CONTENTS

- Rapid Reference 🚀

- Preamble & disclaimer

- Diagnosis

- Therapeutic target (CIWA vs RASS)

- Treatment: Phenobarbital monotherapy

- Alternative agents

- Special situations

- Podcast

- Questions & discussion

- Pitfalls

evaluation

- History

- Pattern (daily vs. binge)?

- Timing of last drink?

- History of withdrawal with alcohol cessation?

- Labs

- STAT fingerstick glucose.

- Electrolytes including Ca/Mg/Phos.

- CBC with differential, INR, PTT, liver function tests.

- Imaging

- Chest X-ray.

- Consider CT head to exclude subdural hematoma.

typical treatment

- Phenobarbital:

- Dose-titration strategy for most patients as below 👇.

- If patient has had a withdrawal seizure: Rapidly escalate to a cumulative dose of at least 15 mg/kg phenobarbital if mental status allows, consider adding pyridoxine 100 mg IV/PO.

- Thiamine:

- If altered mental status & Wernicke encephalopathy is possible: 500 mg IV q8hr.

- If normal mental status: 100 mg IV daily to prevent Wernicke encephalopathy.

- Nutritional & electrolyte deficiencies:

- Consider risk of refeeding syndrome and monitor/prophylax for this as appropriate.

- Magnesium repletion is often needed.

- Phosphate repletion is often needed.

There are numerous (perhaps innumerable) reasonable ways to treat alcohol withdrawal. Prior to the ~1970s, barbiturates were front-line agents. Following a push by pharma to market newly developed benzodiazepines, this shifted to benzodiazepines. This transition wasn't based upon any evidence that benzodiazepines deserved to be front-line agents, but rather perhaps the perception that benzodiazepines were newer and therefore must be better. Currently, the pendulum is swinging back to barbiturates. This chapter presents a barbiturate-monotherapy strategy for most patients, which is supported by a growing body of evidence.(36788902)

accurate alcohol history

- History is the most important component of the diagnosis.

- The electronic medical record may list “alcoholism” years after the patient has quit drinking. Whenever possible, documentation in the record should be verified. It may be necessary to get collateral information from friends or family (even if this means calling them in the middle of the night).

- Key historical elements:

- How much does the patient drink?

- Pattern of drinking (daily versus binge drinking)?

- Does the patient withdraw when they stop drinking?

- Is there a history of withdrawal seizures, delirium tremens, or intubation?

- (Admission blood alcohol level)

- For patients who are altered and cannot provide an accurate history, admission blood alcohol level may provide some objective evidence regarding active alcohol use. The risk of withdrawal is especially high among patients with an admission alcohol level >200 mg/dL.(32794143)

timing & potential components of withdrawal

- Timing is the second most important aspect of the diagnosis.

- Symptomatic withdrawal can begin as soon as 6 hours after cessation of alcohol.(32794143)

- Common symptoms include anxiety, nausea, and mild tremors.

- Alcoholic hallucinosis often occurs ~8-12 hours after alcohol cessation.(32256131)

- This involves hallucinations (usually visual) without frank delirium.

- Aside from hallucinations, patients have a clear sensorium.

- Alcohol withdrawal seizures usually occur ~12-48 hours after alcohol cessation. Further discussion below: 📖

- Delirium tremens (aka, alcohol withdrawal delirium) usually occurs within a window of ~2-4 days after alcohol cessation.

- Delirium beginning >4 days into the hospital course is more likely to have a non-alcohol related etiology (e.g. sepsis, polypharmacy, sleep deprivation).

clinical features of alcohol withdrawal often include:

- Autonomic activation:

- Hypertension.

- Tachycardia.

- Diaphoresis.

- Low-grade fever.

- Neurologic:

- Anxiety, insomnia.

- Hyperreflexia.

- Diffuse tremor.

- Alcoholic hallucinosis

- Seizures.

- Delirium tremens.

- Other:

- Nausea, vomiting.

- Headache.

consider other possibilities

- Delirium tremens is a diagnosis of exclusion, so consider other causes of agitated delirium (hypoglycemia, infection, etc.).

- For differential diagnosis & evaluation, see the chapter on delirium.

- Some clues that the patient doesn't have delirium tremens:

- 🔎 Patient becomes somnolent following moderate-low doses of benzodiazepine (patients with real delirium tremens are benzodiazepine-resistant).

- 🔎 Patient remains agitated despite >15 mg/kg phenobarbital (this is usually effective for alcohol withdrawal).

- 🔎 Delirium occurs, without other features of delirium tremens (e.g., absence of hypertension or tremors).

other neurological disorders associated with alcoholism

- Hepatic encephalopathy.

- Wernicke encephalopathy.

- SESA syndrome (subacute encephalopathy with seizures in alcoholics). 📖

- Marchiafava-Bignami disease (demyelination of the corpus callosum).

- Osmotic demyelination syndrome (ODS).

alcohol withdrawal vs. hepatic encephalopathy

Occasionally, in a patient with cirrhosis due to alcoholism there will be a question of sorting out hepatic encephalopathy versus alcohol withdrawal. These are fundamentally nearly opposite pathologies:

⚠️ Be careful about over-diagnosing patients with alcohol withdrawal, because the treatment for alcohol withdrawal can be disastrous in a patient who actually has hepatic encephalopathy:

- Patients with hepatic encephalopathy have excess GABA stimulation, so they are very sensitive to GABAergic medications (e.g., benzodiazepines or barbiturates).

- Administration of benzodiazepines or barbiturates to a patient with hepatic encephalopathy risks inducing a prolonged comatose state.

