CONTENTS

- Rapid Reference 🚀

- Definition of severe CAP

- Diagnosis:

- Post-diagnosis evaluation:

- Triage: who needs ICU?

- Treatment

- Treatment failure

- Duration of treatment ➡️

- Podcast

- Questions & discussion

- Pitfalls

#1/2: investigations ✅

history

- Travel?

- Animal exposure in last 1-2 months?

- Residence in TB-endemic country?

- Recent healthcare contact? (admission, IV antibiotics?)

- Review prior culture results (drug-resistant organisms?)

- Upper respiratory tract symptoms (e.g. pharyngitis, rhinitis, hoarseness)? (May suggest Mycoplasma, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Chlamydia psittaci, tularemia, influenza, RSV, metapneumovirus, adenovirus, EBV, HSV, group A streptococcus). (23594007)

labs

- Blood cultures x2.

- Sputum:

- Sputum gram stain & culture if feasible (especially if intubated).

- (May also consider sputum for fungus smear & culture.)

- Nares:

- Nares PCR for MRSA.

- Nasopharyngeal PCR: COVID, relevant viruses (e.g., influenza).

- Procalcitonin and C-reactive protein (CRP).

- Urine legionella & pneumococcal antigens.

- Consider HIV serology.

imaging

- Review chest radiograph.

- If imaging suggests effusion: POCUS.

- Consider CT scan if:

- Pneumonia diagnosis is uncertain (e.g., vs PE).

- Substantial immunocompromise.

- Unusual radiograph (e.g., cavities/nodules).

#2/2: management ✅

supportive care

- High-flow nasal cannula if significant dyspnea. 📖

- Consider steroid if no contraindication (e.g., 50 mg/day prednisone, or 40 mg/day methylprednisolone). 📖

- Avoid large-volume fluid resuscitation. 📖

atypical coverage

- Usually azithromycin 💉 500 mg IV daily x3 days. (Azithromycin is safe regardless of QTc and can be used in nearly all patients.)

- Alternative: Doxycycline 💉 100 PO/IV BID instead of azithromycin. Consider this in three situations:

- (1) Animal exposure (covers zoonotic pneumonias).

- (2) High risk for C. difficile infection (doxy reduces risk).

- (3) Patients are at some risk for community-acquired MRSA pneumonia, but not enough risk to justify linezolid/vancomycin (doxycycline has fair activity against MRSA in vitro, but lacks evidence for efficacy in MRSA pneumonia).

beta-lactam backbone

- Usually ceftriaxone 💉, 1-2 grams daily.

- Consider cefepime 💉 or piperacillin-tazobactam 💉 if risk for pseudomonas:

- Structural lung disease (e.g. bronchiectasis, tracheostomy, or very severe COPD with frequent exacerbations).

- Broad-spectrum antibiotics for >7 days within past month.

- Hospitalization with IV antibiotics for >1 day within past three months.

- Immunocompromise (e.g. chemotherapy, chronic use of >10 mg prednisone daily).

- Nursing home resident with poor functional status.

- History of pseudomonas infection or colonization.(34481570)

consider MRSA coverage

- Figure below indicates if MRSA coverage is required. If so:

definition of community acquired pneumonia (CAP)

- Community-acquired pneumonia refers to a pneumonia which begins when the patient is outside the hospital, or within the first <48 hours of hospital admission.

- “Healthcare-associated pneumonia” is no longer considered a valid diagnostic entity (based on evidence that this categorization fails to accurately identify patients harboring drug-resistant organisms). Such patients are now considered to have community-acquired pneumonia.

definition of severe community acquired pneumonia

- Severe community-acquired pneumonia is generally defined as patients admitted to the ICU.(35190510)

diagnosis is generally based on three lines of evidence:

- (1) Imaging evidence of a chest infiltrate (e.g., CXR, CT, ultrasound).

- (2) Systemic inflammation:

- Symptoms: Night sweats, rigors, fevers.

- Signs: Fever or hypothermia.

- Labs: Leukocytosis, left-shift, elevated C-reactive protein, elevated procalcitonin.

- (3) Localizing signs and symptoms:

- Symptoms: Dyspnea, cough, sputum production, pleuritic chest pain.

- Signs: Hypoxemia, tachypnea, abnormal lung auscultation.

atypical presentations

- Elderly patients may present with non-pulmonary complaints:

- Falls.

- Delirium.

- Sepsis.

- When in doubt, it is reasonable to get cultures and start antibiotics for pneumonia. Within the next 24-48 hours, the diagnosis may be re-considered and antibiotics discontinued as appropriate.

CT scan to assist the diagnosis of pneumonia

- Some patients with pneumonia will have a negative radiograph with a positive CT scan. Causes of reduced sensitivity of radiograph include:(Murray 2022)

- Underlying structural lung disease (e.g., emphysema, bullae).

- Severe obesity.

- Neutropenia.

- Very early in the disease course.

- CT scan can be especially helpful to detect pneumonia in patients with chronic lung disease and chronically abnormal radiograph (especially if a prior CT scan is available for comparison).

- Evidence supports the use of CT scan for pneumonia diagnosis:

- One series found that a third of patients with suspected pneumonia and a negative radiograph had infiltrates detected by CT scan. These radiograph-negative, CT-positive patients had outcomes similar to patients with infiltrates on radiography, substantiating that these are “real” pneumonias detected on CT scan.(26168322)

- Among 188 patients with infiltrates detected on radiograph, pneumonia was excluded by chest CT scan in nearly a third of patients. Prompt exclusion of pneumonia facilitates antibiotic stewardship and (more importantly) redirection of attention to the actual cause of the patient's illness.(26168322)

- 💡 Among patients who are older and unlikely to harmed by radiation, there should probably be a reduced threshold to obtain CT scan to facilitate prompt diagnosis and accurate therapy.

bronchoscopy – discussed further below 📖

Below are some common considerations:

pulmonary embolism

- Clues:

- Wedge-shaped pulmonary infarcts may masquerade as PNA.

- Pulmonary infiltrates may be unimpressive, compared to symptoms.

- Right ventricular strain pattern on EKG/Echo.

- Signs/symptoms of DVT (leg swelling, pain).

