CONTENTS

CONTENTS

- Basics – what is HLH?

- Clinical features of HLH

- Laboratory findings

- Pathology – Hemophagocytosis

- Causes of HLH

- Differential diagnosis – Closest mimics of HLH

- Approach to the diagnosis of HLH

- Treatment

- Podcast

- Questions & discussion

- Pitfalls

what is HLH?

what is HLH?

- HLH is a state of pathological immune hyperactivity involving CD8+ T-cells and macrophages as shown above. This involves a number of positive feed-back loops, which can cause inflammation to rapidly spiral out of control.

- There are roughly two factors involved in the development of HLH:

- (#1) An individual's tendency to develop HLH. Normally, HLH is prevented by feed-back mechanisms which put a brake on inflammation. Rare individuals have various mutations in these mechanisms, creating a tendency to develop HLH.

- (#2) Inflammatory triggers will tend to push patients into HLH. The more intense and chronic the inflammatory trigger is, the harder it is for the body's immune system to maintain equilibrium. Chronic viral infections, malignancy, or rheumatologic disease seem to be particularly strong triggers of HLH.

- Pediatric HLH is most often due largely to genetic factors which lead to a tendency to develop HLH (#1). In adults, genetic abnormalities tend to be less important, with inflammatory triggers playing a greater role (#2 above). However, it is often difficult to sort this out precisely. Thus, the differentiation between “primary” and “secondary” HLH is falling out of vogue (because many patients who appear to have “secondary” HLH may actually have some underlying genetic mutations if you look carefully enough).(30766533)

- Some immunodeficiency syndromes or immunosuppressive agents may be associated with the development of HLH. The underlying mechanism may be that immunosuppression leads to chronic, persistent infection that then serves as a trigger for HLH.

what is hemophagocytosis?

- Hemophagocytosis is when macrophages eat blood cells (including erythrocytes, leukocytes, or platelets).

- This seems to reflect excessive inflammatory activation of macrophages.

- Hemophagocytosis is a histological hallmark of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. However, this isn't particularly sensitive (so patients can have HLH without having tissue evidence of hemophagocytosis).

terminology: HLH vs. MAS

- HLH is a broad term which encompasses immune dysregulation due to a wide variety of stimuli.

- Macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) refers to HLH caused by rheumatologic disease. As such, macrophage activation syndrome is one subset of HLH.

fever

- Generally quite sensitive (e.g., ~95%). However, in the ICU this may be somewhat less sensitive due to the use of antipyretics, continuous renal replacement therapy, or ECMO.(30992265)

- Often lasting weeks prior to ICU admission.

CNS HLH (~25-50%)

- Symptoms may vary widely:(34950412)

- Subtle delirium ranging in severity to coma.

- Focal neurologic deficits (e.g., ataxia, dysarthria, cranial nerve palsies).

- Headaches, meningismus.

- Seizure.

- PRES (posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome).

- Most patients have neurologic features in the context of systemic findings, but some patients can have isolated neurologic symptoms.(34950412)

- CSF findings are discussed below: 📖

- Neuroimaging may vary widely, including:(34950412)

- Multifocal white matter demyelination-like changes.

- Large, ill-defined confluent lesions.

- CNS hemorrhage, or microhemorrhages within lesions.

- Leptomeningeal enhancement.

shock, multi-organ failure

- Shock may involve capillary leak and/or myocarditis.

- ARDS, AKI may occur.

organomegaly

- Splenomegaly in ~70% of patients (30384814)

- Hepatomegaly

- Lymphadenopathy isn't associated with HLH. If present, substantial lymphadenopathy should raise a concern for another underlying disease process (e.g., lymphoma, Castleman disease, histoplasmosis, or tuberculosis).(31339233)

CBC

- All cell lines may be affected (thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, anemia).

- In some patients with secondary HLH, patients may begin with baseline leukocytosis and/or thrombocytosis and these counts may subsequently fall as HLH emerges.

liver function tests

- Elevated aminotransferase levels can occur early and often track with disease activity.(32387063) Fulminant liver failure and marked elevation of transaminases can occur.