- ⚠️ Hepatic encephalopathy is a strong contraindication to phenobarbital.

some general rules of thumb:

- The more advanced the liver disease is, the more likely the patient is to have hepatic encephalopathy.

- For patients with a history of hepatic encephalopathy, be very cautious about making a diagnosis of alcohol withdrawal.

CIWA is a complex score which can be used to monitor and titrate therapy for alcohol withdrawal. CIWA scoring has several drawbacks, and generally isn't very useful (especially within a critical care arena, which is staffed by experienced nurses).

- CIWA is extremely effort-intensive.

- CIWA can be affected by a wide variety of abnormalities which may be impacted by other physiologic derangement (e.g., tachycardia due to atrial fibrillation).

- Due to the multitude of factors composing a CIWA scale, it can be difficult to determine precisely what a specific CIWA score means (similar to the total Glasgow Coma Scale).

The preferred therapeutic target for medication titration in the Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale (RASS) as shown below. This is simpler and more reproducible. The use of a RASS score as the therapeutic target for dosing phenobarbital was validated by Oks et al.(29925291)

Although RASS score is better than CIWA, no tool can replace bedside assessment by an experienced clinician. When in doubt about whether the patient truly has alcohol withdrawal symptoms, the patient should be thoughtfully re-assessed.

Although RASS score is better than CIWA, no tool can replace bedside assessment by an experienced clinician. When in doubt about whether the patient truly has alcohol withdrawal symptoms, the patient should be thoughtfully re-assessed.

Phenobarbital has a very simple pharmacology, which is well suited to treat alcohol withdrawal.

half-life

- Perhaps the most notable aspect of phenobarbital is its long half-life (~3-4 days).

- Doses that are administered over the course of 1-2 days will accumulate. The goal of giving additional doses is to gradually up-titrate the total body phenobarbital level to a therapeutic concentration.

- This is different from most drugs (e.g. lorazepam), where repeated doses are needed to maintain a stable drug level.

relationship of dose to drug levels

- The drug level is a linear function of the amount of phenobarbital administered.

- A predictable linear relationship allows weight-based doses to reproducibly achieve therapeutic drug levels.

- The volume of distribution is ~0.65 L/kg.(7068937, 3973064) This allows the serum level to be estimated from the administered dose using the formula below. Some limitations of this formula:

- The cumulative dose should be administered within <48 hours (if administered over a longer time, then significant metabolism may occur).

- The impact of severe obesity remains unclear.

interpretation of drug levels

- Phenobarbital levels may be roughly interpreted as shown above.

- One important caveat is that phenobarbital is synergistic with benzodiazepine, so toxicity could occur at lower phenobarbital levels in the presence of benzodiazepine.

- These pharmacokinetics demonstrate why it is impossible for a dose of 10 mg/kg phenobarbital to cause a toxic phenobarbital level:

- 10 mg/kg will yield a drug level of ~15 ug/mL, which is more than four times lower than levels which will cause severe toxicity.

- Please note that 10 mg/kg phenobarbital could tip over a patient who is on the borderline of obtundation due to other causes (e.g. benzodiazepines, head trauma, etc.). However, 10 mg/kg phenobarbital alone given in a patient with uncomplicated alcohol withdrawal should be very safe.

routes of administration

- Phenobarbital can be given intravenously, intramuscularly, or orally. All routes achieve ~100% bioavailability.

- IV administration is preferred in the critical care arena, because this allows for more rapid achievement of peak drug levels. Rapid absorption decreases the risk of dose stacking (administering multiple doses before the first dose has had time to act fully, leading to excessive dosing). When given intravenously, the drug distributes within <30 minutes. This allows for PRN doses to be given q30 minutes.

- Oral administration works fine, but absorption is slower. In order to avoid dose stacking, PRN doses must be spaced out more (at least 60 minutes between doses).

- Theoretically a risk of dose stacking could exist in patients with gastroparesis or related gastrointestinal pathologies.

- Intramuscular administration is another effective option.

1) Barbiturates have uniform efficacy, whereas benzodiazepines may fail to work.

- It's well established that a subset of patients will fail to respond to benzodiazepines, yet subsequently will be treated successfully with barbiturates. This occurs for the following reasons:

- (1) Benzodiazepines depend on the presence of endogenous presynaptic GABA molecules (so benzodiazepines won't work alone). Alternatively, phenobarbital is able to directly open GABA receptors (without any help from presynaptic GABA).

- (2) Benzodiazepines work only on GABA receptors, which is only part of the problem in alcohol withdrawal. In contrast, barbiturates also work on the glutamate system (down-regulating excitatory glutamate signaling by acting on the AMPA- and kainate-type glutamate receptors).(30876654)

- There don't appear to be patients who fail to respond to barbiturates which are dosed appropriately.

2) Benzodiazepines may cause paradoxical agitation and delirium. Barbiturates don't cause paradoxical reactions and seem to cause less delirium.

- Paradoxical agitation

- Benzodiazepines can occasionally cause paradoxical agitation. This is uncommon, but it is more frequently seen in patients with alcoholism. Paradoxical agitation can be enormously problematic when treating alcohol withdrawal, because this will amplify the agitation. If further benzodiazepines are given, this may lead rapidly to a vicious spiral of escalating benzodiazepine doses which precipitates intubation. 🌊

- Barbiturates don't appear to cause paradoxical agitation. This might reflect a more diffuse and balanced action of barbiturates on the brain, which doesn't leave some parts of the brain disinhibited.

