CONTENTS

- Introduction

- Epidemiology

- Triggers & associated conditions

- Clinical features

- Diagnosis

- Management

- Prognosis

- Related topics:

- Podcast

- Questions & discussion

- Pitfalls

basics of Reversible Cerebral Vasoconstriction Syndrome (RCVS)

- RCVS typically presents with thunderclap headache due to diffuse cerebral vasospasm. RCVS is usually benign, but can cause severe sequelae (most notably, ischemic strokes).

- Historically, RCVS has been known as numerous other entities, some of which are listed here:(31272323)

- Thunderclap headache with reversible vasospasm.

- Benign angiopathy of the central nervous system.

- Postpartum cerebral angiopathy.

- Migrainous vasospasm, or migraine angiitis.

- Drug-induced cerebral arteritis or angiopathy.

- Call-Fleming syndrome.

- It is only recently that these varied presentations have been unified under the rubric of RCVS. The ability to diagnose vasospasm noninvasively, by using either CT or MR angiography, has dramatically advanced the field. With a clearer concept of RCVS and improved diagnostic tools, it's likely that RCVS will be diagnosed more often in the future.

pathophysiology

- The primary problem seems to be diffuse, multifocal vasospasm of intracranial arteries. This may start with the smaller distal vessels and progress proximally to the larger arteries.

- The cause isn't clear, but it may relate to autonomic hyperactivity and/or endothelial dysfunction.(29274685) Histology does not reveal any inflammatory or vasculitic process.

- The pathogenesis of the thunderclap headache is unclear. It's conceivable that this results from a positive feed-forward cycle involving increasing pain, increasing sympathetic tone, and increasing vasospasm due to innervation of arteries via the first division of the trigeminal nerve (V1). In some cases, thunderclap headache may reflect the occurrence of a convexity subarachnoid hemorrhage caused by RCVS.

- Women are more commonly affected than men (with ratios ranging from 2:1 to 10:1).

- The average age is ~40 years old. RCVS occurs predominantly between the ages of 20-50, being reported up to 76 years old.(28456915)

- Though relatively uncommon, RCVS is probably more common than previously recognized (due to underdiagnosis). This may be especially true in the ICU, where RCVS may occur as a complication of other neurological conditions (especially PRES).

- Migraines and antimigraine therapies (e.g., triptans, ergot derivatives, isometheptene).(34618761)

- Pregnancy, (pre)eclampsia, postpartum (up to six weeks), ovarian stimulation, oral contraceptive medications, anastrozole.

- Medications:

- Antidepressants (e.g., SSRIs, SNRIs).

- Adrenergic agents:

- Alpha-agonists (e.g., pseudoephedrine, phenylpropanolamine, nasal decongestants, midodrine, phenylephrine).

- Epinephrine.

- Amphetamine derivatives.

- Atovaquone.(34618761)

- Bromocriptine.(34618761)

- Cabergoline.(34618761)

- Chemotherapeutics & immunomodulators (e.g., cyclophosphamide, tacrolimus, cytarabine, fingolimod, etanercept, tocilizumab).(34618761)

- Ergot derivatives (ergotamine tartrate, methergine, methylergonovine).

- Erythropoietin.(34618761)

- Nicotine patches.(34618761)

- NSAIDs. (29274685)

- Interferon alfa.(34618761)

- Blood transfusion, intravenous immune globulin (IVIG).

- Withdrawal from nifedipine or caffeine.

- Illicit substances (e.g., sympathomimetics, marijuana, LSD).

- Hypercalcemia.

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).(34618761)

- Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP).(34618761)

- Trauma (head trauma, neurosurgery).

- Secondary complication of other cerebrovascular disease:

thunderclap headache

- ⚡️95% of patients present with a severe headache that reaches maximum intensity within a minute, although onset can be more gradual. Pain often improves within 1-3 hours, which helps differentiate this from subarachnoid hemorrhage.

- Headaches may be triggered by exertion, emotion, sex, swimming, bathing/showering, or Valsalva maneuvers (coughing, sneezing, defecation).