- Abnormality is sensitive for HLH, but not at all specific.

- Bilirubin elevation is common.

- Hypertriglyceridemia

- Late reflection of severe liver involvement.

- The test performance of hypertriglyceridemia among critically ill patients with little nutritional intake is unclear (as fasting may reduce the triglyceride level).

coagulation abnormalities

- Activated macrophages appear to trigger fibrinolysis (possibly by secreting ferritin or plasminogen).((32387063, 30384814) This leads to a hemorrhagic form of disseminated intravascular coagulation with hyperfibrinolysis and low fibrinogen levels.

- Elevated D-dimer

- Prolonged INR and PTT

inflammatory markers

- Ferritin is invariably elevated >500 ng/ml, and generally much higher (e.g., >2,000 ng/ml).

- More discussion of hyperferritinemia below (REF LINK).

- Soluble IL-2 receptor (CD25) is markedly elevated (functioning as a marker of T-cell activation). Unfortunately, this is generally a send-out test with a slow turnaround time.

- C-reactive protein and procalcitonin are typically elevated.(28477737)

- Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) is initially elevated, but as fibrinogen levels fall the ESR will fall as well.

ferritin

- Regulated by: iron levels, cytokines (especially IL-6)(23965472)

- Acute phase reactant which increases with induction by TNF-alpha and IL-1a.(25851400)

- Normal range in adults is ~20-300 ng/mL.

- Secreted by splenic macrophages and proximal tubule cells of the kidney.

interpretation of ferritin elevation

- A ferritin level >500 ng/ml is used as a criterion for HLH diagnosis, but this is derived from pediatric studies. Adult HLH patients typically have much higher ferritin levels (e.g., above ~2,000 ng/mL). More extreme elevations of ferritin are a bit more specific for HLH. However, there are many other causes of severely elevated ferritin (listed below). Therefore, extreme hyperferritinemia alone doesn't necessarily indicate a diagnosis of HLH.

- Rapidly rising ferritin levels may be more consistent with evolving HLH.

causes of markedly elevated ferritin

- Erythrocyte disorders:

- Hemolysis.

- Iron overload due to multiple transfusions.

- Renal failure (especially hemodialysis).

- Liver disease:

- Cirrhosis.

- Acute hepatitis (e.g., viral, ischemic, or alcoholic).

- Acetaminophen overdose.

- Hemochromatosis.

- Inflammatory states:

- Malignancy (hematologic >> solid tumor).

- Infection (especially infections that are capable of causing HLH). 📖

- Graft Versus Host Disease (GVHD).

- Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.

- Rheumatologic disorder (especially adult onset Still's Disease).

- HLH (often secondary to one of the above triggers).

- References: 23965472, 25851400, 27247369, 28762079, 31991015, 31995958

caution & contraindications

- HLH causes a hemorrhagic form of DIC which may increase the risk of bleeding (due to reduced fibrinogen levels, hyperfibrinolysis, and thrombocytopenia).

- Consider checking fibrinogen, coagulation studies, and CBC prior to lumbar puncture.

findings

- (1) Basic chemistry findings

- Elevated protein levels

- Lymphocytic pleocytosis (make sure)

- This is nonspecific.

- (2) Cytology for hemophagocytosis

- Uncommon, but you may get lucky.(27292929)

- Searching for hemophagocytosis itself isn't an adequate indication for lumbar puncture.

- (3) Excluding alternative etiologies

- Practically speaking, the greatest utility of lumbar puncture is exclusion of alternative etiologies (e.g., bacterial meningitis, HSV or VZV encephalitis).

basics of hemophagocytosis

- Macrophages are phagocytosing erythrocytes, platelets, or leukocytes.

- Essentially this serves as histopathological evidence supporting macrophage dysregulation.