- Delirium

- Benzodiazepines are notorious for causing delirium among critically ill patients. The fact that high-dose benzodiazepines can cause delirium in patients with alcohol has been shown (e.g. one study used flumazenil to combat benzodiazepine-induced delirium!).(24619543)

- Any psychoactive drug can cause delirium, so barbiturates may potentially do this as well. However, delirium seems to be less of an issue with barbiturates (this could also relate to the dosage of phenobarbital used, with judicious avoidance of toxic doses).

3) Phenobarbital has more predictable pharmacokinetics than benzodiazepines

- Once the pharmacokinetics of phenobarbital are understood, it's easy to estimate the phenobarbital level and efficacy within a specific patient. Alternatively, benzodiazepine pharmacokinetics are much more complex. This can make it difficult to determine whether a patient is experiencing excessive or deficient doses of benzodiazepine.

- For example: If a patient received 10 mg of lorazepam in divided doses over the last 12 hours, it's impossible to know how much lorazepam remains in their body. Alternatively, if a patient received 10 mg/kg phenobarbital over the last 12 hours, their phenobarbital level is extremely predictable (~15 ug/ml).

4) Phenobarbital has more predictable pharmacodynamics than do benzodiazepines

- The clinical response to benzodiazepines is variable:

- Most patients will respond well to relatively low doses (e.g. 50-100 mg diazepam).

- Some patients will require massive doses (e.g. 500 mg diazepam).

- Some patients will be entirely benzodiazepine-refractory.

- The clinical responsiveness to phenobarbital is more predictable (with a total dose range of roughly 5-25 mg/kg). This dose range is narrower than the effective dose range of benzodiazepines (perhaps 50-infinity mg of diazepam).

- Pharmacodynamic predictability can be helpful clinically to determine when alcohol withdrawal has been treated effectively (and thus when it's time to stop giving GABAergic medications). More on this below.

5) Phenobarbital has a greater therapeutic index than do benzodiazepines

- When given as monotherapy to a patient who isn't on benzodiazepine and has no other neurologic problems:

- The therapeutic dose of phenobarbital is ~5-25 mg/kg total body weight to achieve a serum level of ~10-40 ug/ml.

- The toxic dose of phenobarbital (the dose required to cause stupor/coma requiring intubation) is >40 mg/kg to achieve a serum level of >65 ug/ml.

- Thus, the dose of phenobarbital required to cause severe harm is really quite high (e.g. >2.5 grams). If phenobarbital is gradually up-titrated and capped at 30 mg/kg, it should be nearly impossible to cause stupor/coma from the phenobarbital itself.

- In contrast, benzodiazepine may have a smaller therapeutic index. The range of therapeutic doses is very broad (see #4), overlapping with the toxic dose range.

- Experience with procedural sedation teaches us that the dose of benzodiazepine required to sedate one person may equal the dose that would push another person into a coma.

6) The prolonged half-life of phenobarbital allows for precise dose-titration and gentle auto-tapering

- The long half-life of phenobarbital is one of its greatest strengths here. It allows for two therapeutic modalities which are largely impossible with benzodiazepines:

- (a) The total phenobarbital level can be gradually up-titrated over a period of 24-48 hours (with successive PRN doses). This allows for precise titration to achieve a patient-specific dose.

- (b) Once a therapeutic phenobarbital level is reached, this will very gradually auto-taper over several days (providing ongoing protection against rebound symptoms).

- This pharmacology stands in stark contrast with that of lorazepam (for example), which is difficult to maintain within a steady therapeutic level. Even if a patient can be rendered perfectly controlled with lorazepam, levels are likely to fall within the next several hours, leading to recrudescent symptoms. As such, patients may be left riding a lorazepam roller-coaster for days.

7) Phenobarbital may be superior for prevention of seizure

- Both benzodiazepines and barbiturates have anti-seizure activity. However, barbiturates may have some advantages over benzodiazepines:

- (a) Barbiturates in general have more potent anti-epileptic activity than do benzodiazepines (due to a broader range of neurotransmitter effects, as discussed above).

- (b) Some very weak data suggests that barbiturates may be superior in alcohol withdrawal seizure.(18975)

- (c) For patients who have had a seizure, dosing of phenobarbital is more straight-forward than dosing of a benzodiazepine. As discussed further below, phenobarbital can generally be raised to a therapeutic level for epilepsy (>15 ug/mL). 📖 In contrast, the appropriate dose of benzodiazepine to prevent recurrence of an alcohol-withdrawal seizure is largely guesswork.

8) Phenobarbital levels can be measured & levels have meaning

- Occasionally, we all encounter a patient where we get a bit lost. Perhaps the patient has been transferred between multiple hospitals or multiple units. It's unclear how much drug they received. They remain agitated – but are they under-medicated or over-medicated?

- If this occurs with phenobarbital monotherapy, the solution is simple – check a phenobarbital level.

- If this occurs with benzodiazepines, it may be impossible to sort out where you are.

9) Phenobarbital can be administered via all routes

- Phenobarbital can be given intravenously, orally, or intramuscularly. This facilitates seamless transition between different units which may administer phenobarbital via different routes (e.g. a patient might receive IV phenobarbital in the emergency department and later oral phenobarbital on the ward).

- This isn't unique (lorazepam or diazepam can also be given by multiple routes). However, it does represent an advantage over some benzodiazepines which are available only orally (e.g., oxazepam or chlordiazepoxide).

