other criteria for UIP (see green text above).

- Absence of six features inconsistent with UIP (see red text below).

- Not UIP pattern if any of these features are present:

- (1) Hyaline membranes.

- (2) Organized pneumonia.

- (3) Granulomas.

- (4) Marked interstitial inflammatory cell infiltrate away from honeycombing.

- (5) Predominant airway centered changes.

- (6) Other features suggestive of an alternate diagnosis.

(#1) other causes of UIP (these are the closest mimics of IPF)

- Pneumoconiosis (primarily asbestosis).

- Connective tissue-associated ILD (especially rheumatoid arthritis; table below).

- Drug-induced lung diseases.

- HP (hypersensitivity pneumonitis) may rarely cause a UIP pattern on CT scan. (36630775)

(#2) other common differential considerations

- NSIP (nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis).

- Chronic aspiration.

- Fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis.

- Recovery from ARDS, with subsequent pulmonary fibrosis.

The diagnostic process will vary between patients, depending on individual characteristics and patient preferences. A diagnosis of IPF includes the following components:

- (1) Exclusion of alternative causes of fibrotic interstitial lung disease (see the section on differential diagnosis above).

- (2) Some combination of CT scan +/- histopathology which supports the diagnosis of IPF (see figure below).

- For younger patients, definite diagnosis may be more important (e.g., to support candidacy for lung transplantation). Consequently, pursuing a tissue diagnosis may be worth the risk involved.

- For older and/or multimorbid patients, empiric therapy based on a working diagnosis of IPF may be safer than pursuing a tissue diagnosis.

provisional working diagnosis of IPF

- A provisional working diagnosis of IPF may often be reached in the absence of a biopsy. This is clinically reasonable if: (36630775, 36702498)

- The likelihood of IPF is ~60-90%.

- Other more treatable diseases have been reasonably excluded.

- A biopsy proving IPF wouldn't affect management.

- Treatment may include supportive care and anti-fibrotic therapies.

- Serial follow-up over time may confirm or refute the diagnosis of IPF: (36630775)

- Progressive fibrosis with a CT scan that is more typical of IPF may confirm the diagnosis.

- Resolution over time would refute the diagnosis of IPF.

(The following discussion explores treatment of stable disease; for a discussion of the treatment of an IPF exacerbation, see this chapter: 📖)

treatment basics

- Antifibrotic therapy may be the most important intervention (as discussed further below).

- Oxygen therapy: Indications for oxygen appear to be similar to those for patients with COPD, as discussed further here: 📖

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease should be treated aggressively if it is present, but evidence supporting acid suppression in IPF is mixed. Guidelines do not recommend treating all patients with IPF with acid suppressive medication. (35486072)

- Other lung-supportive measures:

- Pulmonary rehabilitation.

- Smoking cessation. 📖

- Appropriate vaccinations.

- 🛑 Immunosuppressive therapy hasn't been shown to be helpful. For patients with definite IPF, steroids should generally be avoided outside of an IPF exacerbation.

- The PANTHER trial of prednisolone, azathioprine and N-acetylcysteine found that these therapies were harmful.(22607134)

Overall, the efficacy of pirfenidone versus nintedanib seem to be similar. Choice of agent may relate to logistic issues (e.g., drug interactions, contraindications).

pirfenidone

basics

- Oral agent with anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic properties. Pirfenidone appears to reduce fibroblast proliferation via an unclear mechanism. (Fishman 2023)

indication & evidence

- IPF:

- Therapy should be started following IPF diagnosis. (36630775)

- Pirfenidone decreases the rate of FVC (forced vital capacity) decline over a year by ~50%.

- In a combined analysis of the ASCEND and CAPACITY trials, pirfenidone was associated with a decrease in mortality.(26647432)

- A prospective observational study found that pirfenidone may improve cough by ~30%.(36630775)

contraindications:

- Child-Pugh class C cirrhosis.

- Severe renal failure (GFR < 30 ml/min).

- Surgery: Discontinuation before and up to three weeks after surgery might improve wound healing.(36630775)

pharmacology

- 801 mg PO TID with food. It may be initiated gradually (267 mg TID for a week, then 534 mg TID, then 801 mg TID). (37055085)

- Interactions:

- Inhibitor of CYP-1A2.

- Inducer of CYP-1A2.

side effects

- Photosensitive rash (may be avoided with use of sunscreen).

- GI events (anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea).

- Weight loss.

- Insomnia.