- May be seen in various tissues. Most commonly sampled tissues include the bone marrow, lymph nodes, or liver. Source of the biopsy may depend on which organs are involved (e.g., bone marrow biopsy may be most appropriate for a patient with cytopenias, whereas liver biopsy may be more appropriate for a patient with marked liver abnormalities). Optimal site of biopsy may also be constrained by coagulopathies (e.g., a bone marrow biopsy may be safer than a liver biopsy in the context of coagulopathy).

diagnostic performance:

- (1) Not sensitive

- Often absent initially.

- Sensitivity may be in the range of 50%.

- A repeat biopsy later in the disease course may reveal hemophagocytosis.

- (2) Not specific

- Can be seen in infections, blood transfusions, autoimmune disease.(32387063)

The differential will vary depending on each specific patient's presentation. The following entities may mimic HLH closely:

- Liver disease

- Catastrophic Antiphospholipid Antibody Syndrome (CAPS)

- Sepsis / septic shock (especially culture-negative septic shock)

- Drug Rash with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS)(31339233)

HLH associated with rheumatic conditions (Rh-HLH, also called macrophage activating syndrome)

- More often:

- SLE

- Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (a.k.a., systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis)

- Adult onset Still's disease

- Less often:

- Rheumatoid arthritis, mixed connective tissue disorder, scleroderma, Sjogren's syndrome, dermatomyositis

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Kawasaki disease

HLH associated with malignancy (M-HLH)

- ~90% hematologic malignancies

- Especially NK-cell or T-cell leukemia or lymphoma.

- Solid tumors (including teratoma, breast cancer)

HLH due to immune-activating therapies or drug hypersensitivity (Rx-HLH)

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors (e.g., nivolumab, ipilimumab)

- Genetically engineered CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, as a component of CAR-T cell therapy

- Some drugs (e.g., lamotrigine)

HLH due to infection (most often viruses or intracellular pathogens)

- Viruses:

- Herpes viruses, especially EBV (also CMV, HSV, VZV).

- Disseminated adenovirus.

- RSV.

- Influenza (especially H1N1), COVID-19.

- Parvovirus B19.

- Chronic viruses (HIV, HBV, HCV).

- Bacterial infections

- Ehrlichia, Bartonella, Brucella.

- Tuberculosis.

- Legionella.

- Anaplasmosis, babesiosis.

- Fungal infections:

- PJP.

- Histoplasma.

- Parasites (e.g., Leishmania, Plasmodium, Toxoplasma).

HLH with immune compromise (IC-HLH)

- HIV

- Immunosuppressive medications

- Transplantation (may accompany EBV lymphoproliferative disorder)

- Various congenital immunodeficiencies (typically pediatric onset)

familial HLH (F-HLH)

- Patients with a strong genetic inclination to develop HLH may develop HLH spontaneously (without any discernible trigger).

- This occurs predominantly in children.

The general definition of HLH is below. Unfortunately, critically ill patients may not meet these criteria fully until they are moribund. Diagnosis is ultimately a matter of clinical judgement, with careful consideration of the clinical context and competing diagnoses. Different criteria have been designed to identify HLH within the context of known SLE or systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis.(27292929)

- The traditional definition of HLH is based upon the HLH-2004 criteria shown above. HLH-2004 criteria are unhelpful in critically ill adults for several reasons:(28631531)

- 1) These criteria were developed for use in a clinical trial of pediatric HLH. They haven't been validated in adult HLH.

- 2) They rely on tests which are impossible to obtain rapidly (or ever).

- 3) By the time HLH-2004 criteria are officially “positive” the patient may be moribund and beyond the point of optimal intervention. Consequently, some clinicians are moving past rigid criteria, with initiation of therapy before traditional diagnostic criteria are met.(28871523)

- The modified 2009 criteria listed above are more sensitive, but less specific. They may be more helpful clinically, in terms of detecting HLH early. However, it must be understood that merely satisfying these criteria doesn't guarantee a diagnosis of HLH – clinical context and competing diagnoses must also be considered.