- Diagnostic tests: CT angiography.

septic pulmonary emboli

- Clues:

- Diffuse infiltrates which tend to cavitate.

- Often bacteremic with staph aureus.

- Often seen in patients with intravenous drug use.

- Diagnostic tests:

- CT scan shows characteristic pattern with multi-focal cavitation.

- Echocardiogram shows tricuspid vegetation.

PJP (Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia)

- Clues:

- HIV (if the diagnosis is known).

- Non-HIV: Chronic steroid use (>15 mg prednisone for >3 weeks), chemotherapy/immunosuppressive drugs.

- Diffuse interstitial infiltrates.

- Diagnostic tests:

- HIV serology is crucial to diagnosis of HIV-PJP.

- Bronchoscopy with BAL sent for fungal stain & PCR.

endemic fungal pneumonia or cryptococcus

- Clues:

- Often more indolent than bacterial pneumonia.

- Radiologic pattern often nodular.

- Can affect normal hosts (blastomycosis), but often affects immunocompromised patients (esp: TNF-inhibitors & steroid).

- Exposure to endemic locations, bird/bat droppings (histoplasmosis), soil exposure (blastomycosis, coccidiomycosis).

- Diagnostic tests:

- Urine antigens (e.g., blastomycosis, histoplasmosis).

- Serum antigen for cryptococcus (CrAg).

- CT scan can be suggestive.

- Bronchoscopy.

invasive aspergillosis

- Clues:

- Neutropenia (especially >10 days)

- High-dose steroid (e.g., pulse therapy for vasculitis)

- Diagnostic tests:

- CT scan may help risk stratify.

- Beta-D-Glucan, galactomannan.

- Bronchoscopy.

tuberculosis

- Clues:

- Longer duration of symptoms.

- History of night sweats, weight loss, or hemoptysis.

- Epidemiologic risk factors for tuberculosis.

- Radiology showing cavitation, upper lobe involvement, or absence of air bronchograms.(30838060)

- Diagnostic tests:

- CT scan may help risk stratify.

- Sputum for AFB smear/culture and TB PCR.

DAH (diffuse alveolar hemorrhage)

- Clues:

- Hemoptysis (only 50% of patients however).

- Diffuse infiltrates.

- Renal failure or active urinary sediment (hematuria).

- Falling hemoglobin.

- May have previously diagnosed rheumatologic disease.

- Diagnostic tests:

- Urinalysis: hematuria.

- Markedly elevated ESR & CRP.

- Bronchoscopy shows alveolar hemorrhage.

- Serologies can be helpful (e.g. ANCA).

AEP (acute eosinophilic pneumonia)

- Clues:

- Blood eosinophils over ~300/uL (unusual for severe pneumonia).

- Younger adults with severe PNA, often requiring intubation.

- Sometimes inhalational exposure (esp. recent-onset smoking).

- Diagnostic tests:

- Bronchoscopy shows alveolar eosinophilia.

OP (organizing pneumonia)

- Clues:

- Often more gradual onset than usual PNA.

- Refractory to antibiotics.

- Radiographic features may be suggestive (e.g., perilobular opacities, migratory opacities).

- Diagnostic tests:

- Hard to diagnose (tissue biopsy needed).

drug- or radiation-induced pneumonitis

- Clues:

- Exposure to drug implicated in causing pneumonitis.

- Most often: amiodarone, chemotherapeutics.

- Diagnostic tests:

- Hard to diagnose.

- Often diagnosis of exclusion, treated empirically.

- Radiation pneumonitis may have a focal, non-anatomic distribution corresponding to the radiation field.

flare of ILD (interstitial lung disease)

- Clues:

- History of chronic pulmonary limitation.

- Prior diagnosis of interstitial lung disease (often idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis).

- Diagnostic tests:

- CT scan may be suggestive (e.g., honeycomb scarring).

- ILD exacerbation is a diagnosis of exclusion.

exacerbation of COPD

- Clues:

- COPD exacerbation may clinically mimic pneumonia including hypoxemia, fever, and sputum production. This can be nearly impossible to sort out based on history and physical examination.

- Diagnostic tests:

- Isolated COPD exacerbation should lack infiltrates on chest imaging and have a relatively low procalcitonin level.

- Note that COPD exacerbation can coexist with bacterial pneumonia (“pneumonic COPD exacerbation”) – in which case both processes should be treated simultaneously.

atelectasis (+/- non-pulmonary infection)

- Clues:

- Clinical illness severity is disproportionate to the radiograph (which often isn't impressive).

- Lack of prominent pulmonary symptoms.

- Diagnostic tests:

- CT chest may be helpful to exclude severe pneumonia.

- Best diagnostic strategy is to find an alternative diagnosis.

- 💡 A common error is to assume that the septic shock must be due to pneumonia, when in fact the chest opacities are a red herring. When in doubt, err on the side of investigating further to exclude an alternative source of sepsis.

aspiration pneumonitis

- Clues:

- History of aspiration or swallowing problems.

- Repeated episodes of pneumonia with rapid recovery.

- Infiltrates located in dependent lung segments.

- Diagnostic tests:

- May be impossible to diagnose up-front.

- CXR clears very rapidly (over 24-48 hours).

- Procalcitonin is often negative.

blood cultures

- Recommended for severe pneumonia, although yield is low (~10%).(29968985)

- ⚠️ If patient already had blood cultures at another hospital, don't repeat them (follow up on results from the outside hospital lab).

sputum for gram stain & culture for bacteria

- Overall utility:

- Intubated patient: tracheal aspirate is very useful.

- Non-intubated patient: expectorated sputum is only occasionally useful, yet still recommended.(29968985) Many patients are incapable of producing sputum.

- Quality:

- A high-quality sputum sample should have >25 leukocytes and <10 squamous cells per low-power field.(Murray 2022) >10 squamous epithelial cells per low-power field indicates excessive oropharyngeal contamination, so the specimen should be discarded.

- If a good-quality sputum culture reveals a single dominant morphology of bacteria on gram stain, that is strong evidence regarding the etiology of pneumonia.

- If numerous different morphologies of bacteria are seen in similar amounts, then the sputum gram stain is often meaningless (reflective of normal flora).