- DILI (drug-induced liver injury) – liver function tests need to be monitored. This seems to be the only potentially serious adverse event.

nintedanib

basics

- Oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor that antagonizes receptors for platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and fibroblast growth factor.

indications & evidence

- IPF:

contraindications

- Patients at high risk of bleeding were excluded from INPULSIS 1-2 trials (e.g., anticoagulant therapy, dual antiplatelet therapy, history of hemorrhage).

- Ischemic heart disease (recent history of myocardial infarction or unstable angina).

- Cirrhosis, Child-Pugh class B or C.

- Renal failure with GFR <30 ml/min.

- Surgery: Discontinuation before and up to three weeks after surgery might improve wound healing.(36630775)

- Pregnancy. (37055085)

pharmacology

- Dose: 150 mg PO BID, taken with food.

- Interactions:

- P-glycoprotein inhibitors (e.g., ketoconazole, erythromycin, cyclosporine).

- P-glycoprotein inducers (e.g., rifampin, carbamazepine, phenytoin).

- Pirfenidone.

side effects

- Gastrointestinal side effects are most common (diarrhea in most patients; nausea; vomiting).

- Weight loss.

- Bleeding risk; anticoagulants should be avoided. (ERS handbook 3rd ed.)

- Photosensitive rash.

- Transaminitis (liver function tests require monitoring).

epidemiology of precapillary pulmonary hypertension in IPF

- Some patients may develop pulmonary hypertension despite well-preserved lung function, whereas other patients develop pulmonary hypertension in the context of significant hypoxemia (disproportionate pulmonary hypertension).

- Overall rates: (36630775)

- At diagnosis, ~10% of patients have pulmonary hypertension.

- When undergoing lung transplant evaluation, ~30% of patients have pulmonary hypertension.

evaluation

- Patients with known IPF should still receive an evaluation for other causes of pulmonary hypertension (e.g., obstructive sleep apnea, thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension).

- Evaluation of patients with pulmonary hypertension is described here: 📖

management

- The most important therapy is supplemental oxygen.

- Other therapies which could be considered include:

- Diuretic treatment to establish euvolemia.

- Inhaled treprostinil.(33440084)

- Further discussion of the management of pulmonary hypertension due to lung disease: 📖

disease course

- Disease course is variable, for example:

- Some patients' disease may rapidly and inexorably progress.

- Some patients may have periods of stability, punctuated by rapid deterioration due to acute exacerbations (stars in the figure below).

- Among patients with mild-moderate impairment in lung function, FVC decreases an average of ~150-200 ml/year.(36702498)

median survival

- Median survival following diagnosis is 3-5 years. However, patients are usually diagnosed several years after the true onset of the disease. For patients who are incidentally diagnosed radiographically, median survival will be longer.

- The GAP model may be used to prognosticate based on gender, age, and physiology. 🧮

adverse prognostic factors

- Demographic factors:

- Older age.

- Male sex.

- Initial signs and symptoms:

- BMI (body mass index) < 25 kg/m2.

- Dyspnea intensity.

- Impaired PFTs:

- DLCO <~35-40% predicted.

- FVC <60% predicted.

- Desaturation to <88% during six-minute walk test.

- Substantial honeycombing on the chest CT scan.

- Mediastinal lymphadenopathy (>10 mm).

- Precapillary pulmonary hypertension.

- Signs and symptoms appearing during follow-up:

- Weight loss >5% of body weight.

- Worsening dyspnea.

- Worsening PFTs (e.g., 10% reduction in FVC or 15% reduction in DLCO within six months).(Fishman 2023)

- Dependence on higher amounts of supplemental oxygen.

- Decrease in six-minute walk time distance by >50 meters.

- Worsening fibrosis on chest CT scan.

- Development/worsening of pulmonary hypertension; decompensated cor pulmonale.

- Acute exacerbation of IPF. (36630775)

basics

- Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema (CPFE) is defined by a combination of upper lobe emphysema plus lower lobe pulmonary fibrosis.

- Most cases involve a combination of emphysema plus IPF. About a third of IPF patients also have emphysema (both disorders may be linked to smoking).