- Associated features may include nausea and vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia, and visual changes. Pain may be so severe as to cause screaming and collapse.(29274685)

- Headaches in RCVS tend to recur within days to weeks.(28456915) A history of multiple thunderclap headaches recurring over several days is nearly pathognomonic for the diagnosis of RCVS.⚡️⚡️⚡️⚡️

- RCVS is the most common cause of true thunderclap headache (pain reaching maximal severity in <1 minute) in patients without aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage.(28456915, 29274685)

- More on thunderclap headaches: 📖

subsequent neurological sequelae

- >90% of RCVS patients ultimately have a benign course. However, most patients may experience one of the following neurological sequelae. These typically evolve within 1-2 weeks of the initial headache, as vasospasm continues to intensify. Clinical symptoms will vary widely, depending on which sequelae occur (e.g., ischemic strokes may cause focal neurological deficits). Hemorrhages and seizures usually occur within a week of onset, whereas ischemic complications occur after 2-3 weeks.(29274685)

- Convexity subarachnoid hemorrhage (~33%).

- These hemorrhages are typically small and self-limited, located near the vertex of the head. However, there is a risk that hemorrhage could cause thrombosis of nearby cortical veins.(31761061)

- In some cases, a convexity SAH provides a key clue which helps reveal the diagnosis of RCVS.

- Watershed ischemic strokes (~~15%).

- These most often occur in cortical/subcortical regions in a symmetric distribution along arterial watershed areas, between the anterior and posterior circulation.

- If infarcts are seen within the anterior or posterior cerebral artery territories, this may suggest a concomitant cervical artery dissection which warrants additional investigation.(28456915)

- Intraparenchymal hemorrhages (~10%). These are usually small and lobar.

- Seizures (~5%).(34618761)

noncontrast CT scan

- CT imaging is often initially normal. However, CT scan may detect complications of RCVS:

- (1) Lobar intracerebral hemorrhage.

- (2) Convexity subarachnoid hemorrhage.

- 💡RCVS is the most common cause of cortical surface (convexity) subarachnoid hemorrhage in patients <60 years old. More on the differential diagnosis of convexity SAH here.

- (3) Ischemic infarction.

- (4) Rarely, subdural hematoma.

CT angiography (CTA)

- CTA is often the initial test of choice for RCVS (e.g., patients presenting with thunderclap headache). CTA can be performed emergently, rapidly excluding more dangerous diagnostic possibilities such as aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Some centers routinely include CT angiography of the neck as well, given an association between RCVS and cervical neck dissection.(29274685)

- The characteristic finding on CT angiography is smooth, tapered vasoconstriction that is followed by abnormally dilated segments (a “string of beads” pattern). Vasoconstriction is widespread and bilateral. The differential diagnosis of beaded vessels includes vasospasm following subarachnoid hemorrhage, primary angiitis of the central nervous system, and intracranial atherosclerosis.(29274685)

- CT angiography has a sensitivity of 80% when compared to invasive angiography (the gold standard, which is rarely used as a first-line study).(31272323) CT angiography may be normal at the time of initial presentation, only revealing vasoconstriction >3-5 days later. Vasoconstriction is often maximal about two weeks after the initial symptoms.(29274685)

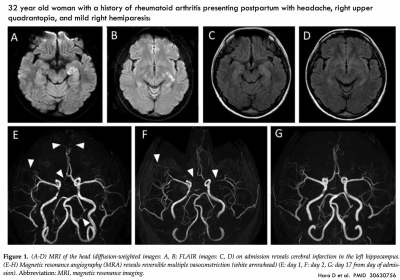

MRI

- Similar to noncontrast CT scanning, about half of MRI scans may be normal initially.(28456915)

- MRI may show vasogenic edema (T2/FLAIR hyperintensity) that is symmetrically distributed in a watershed distribution (similar to abnormalities seen in PRES).

- Hyperintense vessels (“dot sign”) on FLAIR imaging may be caused by slow blood flow through dilated blood vessels.(31272323)

- This is seen in ~20% of patients with RCVS.

- Hyperintense vessels correlate with impaired blood flow and development of clinical complications (PRES and ischemic stroke).

- This may be a very early finding, which is observed before spasm of the larger vessels becomes evident on angiography.(31272323)

- The differential diagnosis of the “dot sign” includes leptomeningeal carcinomatosis, meningitis, and status epilepticus.(29274685)

- MRI may show the complications of RCVS (e.g., lobar intracerebral hemorrhage, convexity subarachnoid hemorrhage, ischemic infarction, and rarely subdural hematoma).