- Sensitivity of sputum culture for different organisms:

- Streptococcus pneumoniae or Haemophilus influenzae are fastidious organisms that are difficult to grow. Consequently, sputum culture is often negative.

- Staphylococcus aureus and gram-negatives tend to grow exuberantly, even if they merely represent colonization. If sputum culture is positive for Staphylococcus aureus or a gram-negative organism but this isn't seen in a high-quality sputum sample, it's dubious whether the sputum culture truly reflects pneumonia.(Murray 2022)

sputum for fungus culture & smear

- Fungal smear typically involves a combination of potassium hydroxide and Calcofluor white. Potassium hydroxide dissolves human tissue (but not fungi), removing debris from the slide.

- Fungal culture and smear should be ordered if imaging or epidemiological data suggests the possibility of a fungal pneumonia (e.g., blastomycosis, histoplasmosis, cryptococcus neoformans, coccidiomycosis).

urine legionella antigen

- Sensitivity ~75% and specificity of ~95%.(29968985)

- A negative result doesn't exclude legionella.

- A positive result is important, since patients with legionella may benefit from extended courses of antibiotic (e.g., azithromycin 500 mg IV daily for 7-10 days, instead of three days).

urine pneumococcal antigen

- Sensitivity ~75% and specificity 95%.

- False-positive may occur due to pneumonia within the past several weeks, or recent pneumococcal vaccination.(29968985, 29119848)

nares PCR for MRSA

- MRSA nares PCR can be reliably used to guide empiric and targeted antibiotic therapy, with a negative predictive value of 96-99%.(32127438, 32101906)

nasopharyngeal PCR for COVID and viruses (e.g. influenza).

- If nasopharyngeal influenza PCR is negative and high suspicion remains, a lower respiratory tract PCR may be positive.(21048054)

- Be careful: patients may be co-infected with viral and bacterial pathogens. Just because the viral PCR is positive doesn't mean that you should stop antibacterial therapy.(29968985)

inflammatory markers

HIV screening test

- Consider for any patient who is at potential risk.

- Yield is low, but when positive this has enormous implications for patient management.

imaging modality

- Radiograph:

- Useful for all patients.

- Global study may be useful to track progress over time.

- CT scan may be indicated for more advanced evaluation, for example in patients with:

- Immunocompromise.

- Unusual chest imaging (e.g. radiograph suggests nodular/cavitating pneumonia).

- Ultrasonography:

- (1) Effusion:

- Bedside ultrasonography is mandatory if there is any doubt regarding possible effusion (e.g. basilar opacities).

- Among patients with large radiographic opacities that could hide an effusion, ultrasonography should be repeated every 1-2 days to surveil for the development of effusion/empyema.

- (2) Detection of a dense consolidation with dynamic air bronchograms supports the possibility of lobar pneumonia.

- (1) Effusion:

radiologic patterns of pneumonia

- Radiologic patterns of pneumonia cannot entirely be relied upon. However, they can provide useful diagnostic clues, so they shouldn't be ignored either.

- Specific radiographic patterns are discussed below:

lobar consolidation (lobar pneumonia)

clinical features

- Pleural extension often causes pleuritic chest pain.

- Sputum production may be minimal or unimpressive.

radiographic features

- Key features:

- Single or multiple large areas of dense consolidation (not necessarily involving an entire lobe, despite the name “lobar pneumonia”). Areas outside of consolidated regions are spared. Consolidation may extend to the lobar fissures, creating sharp borders.

- Air bronchograms may be seen. When present, these argue against a central bronchial obstruction as causing the pneumonia.(Shepard 2019)

- Pleural effusion is often associated.

- Other findings that may occur:

- Bulging fissure sign may result from expansion of the affected lobe. This is classically associated with Klebsiella, but can occur with any lobar pneumonia.(Shepard 2019) In practice, it is most often associated with Streptococcus pneumoniae.(Walker 2019)

- Round pneumonia is a term referring to a single focus of consolidative pneumonia with a round contour. This is a subset of lobar pneumonia, with similar treatment implications. However, additional diagnostic considerations might include Coxiella burnetii, fungi, or early septic emboli.(Shepard 2019)

common causes of lobar pneumonia

- Streptococcus pneumoniae.

- Haemophilus influenzae.

- Klebsiella pneumoniae.

- Legionella pneumophila.

- (M. tuberculosis may rarely cause this, as a component of primary tuberculosis.)

bronchopneumonia (aka lobular pneumonia)

clinical features

- Productive cough is often seen.

radiographic features

- Radiograph:

- Patchy, multifocal opacities.

- Air bronchograms are typically absent.

- CT scan:

- Centrilobular nodular opacities:

- Ill-defined, ~5-10 mm.

- May form a tree-in-bud pattern.

- Reflects endobronchial spread of the infection.

- Bronchial wall thickening.

- Mosaic attenuation due to hyperinflation may result from widespread inflammation of the bronchial walls with luminal obstruction.(Walker 2019)

- Lobular ground-glass opacities and consolidation:

- Opacities are patchy and often surrounded by ground glass opacification.

- In severe cases, consolidated lobules may progress to the point of confluence (which may become indistinguishable from a lobar pneumonia).(Shepard 2019)

- A peribronchovascular distribution may be discernible.(31200868)

- Centrilobular nodular opacities:

- Radiological differential diagnosis includes:

- Acute bronchiolitis may blend into bronchopneumonia.

commonly implicated organisms

- Typical bacterial infections:

- Staphylococcus aureus.

- Pseudomonas and other gram negative organisms.

- Nonencapsulated Haemophilus influenzae.

- Atypical bacteria: Mycoplasma, chlamydiae.

- Viral pneumonia:

- Especially: influenza, parainfluenza, RSV, metapneumovirus.

- Also: HSV, CMV, adenovirus.

interstitial pneumonia

radiologic features

- Diffuse ground glass opacities.

- Septal thickening.

causes

- Mycoplasma, chlamydia.

- Viral pneumonia (e.g., influenza).

- Pneumocystis jiroveci (PJP).

- Noninfectious mimics: heart failure, lymphangitic carcinomatosis, drug-induced pneumonitis.

necrotizing pneumonia (causing lung abscess and cavitation)

clinical presentation

- Patients are usually acutely, severely ill:(30844921)

- Illness develops over a few days.