- Determining the H-score might be a preferable approach.(30075527) This is easily obtained using an online calculator at MDCalc. The optimal cutoff value is unclear (with potential cutoffs ranging between 138-169).(27298397)

core diagnostic elements to consider when initially determining whether an ICU patient might have HLH

- Underlying cause & pre-test probability

- A higher index of suspicion is appropriate in patients known to have a disorder which can trigger HLH.

- Examples include: rheumatologic diseases, hematologic malignancy, and specific infections (additional causes above)(REF)

- Competing diagnoses

- Are there alternative diagnoses which can explain the clinical findings?

- Close mimics of HLH include liver disease, septic shock, and catastrophic antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (CAPS).

- Fever

- Present in the vast majority of patients with HLH.

- The diagnosis of HLH should be questioned in the absence of a fever.

- Liver function test abnormality

- Present in vast majority of patients with HLH.

- Nonspecific, but the diagnosis should be questioned if liver function tests are normal.

- Ferritin

- Hyperferritinemia is a requisite for diagnosis of HLH in adults.

- Generally >>1,000 ug/L (values of >6,000-10,000 ug/L are somewhat more specific, but less sensitive.)

- Cytopenias

- Extremely common in HLH.

- Lack of cytopenias casts doubt on the diagnosis of HLH (31339233)

- Splenomegaly or hepatosplenomegaly

- Splenomegaly isn't always present.

- If present, these may help favor a diagnosis of HLH over sepsis. However, hepatosplenomegaly won't necessarily differentiate HLH versus liver disease.

studies to obtain when investigating for possible HLH

- Basic panel

- CBC

- Ferritin

- Liver function tests

- Fibrinogen

- Triglyceride level (fasting)

- Additional considerations:

- soluble IL-2 receptor (a.k.a. sCD25)

- INR, PTT, D-dimer

- Blood PCR for herpes viruses (especially EBV, CMV, and HSV)

- Ultrasound of liver & spleen

- Lumbar puncture and/or MRI if possible if suspicion of brain involvement

- Biopsy of involved sites (especially bone marrow)

studies to consider when investigating for the etiology of HLH

- CT chest/abdomen/pelvis (evaluation for malignancy or occult infection)

- HIV serology

- Antinuclear antibody (ANA)

- Serum PCR for EBV, CMV, HSV, VZV

- Serum 1,3-beta-D-glucan level

- Evaluation for additional potential infections, depending on exposure history (may include anaplasmosis, babesiosis, PJP, histoplasmosis, parasitic infections, other chronic viral infections). A more complete list of possible infectious triggers is listed above.

- Perhaps the most essential intervention for these patients is identification and treatment of the underlying cause of the HLH.

- The underlying disease should be aggressively treated if possible. For example:

- Malignancy: combination chemotherapy may be needed.

- Infection: appropriate antimicrobial therapy. Rituximab may reduce viral load and improve EBV-associated HLH.(27292929)

- Rheumatologic disease flare: Management may require pulse-dose steroid or augmented immunosuppressive regimens (more on this below).

mainstay of therapy for HLH

- Steroid is the most broadly utilized therapy for HLH.(21366922, 20348529) Most treatment regimens involve some dose of steroid.

- In the absence of definitive evidence, steroid doses vary widely.

- Dexamethasone may have an advantage with regard to superior CNS penetration.

moderate dose steroid

- A moderate dose of steroid may consist of dexamethasone 10 mg/m2 body surface area daily (~15-20 mg daily).

- This steroid dose by itself could be adequate for early or impending HLH, but not fulminant HLH.

- For more severe HLH, a moderate-dose steroid may be combined with a second therapy (e.g., anakinra or ruxolitinib).(16937360)

pulse-dose steroid

- This is often used in patients with HLH due to rheumatologic disease (a.k.a. macrophage activating syndrome). A typical regimen is pulse-dose IV methylprednisolone (1000 mg/day for three days) followed by lower doses of steroid (e.g., ~2-3 mg/kg/day).(32387063)

- Some case reports describe success with pulse-dose steroid in HLH due to influenza H1N1 (e.g., 500-1000 mg methylprednisolone daily for three days).(17106167, 22286408)

- Advantages include that this is inexpensive, readily available, and has a tolerable side-effect profile (particularly at 125 mg IV q6hr, a dose commonly used for obstructive lung disease).

