One of the most notable controversies in COVID is when steroid might be beneficial. Since steroid is widely available and inexpensive, this issue has escaped the attention of pharmaceutical companies. Consequently, evidence surrounding this is extremely sparse.

Available evidence consists largely of retrospective studies which relate steroid administration to outcome. Such studies are inherently flawed, because steroid is selectively administered to the sickest patients. Thus, if steroid had no effect at all, one might expect a correlation between steroid and worse outcomes. In practice, these studies reveal mixed outcomes. The fact that steroid use has correlated with improved outcomes in some studies runs opposite to the expected correlation, suggesting that steroid might be beneficial.

RCTs would obviously be the highest level of evidence. Fortunately, some RCTs are designed to evaluate the effect of steroids in COVID-19. While we await these studies, we are left to scrutinize other data.

In the hierarchy of trial designs, somewhere between retrospective correlational studies and RCTs lie before/after studies. These compare outcomes of two groups of patients before and after a change in the general treatment protocol. These are fundamentally correlative studies, so they still suffer from potential confounding factors (e.g., due to unrelated improvements in patient care over time). However, before/after trials may be less severely flawed than purely retrospective trials, because they avoid selective administration of treatment to individual patients.

Fadel R et al. Early short course corticosteroids in hospitalized patients with COVID-19

This is a multi-center pre/post study evaluating the effect of a protocol involving early steroid administration within a health system in Michigan (including five hospitals).1

Consecutive patients were retrospectively included if they met the following criteria:

- Confirmed COVID-19 infection

- Bilateral pulmonary infiltrates

- Hypoxemic respiratory failure (requiring either low-flow nasal cannula, high-flow nasal cannula, or mechanical ventilation)

- Not being transferred from an out-of-system hospital

- Not dying or being discharged from the hospital within 24 hours

Institutional protocols were changed on March 20th to include early administration of corticosteroid (0.5-1 mg/kg per day in two divided doses, for a duration of three days among ward patients and 3-7 days among ICU patients). This was based on poor outcomes using the initial protocol, as well as the emergence of new data that steroid might be beneficial.2 Patients admitted between 3/12-3/19 (pre-steroid) were compared to patients admitted the following week 3/20-3/27 (post-steroid). Throughout this two-week period, most other treatment elements seem to have remained constant. One exception is that lopinavir/ritonavir with ribavirin was removed from the institutional protocol on 3/17.

213 patients were included, as shown below. Groups were generally fairly well matched, with the exception of an increase in body mass index and small shift in ethnicity (table below). The median duration of illness prior to admission was 5 days.

Laboratory values between both patient groups were very similar:

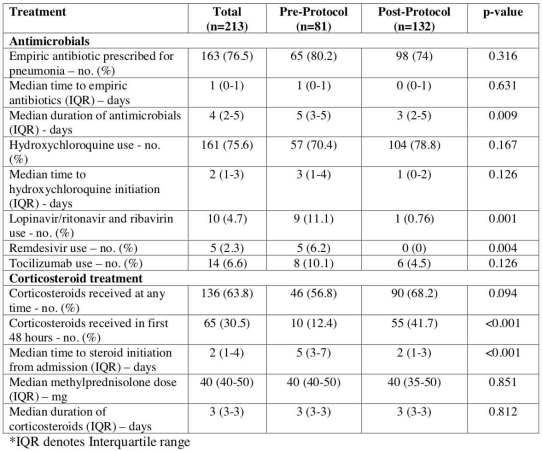

Treatments received are shown below. Over time, there was a reduction in the use of lopinavir/ritonavir/ribavirin, remdesivir, and tocilizumab (although few patients received these treatments). Patients in both groups had a high rate of steroid usage. However, originally steroid was initiated relatively late in the patient stay. After the change in protocol, steroid was more often initiated early:

The primary endpoint was a composite of clinically significant deterioration (ICU admission if the patient wasn’t already in ICU, intubation, or mortality). The primary endpoint and numerous secondary endpoints were positive:

Since this isn’t an RCT, there is a possibility that these results could result from confounding variables. A multivariable logistic regression equation was constructed including numerous prognostic factors. Even when accounting for other prognostic factors, the use of the corticosteroid protocol correlated with a reduction in composite clinical deterioration (the primary endpoint):

limitations

As a pre/post trial, this study cannot prove causality. The primary weakness is that subtle changes in the management of COVID-19 patients could have occurred during this two-week time period, causing gradual improvements over time. For example, it’s possible that greater efforts to avoid early intubation could have contributed to a reduction in intubation rates and downstream iatrogenic harms. However, the entire study was conducted over only two weeks, making it less likely that drift in usual care processes was substantial.

After implementation of the early-steroid protocol, only 42% of patients actually received steroid within 48 hours of admission. This could reflect delayed adoption of the new protocol, or it could reflect that providers remained selective about who to treat with steroid. Thus, this report cannot be interpreted as evidence that every single patient should be treated with steroid.