MR angiography (MRA)

- MR angiography (MRA) has a similar performance compared to CT angiography, with a sensitivity of ~80% compared to invasive angiography.(31272323)

- MRA may have the added benefit of evaluating for cervical artery dissection, which may occur simultaneously with RCVS. However, this requires specifically ordering a cervical MRA and protocoling the study appropriately. Cervical MRA may often require intravenous contrast, unlike an isolated MRA of the brain (which may often be done without intravenous contrast, by using time-of-flight MRI techniques to detect flowing blood).

digital subtraction angiography (invasive angiography)

- Invasive angiography is the gold standard diagnostic test, but it is less commonly used in clinical practice. In the context of RCVS, angiography may carry a 9% risk of provoking ischemia.(29274685)

- It is generally unnecessary to immediately reach diagnostic certainty regarding RCVS (because >90% of patients will improve spontaneously and because there are no proven therapies for RCVS). Thus, it may be safer to tolerate some diagnostic uncertainty and perform a repeat CTA or MRA (rather than proceeding immediately to invasive angiography).

- Invasive angiography may offer the ability to perform angioplasty or local administration of vasodilators. However, neither of these therapies is proven to cause clinical improvement. Excess vasodilation could increase the risk of hemorrhagic transformation or reperfusion injury.(34618761)

- Indications for invasive angiography might include progressive clinical deterioration despite conservative management, or an inability to exclude aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage.

lumbar puncture

- Lumbar puncture is generally normal or near-normal in RCVS, but this may be required to exclude alternative diagnoses.

- Elevated protein may be seen in ~15% of patients.(34879501) Based on International Headache Society criteria, protein <80 mg/dL and leukocytes <10-15/uL are consistent with RCVS.(Louis 2021)

- Although RCVS can cause small subarachnoid hemorrhages along the cortical surface, RCVS doesn't cause the lumbar puncture findings which are seen in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (e.g., xanthochromia and elevated erythrocytes).

identification & avoidance of potential RCVS triggers

- See the list of triggers above. Be sure to perform a thorough review of all medications (prescribed, over-the-counter, and illicit).

- Valsalva maneuvers may trigger headaches, so an aggressive bowel regimen may be considered (e.g. with oral magnesium preparations, as discussed further below).

possible indications for ICU admission

- Observation in patients with severe angiographic abnormalities.

- Patients with focal ischemic strokes, intracranial hemorrhages, or seizure.

- 💡 >90% of patients will improve spontaneously, so conservative therapy is appropriate for nearly all patients.

analgesia

- Opioid analgesia may be required. If so, an aggressive bowel regimen should be used to avoid constipation (which may lead to Valsalva maneuvers, which can worsen RCVS).

- Adjunctive acetaminophen may be beneficial.

- ⚠️ NSAIDs may be undesirable in the context of a risk of intracranial hemorrhage. Furthermore, NSAIDs have been implicated in causing RCVS.(28456915)

blood pressure management

- There is no high-quality data regarding optimal blood pressure management.

- Hypotension:

- Probably detrimental, as this might increase the risk of ischemic stroke.(33896537)

- Management should involve ensuring a state of euvolemia.

- Note that vasopressors could exacerbate RCVS – so these may not be desirable.

- Hypertension:

- If severe, treatment may be considered. Additionally, lower blood pressure targets may be appropriate in patients with coexisting PRES.(33896537)

- Ensure that pain is adequately treated, as this may be a contributing factor to hypertension.

- Nimodipine or a calcium channel blocker might be the agent of choice, given some possibility that this may improve vasospasm of the smaller vessels.

vasodilators

- No high-quality data exists, which does not allow any strong recommendations to be made.

- Some reported cases suggest a benefit from 2-4 grams of IV magnesium sulfate, which may be reasonable (especially among patients with low magnesium levels).(27366294) This can be followed by oral magnesium as a maintenance therapy.

- Nimodipine was not found to improve vasospasm in two prospective case series. Given that hypotension could aggravate brain perfusion, the value of nimodipine is not clearly defined (aside from patients with severe hypertension who need an antihypertensive medication). However, calcium channel blockers such as nimodipine and verapamil are routinely used in many centers in an effort to relieve vasoconstriction and headaches.(34618761) These are generally discontinued once symptoms improve, although some centers continue their use for up to 30 days.

- Intra-arterial vasodilation and angioplasty by neurointerventional radiology may be considered in severe and progressive cases.

seizure management

- Seizure prophylaxis isn't indicated.