- Drawbacks include an increased risk of invasive fungal infection at very high doses of steroid (e.g., Aspergillus).

basics

- Anakinra is a fairly safe agent which reduces inflammation via inhibition of IL-1 receptors. Some studies in pediatric and adult HLH suggest that it may be effective. (26154908, 24583503, 26584195)

- One main limitation of anakinra is availability and cost. Efficacy appears to require a fairly large dose of anakinra (e.g., perhaps roughly 4-10 mg/kg total daily dose), which can be challenging to provide. (28631531)

- Providing an anakinra dose designed for outpatients with rheumatoid arthritis (e.g., 100 mg s.c. daily) may be inadequate.

use in infection-triggered HLH

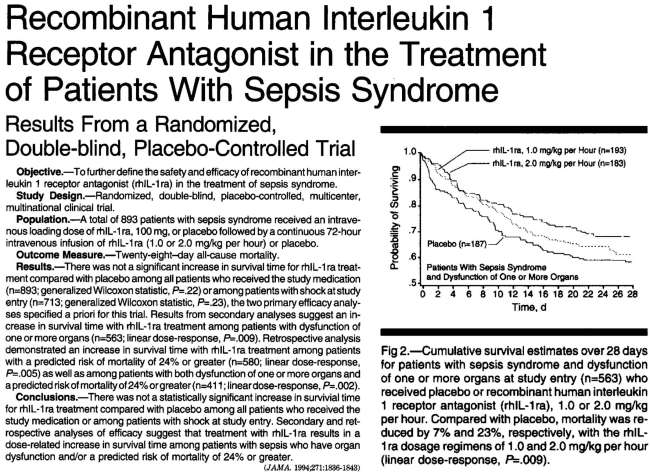

- One Phase-III RCT of anakinra in septic shock failed to show benefit.(8196140) However, mortality was improved among subsets of patients with organ failure (figure below). Furthermore, a retrospective re-analysis of the study also found mortality benefit among a subset of patients with features of HLH.(26584195) The dose of anakinra utilized in the study was 100 mg IV bolus followed by 1-2 mg/kg/hour infusion over 72 hours.

- One retrospective study with COVID-19 found that 100 mg s.c. BID was unable to affect inflammatory markers, but 5 mg/kg IV BID might be beneficial.(32470486)

use in HLH due to rheumatologic disease

- Anakinra might to be effective in HLH due to rheumatologic disorders, where it may be used at high doses (e.g., 4-10 mg/kg/day in divided doses).(30992265, 32387063).

ruxolitinib

- Ruxolitinib is a small molecule inhibitors of Janus kinases (JAK1 and JAK2) – which are involved in numerous cytokine signaling pathways (including signaling from interferon-gamma, IL-6, IL-2, and IL-12). Activity at multiple sites could make this more effective than agents which act on a single cytokine.

- Typical use is as an outpatient maintenance therapy for myelodysplastic syndrome, but ruxolitinib is being repurposed as an anti-inflammatory agent. For example, it may be used for steroid-refractory graft versus host disease.

- Ruxolitinib overall seems fairly safe (for example, it is used on a chronic basis for fragile outpatients with myelodysplastic syndrome). It may increase the risk of some chronic viral infections (e.g., HBV) and tuberculosis. Ruxolitinib causes a transient impairment in cytokine function, but it could theoretically be rapidly weaned or discontinued if a worsening nosocomial infection were to develop.

- Case series suggest efficacy of ruxolitinib in HLH:

- An open-label pilot study reported success using 15 mg BID in five patients with secondary HLH.(31537486)

- Wang et al. utilized ruxolitinib for salvage therapy of 34 patients with refractory or relapsed HLH. Complete remission was achieved in 15% of patients and partial remission in 59%.(31515353)

- Cases describe the use of ruxolitinib in patients with HLH due to HIV-related EBV and due to histoplasmosis.(32285358, 29417621) This suggests that ruxolitinib might be safe in patients who have an active infection.