10) Phenobarbital has little sedating effect at moderate doses, allowing it to be given prophylactically

- A dose of 10 mg/kg phenobarbital will achieve a drug level of ~15 ug/ml. This drug level should have little to no sedating effect, allowing it to be given safely to a patient who is asymptomatic. This allows a meaningful dose of phenobarbital to be given in a preventative fashion, to prophylax against the development of alcohol withdrawal.📖

- A similar strategy is not possible with benzodiazepines, because in an asymptomatic patient benzodiazepines may have a sedating effect (figure above).

11) Phenobarbital has no real risk of propylene glycol intoxication

- Phenobarbital, lorazepam, and diazepam are all formulated in propylene glycol. Administration of large quantities of propylene glycol may lead to intoxication (with symptoms including delirium and metabolic acidosis).

- Lorazepam: This has the greatest risk of propylene glycol intoxication, because lorazepam wears off over hours and needs to be re-dosed frequently. In particular, giving lorazepam as a continuous infusion very often leads to propylene glycol accumulation.

- Diazepam: Propylene glycol is less common with diazepam, because diazepam's half-life is longer and less re-dosing is required.

- Phenobarbital: This carries no real risk of propylene glycol toxicity, because the total cumulative volume of drug required is relatively low (due to its half-life, phenobarbital accumulates and doesn't require prompt re-dosing).

12) Phenobarbital is widely available and potentially inexpensive

- Phenobarbital is part of the World Health Organization list of essential medications. It should be widely available at nearly any hospital.

- Intravenous phenobarbital is preferred for critically ill patients (due to faster onset and lower risk of dose-stacking). However, oral phenobarbital will work fine for the vast majority of patients. Oral phenobarbital is extremely inexpensive (e.g. a bottle containing 3.8 grams of phenobarbital costs under $20).

phenobarbital loading dose

- A dose of 10 mg/kg IV has been proven to be safe and to reduce the likelihood of ICU admission.(22999778)

- 10 mg/kg will achieve a serum phenobarbital level of ~15 ug/ml.

- This shouldn't cause significant somnolence on its own.

- Phenobarbital can cause synergistic sedation in combination with other drugs (especially benzodiazepines). Therefore, a loading dose could theoretically cause excessive sedation in a patient who has received a substantial dose of benzodiazepine.

- Beginning treatment of alcohol withdrawal with a loading dose of phenobarbital accelerates the achievement of an adequate serum drug level. You can achieve the same thing with numerous doses of 130-260 mg IV phenobarbital as needed, but it will take longer.

- Patients who were initially treated with a benzodiazepine may be transitioned over to therapy with phenobarbital monotherapy. However, if they have received a large dose of benzodiazepine, then the phenobarbital loading dose should be reduced or omitted.

phenobarbital titration

- Successive additional doses of phenobarbital may be given in a PRN fashion.

- The best validated strategy here is to use 130 mg IV q30 minutes to target a RASS score of 0-1.(29925291)

- Safety of the phenobarbital titration is generated by two factors:

- (1) Doses are provided in a small and incremental fashion – making it very unlikely that the patient would suddenly be pushed into a stuporous/comatose state.

- (2) The total cumulative dose of phenobarbital is limited to 20-30 mg/kg (which, by itself, shouldn't be a large enough dose to cause stupor/coma).

limit phenobarbital dose to 20-30 mg/kg

- The maximal dose of phenobarbital required to treat alcohol is unclear.

- Currently, 20-30 mg/kg phenobarbital seems like a reasonable stopping point, for the following reasons:

- A phenobarbital protocol at Massachusetts General Hospital was uniformly effective without requiring cumulative doses >20 mg/kg.(30876654) This study demonstrated that any residual symptoms unresponsive to such doses of phenobarbital could be safely treated by non-GABA-ergic medications (e.g. haloperidol).

- 30 mg/kg phenobarbital correlates roughly with ~40 ug/ml serum level, which is the upper limit of the therapeutic range for epilepsy. A limit of 30 mg/kg phenobarbital should keep levels within a range which is established to be generally safe.

- 20 mg/kg phenobarbital is a soft stop:

- The vast majority of patients with alcohol should be treatable with 20 mg/kg phenobarbital (plus other drug classes such as antipsychotics to treat any residual symptoms).

- Before exceeding 20 mg/kg, carefully re-evaluate the patient and ensure that symptoms are definitely due to alcohol withdrawal.

- For patients with a history of severe delirium tremens and refractory seizure, doses of 20-30 mg/kg might be reasonable to maximize the antiepileptic effects of phenobarbital.

- 30 mg/kg phenobarbital is a hard stop:

- Essentially all patients with alcohol withdrawal should be treatable with 30 mg/kg phenobarbital (plus other drug classes such as antipsychotics to treat any residual symptoms).

- Symptoms persisting beyond 30 mg/kg phenobarbital are unlikely due to alcohol withdrawal (they're increasingly likely to be due to non-alcohol-related delirium).

recognize the transition from alcohol withdrawal to Non-Alcohol-Related Delirium (NARD)

- Some patients with alcohol withdrawal may evolve into a non-alcohol-related delirium state (NARD, figure above).

- This is well-described among patients treated with benzodiazepine, who will often develop a benzodiazepine-induced delirium. One case series describes treatment of this condition with flumazenil! (24619543)

- NARD is less common among patients treated with phenobarbital, but may still occur (especially in patients with multiple medical problems).

- Timely recognition of NARD is critical, because ongoing treatment with GABAergic medications (benzodiazepines or barbiturates) will exacerbate this condition.

- Failure to diagnose NARD may lead to a vicious cycle of over-medication, which eventually precipitates stupor and coma.