- Seizures should be treated as per usual regimens.📖

- Most patients will do well. Cerebral vasoconstriction will resolve over time (hence the name reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome). Unfortunately, parenchymal damage due to ischemia or hemorrhage may not always resolve.

- Progressive vasoconstriction can occur in <5% of patients (leading to large ischemic strokes). This may be more common among postpartum women.

- Following resolution, recurrent RCVS is very uncommon.

basics

- PACNS affects the small/medium-sized arteries of the brain, spinal cord, and/or leptomeninges. However, spinal cord manifestations alone are rare.(33832773)

- PACNS is exceedingly rare. When PACNS is suspected, it's usually not the correct final diagnosis.

- The entity of PACNS in the medical literature is ambiguous:

- (1) Many studies and case reports lack histopathological confirmation, implying that much of the literature may not truly be describing patients with PACNS.

- (2) Histopathologic findings in PACNS are variable (e.g., including both granulomatous and lymphocytic vasculitis). Thus, it's likely that the entity of PACNS actually is a conglomeration of a several distinct pathophysiologic conditions.

clinical presentation

- Presentation is extremely variable:

- Acute presentations are uncommon, but possible.

- Symptoms vary depending on various structures involved (including the brain, spinal cord, and cranial nerves).

- Untreated PACNS will progress, so stability over several months argues against this diagnosis.

- Some more frequent presentations:(31649101)

- A multiple sclerosis mimic with relapsing-remitting symptoms that may include optic neuropathy and brainstem involvement. Features that may differentiate this from multiple sclerosis include seizures, encephalopathic episodes, severe and persistent headaches, or hemispheric stroke-like episodes.

- Stroke(s). The diagnosis of PACNS may be suggested by multifocal strokes occurring in younger patients without vascular risk factors.

- Intracranial mass lesions with headache, focal signs, drowsiness, and often elevated intracranial pressure.

- Encephalopathy (commonly presenting as an acute confusional state, which may progress to coma.)

- Headache is common (usually subacute, with gradual onset).

- Systemic inflammation can be present (e.g., fever, night sweats).

epidemiology

- Reported cases suggest a 2:1 male predominance.

- The age range of affected patients is broad, but it would be less common to encounter among patients <30 years old or >70 years old.(24198904)

general laboratory testing

- ESR and CRP are usually normal or slightly elevated in PACNS. (Louis 2021)

lumbar puncture

- Abnormal in ~80% of patients.(31649101)

- The primary role of lumbar puncture is exclusion of alternative possibilities (especially infection).

- The most common pattern seen in PACNS is moderate lymphocytic pleocytosis, elevated protein, and normal glucose levels (a “viral meningitis” pattern).

- Normal CSF findings, or pleocytosis >250 cells/uL, would argue against a diagnosis of PACNS.(33832773)

neuroimaging

- MRI is abnormal in >90% of patients.(31649101)

- Potential findings include:

- Multiple infarcts may be seen, across several arterial territories.

- Small-vessel ischemic demyelination causing multifocal white matter lesions.

- Tumor-like lesions.

- Leptomeningeal enhancement.

- Subarachnoid or intraparenchymal hemorrhages, and/or multiple microhemorrhages.

vascular imaging

- Vascular imaging classically may show multifocal narrowing with areas of dilation/beading.

- Diagnostic performance is extremely poor. When using histopathology as a gold-standard, invasive angiography may have a sensitivity of ~50% and a specificity of ~30%.(31649101)

- ⚠️ Given the low specificity of vascular imaging and the rarity of PACNS, most patients found to have vasculitic changes suggestive of PACNS will actually not have PACNS! Other causes of vasculitic changes on angiography are listed below (many of which are far more common than PACNS):(31649101)

- Intracranial atherosclerosis.

- RCVS (reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome).

- Migraine.

- VZV arteritis syndromes.

- Multiple cerebral emboli (e.g., due to endocarditis).

- Vasospasm (e.g., drug-related, following subarachnoid hemorrhage).

- Intracerebral hematoma.

- Acute trauma.

- Severe hypertension.

- Antiphospholipid syndrome.

- Fibromuscular dysplasia, Marfan's syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndromes.

- Intravascular lymphoma.

- Moyamoya disease.

- CADASIL (cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy).

- Radiation vasculopathy.