- Traditionally, HLH has been treated with chemotherapeutic regimens (e.g., the HLH-2004 protocol involving etoposide and cyclosporine). However, these therapies were designed for children with congenital HLH due to deficiencies in natural killer cell function.

- In adults with HLH triggered by a specific disorder, the role of etoposide is unclear. It does seem to work. The question is whether anakinra or ruxolitinib may provide similar efficacy with less toxicity.

- Potential complications from etoposide include myelosuppression, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES), and delayed development of secondary leukemia.

- Based on the toxicity profile of etoposide, its use requires a greater degree of confidence in the diagnosis of HLH. Alternatively, it may be reasonable to start other therapies (e.g., steroid and ruxolitinib) earlier in the disease course when there is a greater degree of diagnostic uncertainty.

Follow us on iTunes

The Podcast Episode

Want to Download the Episode?

Right Click Here and Choose Save-As

To keep this page small and fast, questions & discussion about this post can be found on another page here.

- Failure to consider HLH as a possible differential diagnosis in a patient labeled with “sepsis” who isn't responding to therapy.

- Failure to thoroughly search for underlying triggers of HLH, after the diagnosis of HLH has been made.

- Delaying treatment for HLH until the patient has met formal 2004 criteria for HLH.

- Assumption that a profoundly elevated ferritin proves the diagnosis of HLH.

Guide to emoji hyperlinks

= Link to online calculator.

= Link to Medscape monograph about a drug.

= Link to IBCC section about a drug.

= Link to IBCC section covering that topic.

= Link to FOAMed site with related information.

= Link to supplemental media.

Going further

- Sepsis 4.0 – Understanding sepsis/HLH overlap syndrome (PulmCrit)

- HLH: A Critical Care Conundrum (Maryland CCC project, by Jennie Y. Law)

- Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (HLH): A Zebra Diagnosis We Should All Know (RebelCrit, by Sandra K. Baril)

References

- 08196140 Fisher CJ Jr, Dhainaut JF, Opal SM, et al. Recombinant human interleukin 1 receptor antagonist in the treatment of patients with sepsis syndrome. Results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Phase III rhIL-1ra Sepsis Syndrome Study Group. JAMA. 1994;271(23):1836-1843 [PubMed]

- 16937360 Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Imashuku S, Ladisch S, McClain K, Webb D, Winiarski J, Janka G. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007 Feb;48(2):124-31. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21039 [PubMed]

- 17106167 Ando M, Miyazaki E, Hiroshige S, Ashihara Y, Okubo T, Ueo M, Fukami T, Sugisaki K, Tsuda T, Ohishi K, Yoshitake S, Noguchi T, Kumamoto T. Virus associated hemophagocytic syndrome accompanied by acute respiratory failure caused by influenza A (H3N2). Intern Med. 2006;45(20):1183-6. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.45.1736 [PubMed]

- 20348529 Zheng Y, Yang Y, Zhao W, Wang H. Novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome–a first case report. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010 Apr;82(4):743-5. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0666 [PubMed]

- 21366922 Beutel G, Wiesner O, Eder M, Hafer C, Schneider AS, Kielstein JT, Kühn C, Heim A, Ganzenmüller T, Kreipe HH, Haverich A, Tecklenburg A, Ganser A, Welte T, Hoeper MM. Virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome as a major contributor to death in patients with 2009 influenza A (H1N1) infection. Crit Care. 2011;15(2):R80. doi: 10.1186/cc10073 [PubMed]

- 22286408 Asai N, Ohkuni Y, Matsunuma R, Iwama K, Otsuka Y, Kawamura Y, Motojima S, Kaneko N. A case of novel swine influenza A (H1N1) pneumonia complicated with virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome. J Infect Chemother. 2012 Oct;18(5):771-4. doi: 10.1007/s10156-011-0366-3 [PubMed]