- Clues to the development of NARD are the following:

- 🔎 Patient remains agitated or belligerent, but is showing no other signs of alcohol withdrawal (e.g. no tremor, hypertension, or tachycardia).

- 🔎 Symptoms persist longer than is typical for alcohol withdrawal treated with phenobarbital (e.g. >2-3 days). With ongoing time after admission, it's increasingly likely that the patient has nonspecific delirium and less likely that the patient has alcohol withdrawal.

- 🔎 Patient has already received a dose of phenobarbital which would be expected to be adequate for alcohol withdrawal (e.g. >20 mg/kg).

- NARD should be investigated and treated similarly to other agitated delirium states (more on this in the delirium chapter):

- The etiology should be evaluated (to exclude a serious underlying problem).

- Contributing factors should be eliminated if possible.

- Symptoms may be controlled (e.g. using haloperidol, dexmedetomidine, clonidine, or guanfacine).

1) wrong diagnosis / premature diagnostic closure

- Since phenobarbital is long-acting, any side-effects will also be long-acting.

- Prior to using phenobarbital, try to be fairly certain about the correct diagnosis.

- In cases of diagnostic uncertainty, titrated benzodiazepine might be a better option.

2) failure to keep track of the total phenobarbital dose

- The total cumulative phenobarbital dose must be monitored and limited to below 20-30 mg/kg.

- If there is uncertainty about the total phenobarbital dose, then checking a level may be useful.

3) use of phenobarbital to suppress a personality disorder

- Make sure that phenobarbital is being used to treat true symptoms of alcohol withdrawal.

- Never use phenobarbital to suppress a belligerent personality (without other signs/symptoms of alcohol withdrawal). Practitioners aren't doing this at a conscious level. However, patients who are aggressive will encourage a more heavy-handed approach to medication administration.

4) caution when combining phenobarbital and benzodiazepines

- Phenobarbital and benzodiazepines function synergistically. Therefore, a dose of phenobarbital which is safe by itself (say, 18 mg/kg) could cause respiratory suppression if paired with a large dose of benzodiazepines.

- Phenobarbital and benzodiazepines should never be titrated up simultaneously. Ideally once a decision has been made to use phenobarbital, no further benzodiazepines should be used.

- Once the patient has been titrated to a large cumulative dose of phenobarbital (e.g. >15 mg/kg), the risk of over-sedation with benzodiazepines increases.

5) be mindful of the contraindications to phenobarbital

- These are listed here: 📖.

situations where benzodiazepines are front-line include the following:

- (1) Diagnosis of alcohol withdrawal is unclear (see the section below on IV midazolam test dose).

- (2) Contraindications to phenobarbital (listed here: 📖).

- (3) Complex patient with numerous neurological problems (who might require close attention with ongoing dose-titration).

- (4) Advanced cirrhosis.

IV midazolam test dose

- Intravenous midazolam has a rapid onset and a short duration of action.

- Midazolam may be useful in situations where the diagnosis of alcohol withdrawal is unclear, to provide an empiric test dose of how the patient will respond to benzodiazepines.

- If a favorable response is achieved, then a longer-acting agent may be used.

- If a small dose of midazolam causes the patient to become sedated, the diagnosis of alcohol withdrawal is less likely (patients with alcohol withdrawal usually exhibit benzodiazepine tolerance).

IV diazepam is usually preferred over IV lorazepam

- Advantages of diazepam over lorazepam:

- Diazepam has faster onset (within 2-5 minutes), which prevents dose stacking. In contrast, lorazepam can take a while to work, which creates a risk of giving multiple doses before the initial doses have had a full effect (eventually leading to over-sedation which requires intubation).

- Diazepam has a longer duration of action (slow terminal half-life), which diminishes rebound symptoms.

- How to use IV diazepam:

- Diazepam is typically dosed with escalating doses as needed Q5-10 minutes (e.g. 10 mg, 10 mg, 20 mg, 20 mg, 20 mg, 40 mg, 40 mg, 40 mg).

- A subset of patients has benzodiazepine-resistant delirium tremens. If your patient isn't responding well to benzodiazepines, consider transitioning to phenobarbital.

IV lorazepam

- Lorazepam may be useful in the following situations:

- (1) Severe cirrhosis, which will impair metabolism of diazepam. If there is a risk of hepatic encephalopathy, prolonged sedation should be avoided. Titrated doses of lorazepam may be safest in this context. Other benzodiazepines which are relatively unaffected in cirrhosis are oxazepam and temazepam.

- (2) Neurocritically ill patients – In complex patients with fluctuating levels of consciousness, a shorter-acting benzodiazepine may provide more flexibility in dose-titration.(32794143)

- High doses of IV lorazepam will eventually cause propylene glycol toxicity. For patients who requiring large doses of lorazepam, consider supplementation with phenobarbital or switching to diazepam.

advantages of valproic acid in alcohol withdrawal:

- Antiseizure activity.

- Mood stabilizing properties may be helpful for patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders.

- Valproate has fewer drug-drug interactions than phenobarbital.

- Valproate may be less sedating than benzodiazepines or barbiturates.(32794143)

- Supported by some evidence in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal (albeit much less than benzodiazepines or barbiturates).(11916372, 21339186, 34674404, 11584152)

additional information on valproic acid (including contraindications, dosing): 💉

role of valproic acid in alcohol withdrawal

- Valproic acid isn't a front-line therapy, but may be considered for selected patients.

- Valproic acid can be used in combination with benzodiazepines (valproate has a benzodiazepine-sparing effect).(32794143)

- Valproic acid may be especially useful in:

- Patients with contraindications to phenobarbital.