- Patients often present with sepsis.

- (This helps distinguish necrotizing pneumonia from more indolent infections, such as tuberculosis or nocardia.)

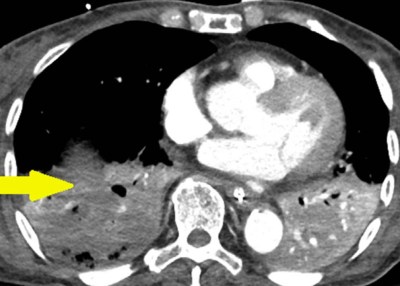

radiological findings

- Cavitation is the hallmark finding, but it is not invariably present. Cavitation generally occurs within areas of consolidation.

- Fluid-filled cavities may likewise be seen, with either thin or thick wall (if these are surrounded by a thick wall, then they would be classified as abscesses).(30844921)

- Contrast non-enhancement identifies areas of necrotic lung (figure below).

related differential diagnoses to consider

- If multiple, prominent bilateral cavities are seen:

- Septic pulmonary emboli.

- Nocardia.

- Actinomyces.

- Fungal pneumonia.

- Tuberculosis.

- If unilateral, with cavity larger than infiltrate: consider anaerobic lung abscess.

common causes of necrotizing bacterial pneumonia

- Gram positives:

- Staphylococci (especially community-acquired toxigenic MRSA).

- Pyogenic streptococci (groups A-D).

- Streptococcus pneumoniae.

- Gram negative bacteria (e.g., Pseudomonas, Klebsiella, Proteus, Serratia).

- Less common pathogens may include:

- Haemophilus influenzae type b.

- Legionella.

- Anaerobes may cause abscess formation, but this is usually within the context of a primary lung abscess (rather than a primary pneumonia with secondary necrosis). However, it is conceivable that in some cases a pneumonia due to aerobic bacteria may become superinfected with oral anaerobes, leading to abscess formation. (30844921)

management

- Necrotizing pneumonia is fundamentally a severe form of CAP, which should be treated based on the same general principles. However, the presence of tissue necrosis indicates increased risk of permanent organ damage, so more aggressive therapy may be reasonable.

- Considerations for initial empiric antibiotic therapy:

- (1) MRSA coverage is generally indicated. For necrotizing pneumonia due to toxigenic strains of Staphylococcus aureus, a toxin-suppressive antibiotic might be especially beneficial (e.g., linezolid).

- (2) Pseudomonas coverage is reasonable, given that Pseudomonas can present with a cavitary pneumonia. Pseudomonal coverage will also provide strong coverage of other gram-negative organisms that frequently cause cavitary pneumonia (e.g., Klebsiella spp.).

- (3) Anaerobic coverage is reasonable, until a pathogen has been identified. Piperacillin-tazobactam or meropenem are reasonable choices here, to cover both Pseudomonas and anaerobes.

- (4) Legionella coverage may be considered initially.

- For example, a combination of linezolid, doxycycline, and piperacillin-tazobactam would be reasonable initially. As always, antibiotics should be rapidly de-escalated as culture data becomes available.

- Interventional therapies:

- If present, empyema should be managed in the usual fashion (e.g., with chest tube drainage).

- Surgery may be needed for treatment-refractory necrotizing infection that leads to extensive tissue necrosis (lung gangrene). (29518379)

nodular pneumonia pattern

- Fungal pneumonia, nocardia, mycobacterial (all of these usually indolent).

- Septic pulmonary emboli (prior to cavitation).

- Non-infectious (e.g. malignancy, granulomatosis with polyangiitis).

pleural effusion associated with pneumonia

- Not very specific.

- Effusion may be most commonly associated with: pneumococcus, haemophilus influenzae, group A streptococcus, legionella.

pneumothorax associated with pneumonia

- Septic pulmonary emboli may cause cavitation and then pneumothorax.

- Pneumocystis jiroveci.

invasion beyond the pleura, for example destruction of the ribs/sternum, or fistulization to the skin (empyema necessitans)

causes of chest wall invasion

- (#1) Tuberculosis.

- (#2) Actinomycosis.

- Nocardia.

- Fungal infections:

- Blastomycosis.

- Coccidiomycosis.

- Sporotrichosis.

- Aspergillus, mucormycosis.

- Rarely, empyema necessitans may be due to other bacterial infections (e.g., fusobacterium, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus milleri, Bacteroides, Citrobacter freundii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa).(36759118) This may also result from an empyema occuring after thoracic surgery or trauma (which allows the infection to track into surrounding tissues).(36088098)

investigations to consider

- Ultrasonography may define whether there is a fluid collection within the chest wall.

- CT scan with IV contrast is the study of choice:

- If there is a drainable collection within the chest wall, this may be diagnostically aspirated using ultrasonographic guidance.(24798841)

management may involve a combination of

- Appropriate antimicrobial therapy.

- Chest tube drainage for management of an underlying empyema.

- Surgical consultation to manage the chest wall collection.

Bronchoscopy is only rarely useful in the management of community-acquired pneumonia.

bronchoscopy for the diagnosis of bacterial community-acquired pneumonia

- Bronchoscopy is occasionally useful to exclude a non-infectious pneumonia mimic (e.g. diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, eosinophilic pneumonia).

- Bronchoscopy may be useful to exclude an unusual infection, primarily:

- Fungal pneumonia.

- PJP (pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia).

- The indications for bronchoscopy are predominantly indicators that patients may have a non-bacterial process, for example:

- CT scan shows cavitation, nodules, and/or diffuse ground glass opacification.

- The patient is profoundly immunocompromised, increasing the risk of unusual organisms.

performance of bronchoscopy for bacterial pathogens

- Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) is subject to contamination with oropharyngeal flora, so culturing an organism doesn't necessarily indicate that it represents an invasive pneumonia. (This may be reduced by the use of protected brush cultures.)

- When bronchoscopy is used to obtain different specimens, there is a 20-40% rate of disagreement between the different specimens!

- Overall, the sensitivity and specificity of bronchoscopy for bacterial culture is unimpressive.