- 23965472 Moore C Jr, Ormseth M, Fuchs H. Causes and significance of markedly elevated serum ferritin levels in an academic medical center. J Clin Rheumatol. 2013;19(6):324-328. doi:10.1097/RHU.0b013e31829ce01f [PubMed]

- 24583503 Rajasekaran S, Kruse K, Kovey K, Davis AT, Hassan NE, Ndika AN, Zuiderveen S, Birmingham J. Therapeutic role of anakinra, an interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, in the management of secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis/sepsis/multiple organ dysfunction/macrophage activating syndrome in critically ill children*. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014 Jun;15(5):401-8. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000078. PMID: 24583503 [PubMed]

- 25851400 Wormsbecker AJ, Sweet DD, Mann SL, Wang SY, Pudek MR, Chen LY. Conditions associated with extreme hyperferritinaemia (>3000 μg/L) in adults. Intern Med J. 2015;45(8):828-833. doi:10.1111/imj.12768 [PubMed]

- 26154908 Carcillo JA, Simon DW, Podd BS. How We Manage Hyperferritinemic Sepsis-Related Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome/Macrophage Activation Syndrome/Secondary Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis Histiocytosis. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015 Jul;16(6):598-600. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000460. PMID: 26154908; PMCID: PMC5091295. [PubMed]

- 26584195 Shakoory B, Carcillo JA, Chatham WW, et al. Interleukin-1 Receptor Blockade Is Associated With Reduced Mortality in Sepsis Patients With Features of Macrophage Activation Syndrome: Reanalysis of a Prior Phase III Trial. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(2):275-281. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000001402 [PubMed]

- 28631531 Wohlfarth P, Agis H, Gualdoni GA, Weber J, Staudinger T, Schellongowski P, Robak O. Interleukin 1 Receptor Antagonist Anakinra, Intravenous Immunoglobulin, and Corticosteroids in the Management of Critically Ill Adult Patients With Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. J Intensive Care Med. 2019 Sep;34(9):723-731. doi: 10.1177/0885066617711386 [PubMed]

- 27247369 Sackett K, Cunderlik M, Sahni N, Killeen AA, Olson AP. Extreme Hyperferritinemia: Causes and Impact on Diagnostic Reasoning. Am J Clin Pathol. 2016;145(5):646-650. doi:10.1093/ajcp/aqw053 [PubMed]

- 27292929 Brisse E, Matthys P, Wouters CH. Understanding the spectrum of haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: update on diagnostic challenges and therapeutic options. Br J Haematol. 2016;174(2):175-187. doi:10.1111/bjh.14144 [PubMed]

- 27298397 Debaugnies F, Mahadeb B, Ferster A, Meuleman N, Rozen L, Demulder A, Corazza F. Performances of the H-Score for Diagnosis of Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis in Adult and Pediatric Patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 2016 Jun;145(6):862-70. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqw076 [PubMed]

- 27697804 Thomas W, Veer MV, Besser M. Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: an elusive syndrome. Clin Med (Lond). 2016;16(5):432-436. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.16-5-432 [PubMed]

- 28052298 Hanoun M, Dührsen U. The Maze of Diagnosing Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis: Single-Center Experience of a Series of 6 Clinical Cases. Oncology. 2017;92(3):173-178. doi:10.1159/000454733 [PubMed]

- 28120605 Akenroye AT, Madan N, Mohammadi F, Leider J. Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis mimics many common conditions: case series and review of literature. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;49(1):31-41 [PubMed]

- 28477737 Machowicz R, Janka G, Wiktor-Jedrzejczak W. Similar but not the same: Differential diagnosis of HLH and sepsis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2017;114:1-12. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2017.03.023 [PubMed]

- 28631531 Wohlfarth P, Agis H, Gualdoni GA, et al. Interleukin 1 Receptor Antagonist Anakinra, Intravenous Immunoglobulin, and Corticosteroids in the Management of Critically Ill Adult Patients With Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. J Intensive Care Med. 2019;34(9):723-731. doi:10.1177/0885066617711386 [PubMed]