- Alcohol withdrawal seizures, or pre-existing epilepsy.

- Comorbid psychiatric disorders.

- Persistent agitation that doesn't respond to other treatments.

these agents (e.g., haloperidol, clonidine, dexmedetomidine) should generally be avoided during initial treatment:

- They don't treat the underlying problem (inadequate GABA signaling and excessive glutamate activity).

- They lack anti-seizure properties.

- They may mask the symptoms of alcohol withdrawal, without addressing the real problem.

- They should never be used as the sole or primary therapy for alcohol withdrawal.

potential uses of dexmedetomidine

- Dexmedetomidine is an intravenous alpha-2 agonist that may be used to provide titratable sedation (without respiratory suppression). It is a niche agent, with some potential uses as follows:

- (1) Achieve behavioral control while you're working on gradual up-titration of phenobarbital or performing other tests (e.g. lumbar puncture). In complex patients, this can be helpful for buying time that allows you to sort out exactly what is going on.

- (2) Non-alcohol related delirium (more on this below).

antipsychotics and alpha-2 agonists may be useful for treating non-alcohol related delirium (NARD)

- Some patients will develop a nonspecific, mixed delirium state following treatment for alcohol withdrawal (NARD, see figure above). This may be treated similarly to other patients in the ICU with delirium. Antipsychotics (e.g., small doses of PRN IV haloperidol) and alpha-agonists (e.g. dexmedetomidine) may be helpful.

- For example, imagine a patient who has already received a substantial amount of phenobarbital (e.g. >15 mg/kg) and is getting increasingly agitated overnight. Dexmedetomidine is a great drug for nocturnal delirium, so this can help get the patient some sleep overnight. Stop the dexmedetomidine the next morning and re-assess whether more phenobarbital is required. A patient who is suffering from nonspecific ICU delirium (rather than alcohol withdrawal) may be perfectly fine the next morning when the dexmedetomidine is discontinued.

further discussion of these agents:

- Antipsychotics:

- Alpha-2 agonists:

ketamine has many desirable properties

- Doesn't suppress respiration.

- Effective analgesic.

- Effective anti-epileptic.

- Immediately available in most critical care settings.

dissociative ketamine

- Rarely, a dissociative dose of ketamine (e.g. 1.5-2 mg/kg) may be useful for a patient with alcohol withdrawal who is dangerously agitated. In practice, this should only rarely be encountered.

- Dissociative ketamine will achieve behavioral control for ~30 minutes. This is enough time to order phenobarbital and start it running in (e.g., 5-10 mg/kg depending on the context). As the patient is waking up from the ketamine, phenobarbital may be used to prevent re-emergence. Benzodiazepines may also be used in a similar fashion.

pain-dose ketamine

- Untreated pain can be a problem for patients with alcohol withdrawal. Pain can be a driver of agitation, which may potentially lead to excessive use of sedatives.

- A pain-dose ketamine infusion is a nice option for the patient with alcohol withdrawal and active pain. The management here is similar to the use of low-dose ketamine infusion for pain in other contexts. 📖

More on ketamine: 💉

electrolytic repletion

- Patients are often deficient in multiple electrolytes (especially potassium, magnesium, and phosphate). Specifically:

- (1) Severe alcoholism often causes a severe total-body magnesium deficit, which may require numerous doses of intravenous magnesium to correct (or a magnesium infusion).

- (2) Patients with alcoholism are at increased risk for refeeding syndrome – which may require substantial quantities of phosphate repletion.

glucose monitoring

- Follow glucose levels intermittently in patients who are NPO. Patients with alcoholism and cirrhosis may have impaired liver glycogen reserves, which puts them at risk for hypoglycemia.

vitamin B1 (IV thiamine)

- Alcoholic patients are often thiamine deficient. These patients may develop Wernicke's encephalopathy, which can mimic alcohol withdrawal. It's often impossible to clinically exclude Wernicke's encephalopathy (because patients with alcohol withdrawal may not cooperate with a full neurologic examination).

- When in doubt, the safest thing is to administer high-dose thiamine (500 mg IV q8hr). This will treat Wernicke's encephalopathy if it is present (and it extremely safe regardless).

refeeding syndrome

- Severe alcoholics with poor nutrition may be at risk for refeeding syndrome.

- Further discussion of preventing and treating refeeding syndrome: 📖

general

- ⚠️ Alcohol withdrawal seizures are usually self-limiting, but they tend to recur in most patients if untreated. Even if the patient has recovered fully, immediate treatment is needed to prevent recurrence (which can lead to status epilepticus in 3% of patients).(32256131)

clinical presentation

- Seizures usually occur 12-24 hours after the last drink, but the risk of seizures extends for ~48 hours.(32256131) They can be a relatively early manifestation of alcohol withdrawal, occuring in a patient who is otherwise doing OK.

- Seizures are usually generalized tonic-clonic seizures that are brief and self-limiting. However, seizures have a tendency to recur in clusters (e.g., 2-6 seizures).

evaluation

- Consider alternative causes of seizure, especially if the patient doesn't respond well to therapy.

- Patients with alcoholism have high rates of trauma and may have intracranial hemorrhage.

treatment

- Traditional antiepileptic drugs may not work (especially phenytoin, which lacks activity against this seizure type).

- Phenobarbital is often an excellent choice (given the ability of phenobarbital to treat alcohol withdrawal and treat seizure).