- Sickle cell disease.

- Systemic vasculitis.

- With improvements in noninvasive vascular imaging, it's less likely that invasive angiography will provide additional information beyond CT/MR angiography.(31649101)

brain biopsy

- Tissue diagnosis is generally required to reach a secure diagnosis. In the absence of biopsy confirmation, PACNS is likely to be overdiagnosed.(33832773)

- Biopsy provides ~75% of patients with a diagnosis (in some cases an unsuspected one).(31649101)

management

- There is no high-quality evidence regarding management. Some management strategies have been borrowed from the treatment of granulomatosis with polyangiitis.(24198904)

- Steroid is often started at 1 mg/kg with a gradual taper. However, pulse-dose steroids may be utilized among patients with fulminant PACNS.

- Steroid-sparing immunosuppressive medications are needed as well, such as cyclophosphamide. However, cyclophosphamide should generally be restricted to patients whose diagnosis has been proven on tissue biopsy. (Louis 2021)

Follow us on iTunes

To keep this page small and fast, questions & discussion about this post can be found on another page here.

- Beware of misdiagnosing RCVS as a migraine headache, because some of the treatments for migraine (particularly triptans) may exacerbate RCVS.

- RCVS may coexist with cervical artery dissection, so patients with RCVS and neck pain require further evaluation for cervical artery dissection.(28456915)

Acknowledgement: Thanks to Dr. Richard Choi (@rkchoi) for thoughtful comments on this chapter.

Guide to emoji hyperlinks

= Link to online calculator.

= Link to Medscape monograph about a drug.

= Link to IBCC section about a drug.

= Link to IBCC section covering that topic.

= Link to FOAMed site with related information.

= Link to supplemental media.

References

- 24198904 Kriseman YL, Lee H, Chung S, Josephson SA. A 67-year-old man with headaches, gait changes, and altered mental status. Neurohospitalist. 2013 Oct;3(4):221-7. doi: 10.1177/1941874413483756 [PubMed]

- 27366294 Mijalski C, Dakay K, Miller-Patterson C, Saad A, Silver B, Khan M. Magnesium for Treatment of Reversible Cerebral Vasoconstriction Syndrome: Case Series. Neurohospitalist. 2016 Jul;6(3):111-3. doi: 10.1177/1941874415613834 [PubMed]

- 28456915 Cappelen-Smith C, Calic Z, Cordato D. Reversible Cerebral Vasoconstriction Syndrome: Recognition and Treatment. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2017 Jun;19(6):21. doi: 10.1007/s11940-017-0460-7 [PubMed]

- 29274685 Arrigan MT, Heran MKS, Shewchuk JR. Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome: an important and common cause of thunderclap and recurrent headaches. Clin Radiol. 2018 May;73(5):417-427. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2017.11.017 [PubMed]

- 31272323 Burton TM, Bushnell CD. Reversible Cerebral Vasoconstriction Syndrome. Stroke. 2019 Aug;50(8):2253-2258. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.024416 [PubMed]

- 31649101 Rice CM, Scolding NJ. The diagnosis of primary central nervous system vasculitis. Pract Neurol. 2020 Apr;20(2):109-114. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2018-002002 [PubMed]

- 32487899 O'Neal MA. Obstetric and Gynecologic Disorders and the Nervous System. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2020 Jun;26(3):611-631. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000860 [PubMed]

- 33832773 Kraemer M, Berlit P. Primary central nervous system vasculitis – An update on diagnosis, differential diagnosis and treatment. J Neurol Sci. 2021 May 15;424:117422. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2021.117422 [PubMed]

- 33896537 Macri E, Greene-Chandos D. Neurological Emergencies During Pregnancy. Neurol Clin. 2021 May;39(2):649-670. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2021.02.008 [PubMed]

- 34618761 Singhal AB. Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome and Reversible Cerebral Vasoconstriction Syndrome as Syndromes of Cerebrovascular Dysregulation. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2021 Oct 1;27(5):1301-1320. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000001037 [PubMed]

- 34879501 Spadaro A, Scott KR, Koyfman A, Long B. Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome: A narrative review for emergency clinicians. Am J Emerg Med. 2021 Dec;50:765-772. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2021.09.072 [PubMed]

- Louis ED, Mayer SA, Noble JM. (2021). Merritt’s Neurology (Fourteenth). LWW.