No criteria apply perfectly for every patient. However, the IDSA/ATS criteria may provide a useful conceptual framework for borderline situations.

classic errors in pneumonia triage

- (1) Triage solely based on the amount of oxygen the patient requires:

- A common myth is that if the patient can saturate adequately on nasal cannula then it's OK for them to go to the ward. This is completely and utterly wrong.

- (2) Triage based on CURB65 and PORT scores:

- These are validated as mortality prediction tools, they aren't designed to determine disposition.

- These scores are not great at sorting out who needs the ward vs. ICU.

IDSA/ATS criteria for severe pneumonia (i.e., ICU admission)

- These criteria have been validated for use in triage to the ICU versus ward. Severe pneumonia is defined by either having at least one major criteria, or at least three minor criteria.(29609223, 21865188, 19789456)

- Major criteria (only 1 required):

- Respiratory distress requiring mechanical ventilation. These criteria were created prior to the common use of high-flow nasal cannula. A patient with substantial work of breathing or tachypnea (e.g., respiratory rate >30) who requires high-flow nasal cannula should be considered for ICU admission.(29119848, 18513176)

- Septic shock.

- Minor criteria (at least 3 required):

- Respiratory rate >29 breaths/min.

- Hypotension requiring volume resuscitation.

- PaO2/FiO2 <250 (very roughly may correspond to requiring >3 liters oxygen).(17573487)

- Temperature <36C.

- Confusion.

- Multi-lobar infiltrates.

- BUN >20 mg/dL (>7 mM).

- WBC <4,000/mm3.

- Platelets <100,000/mm3.

don't forget atypical coverage!

don't forget atypical coverage!

- Atypical coverage should always be included in the empiric antibiotic regimen for severe pneumonia.

- Legionella causes ~10-15% of severe pneumonia. This won't be covered by the broadest beta-lactams in the world (e.g. cefepime, piperacillin-tazobactam, meropenem).

- Azithromycin 💉 is an excellent choice here:

- Solid track record in pneumonia.

- Retrospective studies suggest mortality benefit, even in pneumococcal pneumonia sensitive to beta-lactams (possibly due to anti-inflammatory activity, or coinfection with atypical pathogens).

- If the patient is diagnosed with pneumococcus, azithromycin should still be continued for 3-5 days.(17452932, 30118377)

- Azithromycin is well-tolerated and very safe. Don't worry about the QT interval, the concept that azithromycin causes torsade de pointes is mythological.(24893087)

- Doxycycline 💉 is also an excellent choice for atypical coverage, with the following advantages:

- Doxycycline covers most organisms acquired from animal contact:

- Coxiella burnetii (Q-fever) – usually seen in farmers or veterinarians due to contact with cattle, sheep, goats, cats, dogs, or rabbits.

- Tularemia – acquired from rabbits

- Leptospirosis – acquired from animal urine.

- Psittacosis – acquired from birds.

- Doxycycline is generally active against MRSA in vitro, but it's unclear whether this is effective for clinical MRSA pneumonia.

- Doxycycline appears to reduce the risk of C. difficile infection. (37921728, 22563022)

- Doxycycline covers most organisms acquired from animal contact:

- Fluoroquinolones are a poor choice for atypical coverage in the ICU for several reasons. 🌊

beta-lactam backbone

- The beta-lactam backbone will cover gram-positives (especially pneumococcus) and gram negatives.

- Ceftriaxone 💉 is an excellent choice for most patients.

- It's controversial whether to use 1 or 2 grams IV daily. Increasing drug resistance over time may be an argument to use 2 grams. This should also be considered in obese patients.

- Ceftriaxone is safe to use in most patients with penicillin allergy. 📖

- Antipseudomonal beta-lactam (piperacillin-tazobactam 💉 or cefepime 💉) may be considered in patients with risk factors for pseudomonas, for example:

- Structural lung disease (e.g. bronchiectasis, tracheostomy, or very severe COPD with frequent exacerbations).

- Broad-spectrum antibiotics for >7 days within past month.

- Hospitalization with IV antibiotics for >1 day within past three months.

- Immunocompromise (e.g. chemotherapy, chronic use of >10 mg prednisone daily).

- Nursing home resident with poor functional status.

- History of pseudomonas infection or colonization.(34481570)

- Patients with penicillin allergy can generally receive these antibiotics without an issue (discussed further here: 📖).

MRSA coverage is occasionally needed as 3rd drug

- MRSA is an uncommon cause of community-acquired pneumonia, with rates of ~1-3%.(32101906, 32805298) This varies depending on geography and patient population, but overall most patients with community acquired pneumonia do not need MRSA coverage.

- Risk factors for MRSA are different from risk factors for drug-resistant gram negative organisms. Thus, a one-size-fits-all approach towards all drug-resistant organisms is suboptimal. A tailored strategy to guide the use of MRSA coverage is shown above.(more detail here)

- Regardless of the exact approach used, the key is ongoing and thoughtful evaluation of data.

- Staph generates lots of purulent sputum and is generally not difficult to isolate.

- MRSA PCR has an excellent negative predictive value, so a negative PCR can often allow for discontinuation of MRSA coverage.(32127438, 32101906)

- MRSA coverage should be stopped within <48-72 hours unless there is some objective data that the patient has MRSA.

- Cavitary pneumonia raises the possibility of Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) toxin-producing strains of MRSA. These strains are often community-acquired and extremely aggressive, causing necrotizing pneumonia among otherwise healthy individuals. Optimal therapy might include toxin-suppressive antibiotics (e.g., linezolid +/- rifampicin).(35190510)

- Choice of agent:

- Linezolid 💉 is arguably first-line therapy for MRSA pneumonia (compared to vancomycin, linezolid has superior lung penetration, causes no nephrotoxicity, and suppresses bacterial toxin synthesis).(26859379, 22247123)

- Vancomycin 💉 is the traditional option if linezolid is contraindicated. Unfortunately, resistance to vancomycin is increasing over time. If susceptibility testing shows borderline sensitivity to vancomycin (MIC 1.5-2 mcg/mL) this may increase the risk of treatment failure and an alternative agent might be better. If the MIC is >2 mcg/mL then a different antibiotic should definitely be used.