- A usual loading dose of phenobarbital for the treatment of seizure is ~15-20 mg/kg. If the patient's mental status is reasonably normal, then phenobarbital may be given in divided doses with a goal of titrating up to a total dose of ~15-20 mg/kg.

- Benzodiazepines are an alternative treatment, if phenobarbital is contraindicated. In animal models, benzodiazepines demonstrate low antiseizure epilepsy, likely due to benzodiazepine tolerance.(32794143)

- Valproic acid may be useful (with activity against seizures and alcohol withdrawal). 📖

vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) may be considered for seizure

- Pyridoxine deficiency is well known to promote seizures in various clinical scenarios (e.g. isoniazid use and pregnancy).

- Alcoholism is one cause of pyridoxine deficiency. Some emerging literature suggests that occasional patients with alcoholism may develop seizures due to pyridoxine deficiency.(25343127, 26157671)

- Testing for pyridoxine deficiency is possible (e.g. measurement of homocysteine levels). However, it may be easier to simply empirically administer pyridoxine to alcoholic patients with who have seizures. Oral or intravenous pyridoxine is widely available.(28789699)

clinical presentation

- As the name may suggest, patients present with subacute encephalopathy in the context of chronic alcoholism. Encephalopathy may include features such as lethargy, confusion, delirium, obtundation, agitation, and/or disorientation.

- Transient focal neurologic defects often occur (including hemiparesis, aphasia, neglect, cortical blindness, and hemianopsia).(30955427)

- Patients often have focal motor seizures (~40% of patients) or complex partial seizures. Complex partial status epilepticus may occur, which may account for mental status alterations.(30955427) Focal seizures can evolve into generalized tonic/clonic seizures.

EEG findings

- Baseline EEG findings include focal slowing, spiking, and LPDs (lateralized periodic discharges).

- These findings help distinguish SESA syndrome from chronic alcoholism alone, since the latter generally doesn't lead to striking EEG changes.(30955427)

- LPDs usually disappear during focal seizures or complex partial status epilepticus. Following seizure resolution, LPDs may reappear (reflective of a true ictal-interictal continuum).(30955427)

neuroimaging

- MRI often shows cortical-subcortical areas of hyperintensity on T2/FLAIR sequences, which may have restricted diffusion. These abnormalities correlate anatomically with LPDs (lateralized periodic discharges). Advanced imaging shows increased perfusion of these areas, reflective of an ongoing focal epileptic event.(30955427)

- Follow-up MRI often shows resolution of these abnormalities, but there may be progression to focal atrophy.

- Thalamic abnormalities may also be seen in patients with nonconvulsive status epilepticus.(30955427)

treatment

- Patients respond well to anti-seizure medications, although confusion may be prolonged.

- Various anti-seizure medications have been used (including phenytoin, valproate, levetiracetam, and lacosamide).(30955427)

- Unlike transient alcohol withdrawal seizures, SESA syndrome requires ongoing therapy with with antiseizure medication, to prevent recurrence. Alcohol cessation is also essential.

going further

- Open-access review article by JL Fernandez-Torrez and PW Kaplan 📄

- Tweetorial by Casey Albin 10/17/21 🌊

- Tweetorial by Jimmy Suh 12/10/21 🌊

criteria for prophylactic phenobarbital:

- (1) Must have a definite history of severe, steady alcohol intake up until the time of admission.

- Verify with the patient/family that there is ongoing alcohol use.

- (2) Felt to be at significant risk from alcohol withdrawal, for example:

- (a) History of alcohol withdrawal (especially prior seizures or delirium tremens).

- (b) Co-existent medical problem which could be exacerbated by withdrawal (e.g. unstable angina).

- (3) Normal mental status, with no active neurologic problems.

- (4) No risk factors for over-sedation due to phenobarbital:

- Not on benzodiazepines, high-dose opioids, or multiple drugs that may cause respiratory suppression

- No history of hepatic encephalopathy.

- (5) No contraindication to phenobarbital (these are listed here: 📖).

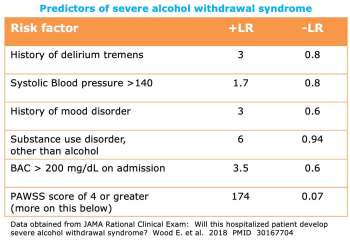

evidence-based prediction of the risk of alcohol withdrawal

- In situations where the risk of alcohol is unclear, the above factors may be considered.

- The best predictor of severe alcohol withdrawal seems to be the PAWSS score (calculator here: 🧮).

procedure for prophylactic phenobarbital

- Try to provide the patient with a total of 10-15 mg/kg phenobarbital (cumulative dose).

- 10 mg/kg is generally a reasonable target.

- 15 mg/kg in divided doses might be preferable for a patient at very high risk of complicated withdrawal (e.g., prior history of seizures).

- Phenobarbital is often provided in repeated doses ~5-7.5 mg/kg. Intravenous or oral phenobarbital may be used.

Alcohol may rarely be used to prevent withdrawal. This could be sensible in the following situation:

- Patient has decisional capacity and clearly intends to continue drinking.

- Patient isn't NPO.

- Alcohol is available (either it's on hospital's formulary, or the patient's family can provide some).

A large amount of alcohol may not be required to prevent withdrawal; often 1-2 drinks per night will be sufficient. If this isn't an option, phenobarbital may also be used to prevent withdrawal (as described above).

Follow us on iTunes

The Podcast Episode

Want to Download the Episode?

Right Click Here and Choose Save-As

To keep this page small and fast, questions & discussion about this post can be found on another page here.

- Failure to take an accurate history of alcohol use.