- CPFE is not precisely defined. For example, the severity of pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema required to make this diagnosis is unclear. (Walker 2019)

- CPFE also encompasses the combination of emphysema with other fibrotic lung disease (e.g., connective tissue-related interstitial lung disease).(33965153)

- CPFE is highly debilitating because both the upper and the lower lung fields are damaged, often leaving little residual lung tissue.

epidemiology

- ~98% of patients with CPFE have a history of smoking.(33965153)

- There is a 9:1 ratio of men:women.(33965153)

- The mean age of diagnosis is ~60-70 years old (slightly older compared to IPF).(33965153, Walker 2019)

pulmonary function tests

- Spirometry may be relatively unremarkable, due to the opposing effects of pulmonary fibrosis (restriction) and emphysema (obstruction).

- Typical findings on pulmonary function testing:

- Near normal TLC, FEV1, and FVC.

- Normal or slightly reduced FEV1/FVC.

- Markedly reduced DLCO (since both emphysema and pulmonary fibrosis will decrease the DLCO).

- ⚠️ FVC (forced vital capacity) cannot be followed as an indicator of the severity of interstitial lung disease.

radiology

- Core findings:

- Upper lobes may demonstrate centrilobular and/or paraseptal emphysema.

- Lung bases show fibrosis.

- Other findings which may be seen:

- Concomitant respiratory bronchiolitis (RB-ILD) or desquamative interstitial pneumonitis (DIP) may cause ground glass opacities.

- Evidence of pulmonary hypertension is often present.

diagnostic evaluation

- A characteristic CT scan in a patient with significant tobacco history is highly suggestive of CPFE.

- However, investigation should evaluate the possibility of another process leading to pulmonary fibrosis (e.g., connective tissue-related interstitial lung disease).

management

- Treatment involves a combination of therapy for emphysema and therapy for pulmonary fibrosis.

- Patients are at increased risk of pulmonary hypertension.

- Patients are at very high risk of lung cancer. Unfortunately, the presence of pulmonary fibrosis renders many therapies difficult or impossible to tolerate (e.g., lung resection may be impossible; chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy carry a risk of causing an exacerbation of interstitial lung disease).(33965153)

- Smoking cessation is especially important.

basics

- Short telomere syndromes are a collection of rare genetic disorders that involve premature shortening of telomeres, which causes premature aging of various organs.

- Consider the diagnosis in patients with IPF <50 years old.

epidemiology

- Might account for ~15% of IPF.

- May cause patients to present with IPF at an unusually young age.

- Family history: Some forms have autosomal dominant transmission.

non-pulmonary clinical features

- Integument:

- Premature graying (<30 years old).

- Skin reticular pigmentation.

- Nail dystrophy.

- Oral mucosal leukoplakia.

- Myelodysplastic bone marrow failure:

- Thrombocytopenia, macrocytosis.

- Aplastic anemia.

- Acute leukemia.

- Cirrhosis.

- Radiation sensitivity.

- Sensitivity to certain immunosuppressive agents.

- Infertility.

diagnostic testing

- Telomere length of peripheral blood can be tested. Length below the tenth percentile for age supports a diagnosis of short telomere syndrome. Evaluating telomere length has the advantage that this test should be relatively robust regardless of whether the underlying genetic mutation is known. (33258668)

- Genetic panels may evaluate for underlying mutations.

management

- IPF is managed similarly to idiopathic IPF.

- General supportive care:

- Liver function testing should be considered to evaluate for cirrhosis.

- Bone-marrow suppressive medications are contraindicated.

- Short telomere syndromes may produce problems with lung transplantation:

- Genetic counseling may be considered for family members.

concept of progressive pulmonary fibrosis (PPF)

- PPF refers to patient with ILD of known or unknown etiology other than IPF, with evidence of progressive fibrosis.

- The following figure illustrates which diseases are most likely to cause PPF:

definition of progressive pulmonary fibrosis

- At least two of the following three criteria must have occurred within the past year, with no alternative explanation:

- (1) Worsening respiratory symptoms.

- (2) Physiological evidence of disease progression (either of the following):

- FVC decline >5% predicted within one year of follow-up.

- DLCO decline >10% predicted within one year of follow-up (corrected for hemoglobin).

- (3) Radiological evidence of disease progression (one or more of the following):

- Increased extent or severity of traction bronchiectasis and bronchiolectasis.

- New ground-glass opacity with traction bronchiectasis.

- New fine reticulation.

- Increased extent or increased coarseness of reticular abnormality.

- New or increased honeycombing.

- Increased lobar volume loss.

management

- Treatment will obviously vary, depending on the specific lung disease.

- Antifibrotic therapy:

- Nintedanib is recommended for patients with progressive fibrosis despite standard disease-specific management. (35486072) This recommendation is based largely on the INBUILD trial.

