Here are the answers to todays discussion questions on ABG & VBG.

A woman with history of heart failure, COPD, and recent international plane travel presents with dyspnea to the ED. ABG shows 7.52/29/65/23. What does this test reveal about her diagnosis? (2/6)

— 𝙟𝙤𝙨𝙝 𝙛𝙖𝙧𝙠𝙖𝙨 (he/him) 💊 (@PulmCrit) September 4, 2019

(1) Answer = 4. The ABG provides no diagnostic information. An extremely common (incorrect) belief about ABGs is that they provide diagnostic information. Available evidence indicates that this is generally not the case. The only situations in which ABGs provide specific diagnostic information are as follows:

- ABG with crazy low pCO2 and normal A-a gradient supports a diagnosis of hyperventilation/anxiety.

- ABG with a normal A-a gradient argues strongly against asthma, may be used to support a competing diagnosis of vocal cord dysfunction.

ABGs provides no useful information to sort out most common respiratory disorders (CHF, COPD, PE, etc.). More on this here: approach to undifferentiated resp failure.

A man with COPD presents with initial ABG 7.25/70/55/30. His mentation is fine, but he has substantial work of breathing with RR 35. After two hours of BiPAP he is feeling & looking better with RR 27/min. Repeat ABG shows 7.23/74/130/30. What is best management? (3/6)

— josh farkas 💊 (@PulmCrit) September 4, 2019

(2) Best answer = 3. The patient is clearly improving clinically, so intubation isn't indicated (that is a clinical decision). His pCO2 is increased trivially but that is close to within random variation of pCO2 and probably not a clinically significant increase. The fact that his pCO2 is roughly stable with a marked decrease in his respiratory rate (from 35 to 27) suggests that his breathing is more effective (less dead space) – suggestive of clinical improvement.

He is probably receiving a bit more oxygen than he needs. Excessive oxygenation may impair VQ matching slightly, thereby increasing the pCO2 somewhat. So down-titrating his oxygen to target a saturation of 88-92% would be sensible (more on this in a RebelEM post here). However, realistically, this probably doesn't really matter. He is improving clinically, if you just continue to support him and monitor him clinically he will probably continue to recover. Less is more here. Follow him clinically (resp rate, mental status, tidal volume & minute ventilation on BiPAP). One small pearl here, by the way, is that monitoring the BiPAP parameters and trending them can be a really useful indicator of which direction things are going (if there is a good mask seal, the BiPAP provides a wealth of information about ventilation).

A man presents with history of productive cough, fever, and dyspnea. His PMH is notable for severe OSA/OHS and chronic use of high-dose hydromorphone for back pain. Currently he is sleepy but easily arousible. ABG shows 7.2/105/65/40. What does this test mean? (4/6)

— josh farkas 💊 (@PulmCrit) September 4, 2019

(3) Choice 4: ABG provides no diagnostic information. The key message here is similar to question #1 above: ABG fails as a diagnostic test. But there's another pearl contained here as well. A patient with chronic hypercarbic respiratory failure will develop worsening hypercarbic respiratory failure due to any respiratory insult. Essentially, anything may push this patient into developing worsening hypercarbia (e.g. pulmonary embolism, COPD, pneumonia, heart failure). The increase in pCO2 is a bad thing and reveals that he is ill, but it provides zero diagnostic information.

A mistake here would be to conclude that PNA is typically associated with lower pCO2 values, and therefore, the patient cannot have a pneumonia. Based on the case presented in the question stem, this patient very likely does have pneumonia. It's likely that he has pneumonia causing an exacerbation of his respiratory muscle failure due to OSA/OHS… and of course the hydromorphone isn't helping either.

A COPD patient is about to leave ICU when she gets a bit sleepy. ABG shows 7.04/120/53/31 with a good pulse oximetry waveform showing saturation of 98% on 4 liters. Which of the following is most accurate? (5/6)

— josh farkas 💊 (@PulmCrit) September 4, 2019

(4) Choice B: This patient was ordered to get an “ABG” but actually got a venous blood gas. You can tell this is a venous draw because the oxygen level is mismatched compared to her oxygen saturation (a pO2 of 53 mm would usually correlate to a saturation around 88-90%, not 99%. A good rule of thumb here is that pO2 of 60mm usually correlates with a saturation of 90%). This is extremely common – some studies suggest that around 15% of “ABG” values are in fact venous blood gas draws which occurred erroneously.

But this doesn't matter! The VBG value is really just as good as an ABG value here. The test reveals that she is extremely hypercarbic, which explains her somnolence. This is diagnostic and actionable data, which is just as good as an ABG in this situation.

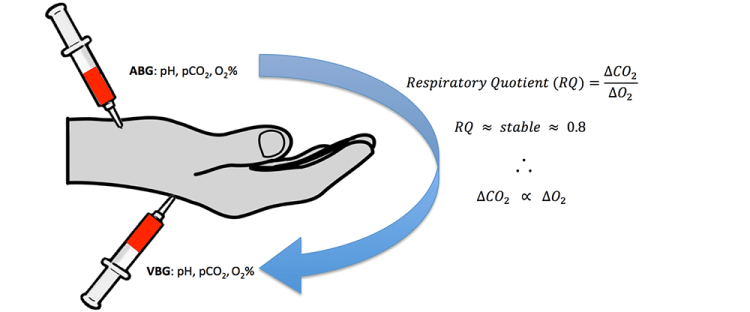

Differences between VBG and ABG values are roughly correlated to the difference in oxygen saturation between the VBG and ABG. With her VBG oxygen saturation of around 88%, her VBG will be nearly exactly the same as her ABG value. So there is no need to repeat this – the VBG provides accurate information. More on the rabbit hole of ABG/VBG correlation and conversion here.

There is no need to intubate if she is only slightly somnolent and protecting her airway. BiPAP could be trialed for this patient and she will probably improve. As mentioned earlier, the decision to intubate is a clinical one primarily (not dictated by any specific numbers in the ABG or VBG). She should also be investigated for any other causes of respiratory failure (e.g. opioids, pneumothorax, pneumonia, aspiration) – an investigation which may be undertaken with lung ultrasonography and chest x-ray.

That's all for now, eventually we will have an IBCC chapter on this, but for now here are some more links on ABG/VBG, cheers, josh.