- Ceftaroline 💉 is a fifth-generation cephalosporin active against MRSA. It might be superior to vancomycin (particularly for strains with MIC>1 mcg/mL), but there is no high-quality evidence available.(28702467, 29147471)

- (Daptomycin isn't an option here because it is degraded by surfactant and thus cannot treat pneumonia.)

double-coverage for pseudomonas is not needed

- Unless you're living in a post-apocalyptic hellscape where pseudomonas are insanely resistant to beta-lactams, this shouldn't be necessary. Double-coverage doesn't even appear to benefit patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia (which involves a much greater risk of resistant pseudomonas). More on this here.

anaerobic coverage is not needed for pneumonia

- Sometimes there is concern that the patient may have aspirated, so they should be covered for anaerobes.

- The lung is the best oxygenated organ in the body, so it is not very susceptible to anaerobic infection. The only way anaerobic infection can occur is if there is an anatomic disruption that creates a poorly oxygenated compartment (abscess or fluid collection).

- 💡 Anaerobic coverage is indicated only for empyema or lung abscess.

avoid large-volume fluid resuscitation

- Large volume fluid resuscitation may worsen hypoxemic respiratory failure and thereby precipitate the need for intubation.

- Most patients with pneumonia can be stabilized adequately with small-moderate volumes of fluid combined with vasopressors if needed.

- Consider early institution of vasopressors. In many cases, a low-dose vasopressor (e.g. norepinephrine 5-10 mcg/min) may substantially reduce the amount of fluid which is needed to stabilize the patient.

- Fluid should be used only if the following conditions are met:

- Organ hypoperfusion (e.g. poor urine output) or refractory hypotension PLUS

- History and evaluation indicates true volume depletion (as opposed to hypotension which is merely due to vasodilation). Please note that a reduced central venous pressure or collapsed inferior vena cava doesn't necessarily indicate volume depletion, these findings can also be caused by systemic vasodilation.

- Lactate elevation is not a sign of organ malperfusion, nor is it an indication for fluid.

high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC)

- The FLORALI trial suggested improved mortality among patients with severe hypoxemia treated with HFNC.

- HFNC should be considered in patients with significant work of breathing and/or tachypnea. The goal of HFNC is to reduce the work of breathing, and thereby prevent patients from tiring out. In order for this to work, HFNC must be started before the patient is exhausted and in extremis.

- Advantages of HFNC:

- Oxygenation support

- Ventilation support due to dead-space washout

- Humidification may promote secretion clearance

- Doesn't interfere with sputum clearance, coughing, or eating

- Patients may remain on HFNC for several days if needed (often the case for severe lobar pneumonia).

typically avoid BiPAP

- BiPAP doesn't allow patients to clear their secretions. Patients treated on BiPAP often do well initially, but eventually may fail due to retained secretions and mucus plugging.

- BiPAP may be used for limited periods of time to stabilize patients (e.g. for transportation).

- Occasional patients with COPD plus pneumonia may benefit from a rotating schedule of BiPAP and HFNC. Pulmonary toilet and secretion clearance may be performed while the patient is on HFNC.

endotracheal intubation

- This is usually used as a second-line therapy, after trying HFNC.

- Indications for intubation in pneumonia are usually:

- Refractory hypoxemia

- Progressively worsening work of breathing, respiratory exhaustion

steroid should be the default therapy for critically ill patients with CAP

- Several RCTs and meta-analyses have shown that steroid may reduce the length of stay and risk of intubation.(36087797) Consequently, the SCCM/ESICM guidelines currently recommend steroid for patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia.(29090327)

- Whether steroid causes a mortality benefit is unclear, but this is a possibility among the sickest patients. (36942789)

contraindications to steroid

- Paralytic infusion (risk of myopathy).

- Suspicion of pneumonia due to fungus or tuberculosis.

- Severe immunocompromise (e.g., HIV, chemotherapy, neutropenia).

- History of steroid-induced psychosis.

- Patients with non-severe pneumonia who are admitted to ICU for another reason (e.g., delirium, DKA).

patients who might benefit the most

- If the risk/benefit of steroid is unclear, the following factors might support steroid use:

- CRP >150 mg/L indicates a high inflammatory response, which implies greater utility of steroid. (25688779, 36942789)

- Hemodynamic instability (especially higher vasopressor requirements).

- Pneumococcal pneumonia patients might be expected to benefit considerably (based on studies of pneumococcal meningitis).

steroid regimen

- Various regimens have been found to be beneficial. The following are all reasonable:

- Hydrocortisone 50 mg IV q6hrs (may be preferred for patients in shock).

- Prednisone 50 mg PO daily.

- Methylprednisolone 40 mg IV daily.

- Dexamethasone 12 mg once, then 6 mg/day (either PO/IV).

- Relatively short steroid duration is generally sufficient. In the CAPE-COD trial, steroid was tapered off within 8-14 days, depending on whether the patient was improving after four days (figure below). Additionally, steroid therapy was discontinued when patients left the ICU.

pleural effusion management

- Pleural effusion and empyema are common in severe pneumonia.

- Effusion should be evaluated upon admission and every 1-2 days thereafter, using bedside ultrasonography.

management is driven by ultrasonographic features:

- Effusion is small & anechoic (black, without internal echoes) ==> follow with daily ultrasonography, intervene if the effusion expands.

- Effusion is large & anechoic ==> drain effusion dry with thoracentesis.

- Effusion contains septations ==> place pigtail catheter, add tPA/DNAse if complete drainage doesn't occur.

defining treatment failure

- There is no clear definition, but clinical improvement should generally be seen within ~3 days among immunocompetent patients. (34481570)

- Persistent or rising procalcitonin or CRP over several days may be an early sign of treatment failure. (Note, however, that procalcitonin will often rise over the first day or so, even among patients who improve clinically).

- Ongoing deterioration in oxygenation and infiltrates >24 hours after antibiotics is the most concerning feature.

- Radiographic improvement takes weeks, so failure of the radiograph to improve over a few days is expected. Indeed, if the radiograph clears up within 24-48 hours that suggests aspiration pneumonitis, rather than true bacterial pneumonia.

differential diagnosis

- Incorrect initial diagnosis

- Heart failure.

- Pulmonary embolism.

- Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage.

- Organizing pneumonia.

- Eosinophilic pneumonia.

- Bronchoalveolar carcinoma.

- Interstitial lung disease.