- Pirfenidone also appears to be effective for PPF. Evidence is less robust, but this has been supported by RCT-level evidence.(33798455, 37055085, 31578169)

To keep this page small and fast, questions & discussion about this post can be found on another page here.

Guide to emoji hyperlinks

= Link to online calculator.

= Link to Medscape monograph about a drug.

= Link to IBCC section about a drug.

= Link to IBCC section covering that topic.

= Link to FOAMed site with related information.

- 📄 = Link to open-access journal article.

= Link to supplemental media.

References

- 33258668 Lyons MI, Homsy E, Allen JN. Pulmonary Fibrosis Uncovered during Evaluation for Orthotopic Liver Transplantation. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020 Dec;17(12):1629-1632. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202003-248CC [PubMed]

- 33965153 Chong WH, Saha B, Shkolnik B. Persistent Dyspnea in a 74-Year-Old Man With Normal Spirometry and Lung Volumes. Chest. 2021 May;159(5):e303-e307. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.10.052 [PubMed]

- 35486072 Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, Thomson CC, Inoue Y, Johkoh T, Kreuter M, Lynch DA, Maher TM, Martinez FJ, Molina-Molina M, Myers JL, Nicholson AG, Ryerson CJ, Strek ME, Troy LK, Wijsenbeek M, Mammen MJ, Hossain T, Bissell BD, Herman DD, Hon SM, Kheir F, Khor YH, Macrea M, Antoniou KM, Bouros D, Buendia-Roldan I, Caro F, Crestani B, Ho L, Morisset J, Olson AL, Podolanczuk A, Poletti V, Selman M, Ewing T, Jones S, Knight SL, Ghazipura M, Wilson KC. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (an Update) and Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis in Adults: An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022 May 1;205(9):e18-e47. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202202-0399ST [PubMed]

- 36630775 Cottin V, Bonniaud P, Cadranel J, Crestani B, Jouneau S, Marchand-Adam S, Nunes H, Wémeau-Stervinou L, Bergot E, Blanchard E, Borie R, Bourdin A, Chenivesse C, Clément A, Gomez E, Gondouin A, Hirschi S, Lebargy F, Marquette CH, Montani D, Prévot G, Quetant S, Reynaud-Gaubert M, Salaun M, Sanchez O, Trumbic B, Berkani K, Brillet PY, Campana M, Chalabreysse L, Chatté G, Debieuvre D, Ferretti G, Fourrier JM, Just N, Kambouchner M, Legrand B, Le Guillou F, Lhuillier JP, Mehdaoui A, Naccache JM, Paganon C, Rémy-Jardin M, Si-Mohamed S, Terrioux P; OrphaLung network. French practical guidelines for the diagnosis and management of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis – 2021 update. Full-length version. Respir Med Res. 2023 Jun;83:100948. doi: 10.1016/j.resmer.2022.100948 [PubMed]

- 36702498 Podolanczuk AJ, Thomson CC, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, Martinez FJ, Kolb M, Raghu G. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: state of the art for 2023. Eur Respir J. 2023 Apr 20;61(4):2200957. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00957-2022 [PubMed]

- 37055085 Strykowski R, Adegunsoye A. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis and Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2023 May;43(2):209-228. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2023.01.010 [PubMed]

Books:

- Shah, P. L., Herth, F. J., Lee, G., & Criner, G. J. (2018). Essentials of Clinical pulmonology. In CRC Press eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315113807

- Shepard, JO. (2019). Thoracic Imaging The Requisites (Requisites in Radiology) (3rd ed.). Elsevier.

- Walker C & Chung JH (2019). Muller’s Imaging of the Chest: Expert Radiology Series. Elsevier.

- Palange, P., & Rohde, G. (2019). ERS Handbook of Respiratory Medicine. European Respiratory Society.

- Murray & Nadel: Broaddus, V. C., Ernst, J. D., MD, King, T. E., Jr, Lazarus, S. C., Sarmiento, K. F., Schnapp, L. M., Stapleton, R. D., & Gotway, M. B. (2021). Murray & Nadel’s Textbook of Respiratory Medicine, 2-Volume set. Elsevier.

- Fishman's: Grippi, M., Antin-Ozerkis, D. E., Cruz, C. D. S., Kotloff, R., Kotton, C. N., & Pack, A. (2023). Fishman’s Pulmonary Diseases and Disorders, Sixth Edition (6th ed.). McGraw Hill / Medical.