- Failure to keep track of the cumulative phenobarbital dose (and stop after reaching a dose >20-30 mg/kg).

- Concluding that phenobarbital isn't working (and therefore the patient must be intubated) prior to using an adequate phenobarbital dose.

- More pitfalls: Pitfalls of phenobarbital (above)

Guide to emoji hyperlinks

= Link to online calculator.

= Link to Medscape monograph about a drug.

= Link to IBCC section about a drug.

= Link to IBCC section covering that topic.

= Link to FOAMed site with related information.

= Link to supplemental media.

References

- 18975 Smith RF. Relative effectiveness of primidone (Mysoline) and diphenylhydantoin (Dilantin) in the management of sedative withdrawal seizures. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1976;273:378-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1976.tb52903.x [PubMed]

- 01587059 Wilkes L, Danziger LH, Rodvold KA. Phenobarbital pharmacokinetics in obesity. A case report. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1992 Jun;22(6):481-4. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199222060-00006 [PubMed]

- 01986421 Ives TJ, Mooney AJ 3rd, Gwyther RE. Pharmacokinetic dosing of phenobarbital in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome. South Med J. 1991 Jan;84(1):18-21. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199101000-00006 [PubMed]

- 03973064 Browne TR, Evans JE, Szabo GK, Evans BA, Greenblatt DJ. Studies with stable isotopes II: Phenobarbital pharmacokinetics during monotherapy. J Clin Pharmacol. 1985 Jan-Feb;25(1):51-8. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1985.tb02800.x [PubMed]

- 07068937 Nelson E, Powell JR, Conrad K, Likes K, Byers J, Baker S, Perrier D. Phenobarbital pharmacokinetics and bioavailability in adults. J Clin Pharmacol. 1982 Feb-Mar;22(2-3):141-8. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1982.tb02662.x [PubMed]

- 20682131 Tangmose K, Nielsen MK, Allerup P, Ulrichsen J. Linear correlation between phenobarbital dose and concentration in alcohol withdrawal patients. Dan Med Bull. 2010 Aug;57(8):A4141 [PubMed]

- 22999778 Rosenson J, Clements C, Simon B, Vieaux J, Graffman S, Vahidnia F, Cisse B, Lam J, Alter H. Phenobarbital for acute alcohol withdrawal: a prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Emerg Med. 2013 Mar;44(3):592-598.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.07.056 [PubMed]

- 24619543 Moore PW, Donovan JW, Burkhart KK, Waskin JA, Hieger MA, Adkins AR, Wert Y, Haggerty DA, Rasimas JJ. Safety and efficacy of flumazenil for reversal of iatrogenic benzodiazepine-associated delirium toxicity during treatment of alcohol withdrawal, a retrospective review at one center. J Med Toxicol. 2014 Jun;10(2):126-32. doi: 10.1007/s13181-014-0391-6 [PubMed]

- 25343127 Tong Y. Seizures caused by pyridoxine (vitamin B6) deficiency in adults: A case report and literature review. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2014 May;3(2):52-6. doi: 10.5582/irdr.2014.01005 [PubMed]

- 26157671 Lee DG, Lee Y, Shin H, Kang K, Park JM, Kim BK, Kwon O, Lee JJ. Seizures Related to Vitamin B6 Deficiency in Adults. J Epilepsy Res. 2015 Jun 30;5(1):23-4. doi: 10.14581/jer.15006 [PubMed]

- 28789699 Dilrukshi MDSA, Ratnayake CAP, Gnanathasan CA. Oral pyridoxine can substitute for intravenous pyridoxine in managing patients with severe poisoning with isoniazid and rifampicin fixed dose combination tablets: a case report. BMC Res Notes. 2017 Aug 8;10(1):370. doi: 10.1186/s13104-017-2678-6 [PubMed]

- 29925291 Oks M, Cleven KL, Healy L, Wei M, Narasimhan M, Mayo PH, Kohn N, Koenig S. The Safety and Utility of Phenobarbital Use for the Treatment of Severe Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome in the Medical Intensive Care Unit. J Intensive Care Med. 2020 Sep;35(9):844-850. doi: 10.1177/0885066618783947 [PubMed]

- 30876654 Nisavic M, Nejad SH, Isenberg BM, Bajwa EK, Currier P, Wallace PM, Velmahos G, Wilens T. Use of Phenobarbital in Alcohol Withdrawal Management – A Retrospective Comparison Study of Phenobarbital and Benzodiazepines for Acute Alcohol Withdrawal Management in General Medical Patients. Psychosomatics. 2019 Sep-Oct;60(5):458-467. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2019.02.002 [PubMed]

- 30955427 Fernández-Torre JL, Kaplan PW. Subacute Encephalopathy With Seizures in Alcoholics Syndrome: A Subtype of Nonconvulsive Status Epilepticus. Epilepsy Curr. 2019 Mar-Apr;19(2):77-82. doi: 10.1177/1535759719835676 [PubMed]

- 32256131 Wolf C, Curry A, Nacht J, Simpson SA. Management of Alcohol Withdrawal in the Emergency Department: Current Perspectives. Open Access Emerg Med. 2020 Mar 19;12:53-65. doi: 10.2147/OAEM.S235288 [PubMed]

- 32794143 Farrokh S, Roels C, Owusu KA, Nelson SE, Cook AM. Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome in Neurocritical Care Unit: Assessment and Treatment Challenges. Neurocrit Care. 2021 Apr;34(2):593-607. doi: 10.1007/s12028-020-01061-8 [PubMed]