- Endobronchial obstruction (leading to atelectasis and/or post-obstructive pneumonia).

- (Further discussion of the differential diagnosis of CAP above: 📖)

- Antibiotic problem:

- Wrong antibiotic, e.g.:

- Multidrug resistant organism.

- Endemic fungal pneumonia or cryptococcus.

- Invasive aspergillosis.

- PJP (pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia).

- Tuberculosis.

- Q-fever or tularemia (may resist azithromycin).

- Inadequate antibiotic dose or penetration into lung tissue.

- Wrong antibiotic, e.g.:

- Intrathoracic complication of pneumonia:

- Lung abscess or necrotizing pneumonia.

- Pleural effusion, e.g.:

- Empyema.

- Large parapneumonic effusion causing respiratory dysfunction.

- Fibroproliferative ARDS.

- Organizing pneumonia (OP).

- Pulmonary superinfection, e.g.:

- Ventilator-associated pneumonia.

- Invasive aspergillus infection in the context of influenza or COVID-19.

- Extrathoracic infection:

- Metastatic infection:

- Endocarditis.

- Meningitis.

- Septic arthritis.

- Line infection (secondary to bacteremia from the pneumonia, or unrelated to the pneumonia).

- C. difficile colitis.

- Metastatic infection:

- Noninfectious complication of hospitalization:

- Iatrogenic volume overload.

- Pulmonary embolism.

- Drug fever.

- Aspiration pneumonitis.

- Atelectasis.

- Cardiovascular complication (e.g., atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction).

- Correct diagnosis and appropriate treatment, with slow resolution:

- Certain pathogens may respond slowly even if treated correctly (e.g., legionella, gram-negative bacteria, Staph. aureus).(35190510)

- Weak host.

approach

- Review all data carefully (especially microbiology).

- CT angiogram of the chest is generally performed to secure the diagnosis of pneumonia and exclude pulmonary embolism or anatomic complication (e.g., abscess or empyema).

- Repeat cultures (blood and sputum).

- HIV screen if not previously performed.

- Bronchoscopy may be considered.

- If a significant pleural effusion is present, it may be drained and sampled.

- Procalcitonin and/or CRP may help sort out infectious vs. noninfectious illness:

- Negative procalcitonin (<0.25 ng/ml) after three days suggests the presence of a non-infectious complication, whereas persistently elevated procalcitonin suggests active infection.

- Among patients with renal insufficiency, C-reactive protein might be used in an analogous fashion (with CRP levels <30 mg/L roughly analogous to a negative procalcitonin).(19762338)

See the chapter on antibiotics, here.

Follow us on iTunes

The Podcast Episode

Want to Download the Episode?

Right Click Here and Choose Save-As

To keep this page small and fast, questions & discussion about this post can be found on another page here.

- Failure to cover for atypical (e.g. treating with piperacillin-tazobactam monotherapy).

- Unnecessary MRSA coverage in patients at low risk for MRSA. In particular, after 48 hours if there is no evidence that the patient has MRSA (e.g. negative nares PCR & negative sputum), then MRSA coverage should be stopped.

- Triaging patients based on their oxygen requirement, while ignoring tachypnea and work of breathing.

- Under-utilization of steroid.

- Missing a pleural effusion which develops insidiously after admission.

- Egregiously weird antibiotic regimens for patients with dubious penicillin allergy. 📖

- Giving clindamycin for anaerobic coverage.

- Double-coverage of pseudomonas.

- Dumping 30 cc/kg fluid into a sick pneumonia patient on the verge of intubation because the lactate is elevated.

Guide to emoji hyperlinks

= Link to online calculator.

= Link to Medscape monograph about a drug.

= Link to IBCC section about a drug.

= Link to IBCC section covering that topic.

= Link to FOAMed site with related information.

= Link to supplemental media.

References

- 17452932 Rodríguez A, Mendia A, Sirvent JM, Barcenilla F, de la Torre-Prados MV, Solé-Violán J, Rello J; CAPUCI Study Group. Combination antibiotic therapy improves survival in patients with community-acquired pneumonia and shock. Crit Care Med. 2007 Jun;35(6):1493-8. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000266755.75844.05 [PubMed]

- 17573487 Rice TW, Wheeler AP, Bernard GR, Hayden DL, Schoenfeld DA, Ware LB; National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute ARDS Network. Comparison of the SpO2/FIO2 ratio and the PaO2/FIO2 ratio in patients with acute lung injury or ARDS. Chest. 2007 Aug;132(2):410-7. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0617 [PubMed]

- 18513176 Cretikos MA, Bellomo R, Hillman K, Chen J, Finfer S, Flabouris A. Respiratory rate: the neglected vital sign. Med J Aust. 2008 Jun 2;188(11):657-9. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01825.x [PubMed]

- 19762338 Menéndez R, Martinez R, Reyes S, Mensa J, Polverino E, Filella X, Esquinas C, Martinez A, Ramirez P, Torres A. Stability in community-acquired pneumonia: one step forward with markers? Thorax. 2009 Nov;64(11):987-92. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.118612 [PubMed]

- 19789456 Brown SM, Jones BE, Jephson AR, Dean NC; Infectious Disease Society of America/American Thoracic Society 2007. Validation of the Infectious Disease Society of America/American Thoracic Society 2007 guidelines for severe community-acquired pneumonia. Crit Care Med. 2009 Dec;37(12):3010-6. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b030d9 [PubMed]

- 21048054 Ison MG, Lee N. Influenza 2010-2011: lessons from the 2009 pandemic. Cleve Clin J Med. 2010 Nov;77(11):812-20. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.77a.10135 [PubMed]

- 21865188 Chalmers JD, Taylor JK, Mandal P, Choudhury G, Singanayagam A, Akram AR, Hill AT. Validation of the Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoratic Society minor criteria for intensive care unit admission in community-acquired pneumonia patients without major criteria or contraindications to intensive care unit care. Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Sep;53(6):503-11. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir463 [PubMed]

- 22247123 Wunderink RG, Niederman MS, Kollef MH, Shorr AF, Kunkel MJ, Baruch A, McGee WT, Reisman A, Chastre J. Linezolid in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nosocomial pneumonia: a randomized, controlled study. Clin Infect Dis. 2012 Mar 1;54(5):621-9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir895 [PubMed]