- 28762079 Otrock ZK, Hock KG, Riley SB, de Witte T, Eby CS, Scott MG. Elevated serum ferritin is not specific for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Ann Hematol. 2017;96(10):1667-1672. doi:10.1007/s00277-017-3072-0 [PubMed]

- 28871523 Kumar B, Aleem S, Saleh H, Petts J, Ballas ZK. A Personalized Diagnostic and Treatment Approach for Macrophage Activation Syndrome and Secondary Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis in Adults. J Clin Immunol. 2017 Oct;37(7):638-643. doi: 10.1007/s10875-017-0439-x [PubMed]

- 29417621 Zandvakili I, Conboy CB, Ayed AO, Cathcart-Rake EJ, Tefferi A. Ruxolitinib as first-line treatment in secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: A second experience. Am J Hematol. 2018;93(5):E123-E125. doi:10.1002/ajh.25063 [PubMed]

- 30075527 Merrill SA, Naik R, Streiff MB, Shanbhag S, Lanzkron S, Braunstein EM, Moliterno AM, Brodsky RA. A prospective quality improvement initiative in adult hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis to improve testing and a framework to facilitate trigger identification and mitigate hemorrhage from retrospective analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 Aug;97(31):e11579. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011579 [PubMed]

- 30384814 Lemiale V, Valade S, Calvet L, Mariotte E. Management of Hemophagocytic Lympho-Histiocytosis in Critically Ill Patients. J Intensive Care Med. 2020;35(2):118-127. doi:10.1177/0885066618810403 [PubMed]

- 30766533 Karakike E, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ. Macrophage Activation-Like Syndrome: A Distinct Entity Leading to Early Death in Sepsis. Front Immunol. 2019;10:55. Published 2019 Jan 31. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00055 [PubMed]

- 30992265 La Rosée P, Horne A, Hines M, et al. Recommendations for the management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Blood. 2019;133(23):2465-2477. doi:10.1182/blood.2018894618 [PubMed]

- 31339233 Jordan MB, Allen CE, Greenberg J, et al. Challenges in the diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: Recommendations from the North American Consortium for Histiocytosis (NACHO). Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66(11):e27929. doi:10.1002/pbc.27929 [PubMed]

- 31515353 Wang J, Wang Y, Wu L, et al. Ruxolitinib for refractory/relapsed hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Haematologica. 2020;105(5):e210-e212. doi:10.3324/haematol.2019.222471 [PubMed]

- 31537486 Ahmed A, Merrill SA, Alsawah F, et al. Ruxolitinib in adult patients with secondary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: an open-label, single-centre, pilot trial. Lancet Haematol. 2019;6(12):e630-e637. doi:10.1016/S2352-3026(19)30156-5 [PubMed]

- 31991015 Naymagon L, Tremblay D, Mascarenhas J. Reevaluating the role of ferritin in the diagnosis of adult secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Eur J Haematol. 2020;104(4):344-351. doi:10.1111/ejh.13391 [PubMed]

- 31995958 Belfeki N, Strazzulla A, Picque M, Diamantis S. Extreme hyperferritinemia: etiological spectrum and impact on prognosis. Reumatismo. 2020;71(4):199-202. Published 2020 Jan 28. doi:10.4081/reumatismo.2019.1221 [PubMed]

- 32285358 Gálvez Acosta S, Javalera Rincón M. Ruxolitinib as first-line therapy in secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and HIV infection. Int J Hematol. 2020;112(3):418-421. doi:10.1007/s12185-020-02882-1 [PubMed]

- 32387063 Griffin G, Shenoi S, Hughes GC. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: An update on pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 7]. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2020;101515. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2020.101515 [PubMed]

- 32470486 Cao Y, Wei J, Zou L, et al. Ruxolitinib in treatment of severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A multicenter, single-blind, randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(1):137-146.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2020.05.019 [PubMed]

- 34950412 Han HJ, Parks AL, Shah MP, Hsu G, Santhosh L. An Elusive Seizure. Neurohospitalist. 2022 Jan;12(1):188-194. doi: 10.1177/19418744211018096 [PubMed]