- 24798841 Jones Q, Benamore R, Fryer E, Sykes A. A 50-year-old man with a cough and painful chest wall mass. Chest. 2014 May;145(5):1158-1161. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-2039 [PubMed]

- 24893087 Mortensen EM, Halm EA, Pugh MJ, Copeland LA, Metersky M, Fine MJ, Johnson CS, Alvarez CA, Frei CR, Good C, Restrepo MI, Downs JR, Anzueto A. Association of azithromycin with mortality and cardiovascular events among older patients hospitalized with pneumonia. JAMA. 2014 Jun 4;311(21):2199-208. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.4304 [PubMed]

- 26859379 Bender MT, Niederman MS. Improving outcomes in community-acquired pneumonia. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2016 May;22(3):235-42. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000257 [PubMed]

- 27418577 Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, et al. Management of Adults With Hospital-acquired and Ventilator-associated Pneumonia: 2016 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Sep 1;63(5):e61-e111. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw353 [PubMed]

- 28702467 Cosimi RA, Beik N, Kubiak DW, Johnson JA. Ceftaroline for Severe Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infections: A Systematic Review. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017 May 2;4(2):ofx084. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofx084 [PubMed]

- 29090327 Pastores SM, Annane D, Rochwerg B; Corticosteroid Guideline Task Force of SCCM and ESICM. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of critical illness-related corticosteroid insufficiency (CIRCI) in critically ill patients (Part II): Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) 2017. Intensive Care Med. 2018 Apr;44(4):474-477. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4951-5 [PubMed]

- 29090992 Ramadurai D, Kelmenson DA, Smith J, Dee E, Northcutt N. Progressive Dyspnea and Back Pain after Complicated Pneumonia. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017 Nov;14(11):1714-1717. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201703-256CC [PubMed]

- 29119848 Athlin S, Lidman C, Lundqvist A, Naucler P, Nilsson AC, Spindler C, Strålin K, Hedlund J. Management of community-acquired pneumonia in immunocompetent adults: updated Swedish guidelines 2017. Infect Dis (Lond). 2018 Apr;50(4):247-272. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2017.1399316 [PubMed]

- 29147471 Karki A, Thurm C, Cervellione K. Experience with ceftaroline for treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia in a community hospital. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2017 Oct 18;7(5):300-302. doi: 10.1080/20009666.2017.1374107 [PubMed]

- 29609223 Williams JM, Greenslade JH, Chu KH, et al. Utility of community-acquired pneumonia severity scores in guiding disposition from the emergency department: Intensive care or short-stay unit? Emerg Med Australas. 2018 Aug;30(4):538-546. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12947 [PubMed]

- 29968985 Lee MS, Oh JY, Kang CI, Kim ES, Park S, Rhee CK, Jung JY, Jo KW, Heo EY, Park DA, Suh GY, Kiem S. Guideline for Antibiotic Use in Adults with Community-acquired Pneumonia. Infect Chemother. 2018 Jun;50(2):160-198. doi: 10.3947/ic.2018.50.2.160 [PubMed]

- 30118377 Garnacho-Montero J, Barrero-García I, Gómez-Prieto MG, Martín-Loeches I. Severe community-acquired pneumonia: current management and future therapeutic alternatives. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2018 Sep;16(9):667-677. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2018.1512403 [PubMed]

- Walker C & Chung JH (2019). Muller’s Imaging of the Chest: Expert Radiology Series. Elsevier.

- Shepard, JO. (2019). Thoracic Imaging The Requisites (Requisites in Radiology) (3rd ed.). Elsevier.

- 30838060 Natali D, Tran Pham H, Nguyen The H. A Vietnamese woman with a 2-week history of cough. Breathe (Sheff). 2019 Mar;15(1):55-59. doi: 10.1183/20734735.0256-2018 [PubMed]

- 30844921 Krutikov M, Rahman A, Tiberi S. Necrotizing pneumonia (aetiology, clinical features and management). Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2019 May;25(3):225-232. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000571 [PubMed]

- 32101906 Gil R, Webb BJ. Strategies for prediction of drug-resistant pathogens and empiric antibiotic selection in community-acquired pneumonia. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2020 May;26(3):249-259. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000670 [PubMed]

- 32127438 Modi AR, Kovacs CS. Community-acquired pneumonia: Strategies for triage and treatment. Cleve Clin J Med. 2020 Mar;87(3):145-151. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.87a.19067 [PubMed]

- 32805298 Nair GB, Niederman MS. Updates on community acquired pneumonia management in the ICU. Pharmacol Ther. 2021 Jan;217:107663. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107663 [PubMed]

- 33405483 Martin-Loeches I, Torres A. New guidelines for severe community-acquired pneumonia. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2021 May 1;27(3):210-215. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000760 [PubMed]

- 34481570 Aliberti S, Dela Cruz CS, Amati F, Sotgiu G, Restrepo MI. Community-acquired pneumonia. Lancet. 2021 Sep 4;398(10303):906-919. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00630-9 [PubMed]

- 35190510 Martin-Loeches I, Garduno A, Povoa P, Nseir S. Choosing antibiotic therapy for severe community-acquired pneumonia. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2022 Apr 1;35(2):133-139. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000819 [PubMed]

- 35404672 Rothberg MB. Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Ann Intern Med. 2022 Apr;175(4):ITC49-ITC64. doi: 10.7326/AITC202204190 [PubMed]

- 36942789 Dequin PF, Meziani F, Quenot JP, Kamel T, Ricard JD, Badie J, Reignier J, Heming N, Plantefève G, Souweine B, Voiriot G, Colin G, Frat JP, Mira JP, Barbarot N, François B, Louis G, Gibot S, Guitton C, Giacardi C, Hraiech S, Vimeux S, L'Her E, Faure H, Herbrecht JE, Bouisse C, Joret A, Terzi N, Gacouin A, Quentin C, Jourdain M, Leclerc M, Coffre C, Bourgoin H, Lengellé C, Caille-Fénérol C, Giraudeau B, Le Gouge A; CRICS-TriGGERSep Network. Hydrocortisone in Severe Community-Acquired Pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2023 Mar 21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2215145 [PubMed]