In fact, the amount of steroid exposure was similar in both patient groups. Initially, steroid was initiated later in the disease course, possibly as salvage therapy. After the change in protocol, steroid was initiated earlier, as a pre-emptive strategy to prevent deterioration. Another cause of delayed steroid initiation among the first patient group is that some patients remained in the hospital following the change in protocol, thus causing delayed cross-over into a steroid strategy. Thus, an early steroid strategy effectively shifted the timing of steroid use to a point where it might cause more benefit. One potential pitfall of this design is that there was no true comparison to a non-steroid group (the study effectively compares early-steroid vs. late-steroid, not early-steroid vs. no-steroid).

Fitting this study into the larger clinical context

The use of steroid in COVID-19 remains highly controversial. For example, the Surviving Sepsis Campaign and Canadian guidelines both recommend steroid for intubated COVID patients with ARDS, whereas other guidelines contradict these guidelines.3,4 Accumulating evidence indicates that a hyperinflammatory response contributes to lung injury, coincident with the emergence of acquired immunity (after ~5-10 days of clinical symptoms). This supports the use of anti-inflammatory medication (whether this may optimally be corticosteroid, anakinra, tocilizumab, or perhaps JAK inhibitors). For the moment, corticosteroids appear to be supported by the greatest volume of evidence (especially in terms of a well-established side-effect profile).

The use of steroids is more widely accepted among intubated patients than among non-intubated patients. However, the act of intubation changes nothing about the immunobiology of COVID-19. Thus, if corticosteroid is advisable in intubated COVID patients with ARDS, it’s likely that it could also benefit severely ill patients at risk of requiring intubation (particularly if we aren't pursuing an early-intubation strategy). The current study supports this line of reasoning – that steroid might be best employed pre-emptively with a view toward avoiding deterioration and intubation:

- The use of steroid in COVID-19 remains controversial. Guidelines disagree about whether to give steroid to intubated patients with ARDS. Current trends involve earlier use of steroid with a goal of avoiding intubation, but little high-quality data exists.

- Fadel et al. is a retrospective pre/post trial evaluating the use of a steroid in patients with COVID-19 hospitalized at a network of five hospitals in Michigan. Adoption of a protocol involving early administration of 0.5-1 mg/kg methylprednisolone daily correlated with improvements in numerous outcomes (e.g., reductions in clinical deterioration, intubation, and mortality).

- As a pre/post trial, this study cannot prove causality. Temporal improvements in care processes likely cause some degree of confounding.

- RCTs will be needed to clarify the role of steroid in COVID-19. For now, this study weakly supports a strategy of starting moderate dose steroid for hospitalized patients who are roughly a week into their illness.

related

- Timed and titrated use of steroid in COVID-19 (PulmCrit)

- COVID-19 clinical/therapeutic staging (Salim Rezaie, RebelEM)

- IBCC chapter: Steroid for COVID-19 with substantial hypoxemia

- Steroid for ARDS? DEXA-ARDS (PulmCrit)

Image credit: Photo by Hans-Peter Gauster on Unsplash

references

- 1.Fadel R, Morrison A, Vahia A, et al. Early Short Course Corticosteroids in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19. Published online May 5, 2020. doi:10.1101/2020.05.04.20074609

- 2.Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, et al. Risk Factors Associated With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Death in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. Published online March 13, 2020. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994

- 3.Alhazzani W, Møller MH, Arabi YM, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Intensive Care Med. Published online March 28, 2020:854-887. doi:10.1007/s00134-020-06022-5

- 4.Ye Z, Rochwerg B, Wang Y, et al. Treatment of patients with nonsevere and severe coronavirus disease 2019: an evidence-based guideline. CMAJ. Published online April 29, 2020:cmaj.200648. doi:10.1503/cmaj.200648

- Pulmcrit wee: The cutoff razor - April 15, 2024

- PulmCrit Blogitorial – Use of ECGs for management of (sub)massive PE - March 24, 2024

- PulmCrit Wee: Propofol induced eyelid opening apraxia – the struggle is real - March 20, 2024

Great article. This definitely fits with what I am seeing anecdotally. Especially with regards to those “at risk for intubation” that you mention above. Again, I realize this is anecdotal, but I have had several younger (40s) patients presenting hypoxic and unable to get their sats up above 80s despite proning and a 100%NRB (our high-flows are very limited). I gave solumedrol 125 and an hour later their improvement was significant with them breathing much more comfortably with sats in low to mid 90s. Not enough obviously to draw a hard conclusion, but combined with evidence like you cite in… Read more »

Important discussion – thank you. There is another mechanistic rationale in support of the (temporary) use of corticosteroids in ventilated COVID19 patients: Mechanical ventilation causes alveolar epithelial cell, via secretion of the mediator midkine, to increase expression of ACE2 – the virus receptor on cells! T Thus, we have a vicious cycle for viral spread when patients are put on mechanical ventilation: The mechanical stress inflicted by PEEP ventilation to the alveolar cells specifically increases the susceptibility of alveolar cells to SARS-Cov2 infection! In fact, post-mortem lung tissues from patients in the GTEx database that were on mechanical ventilation showed… Read more »

https://journals.lww.com/ccejournal/fulltext/2020/06000/the_combination_of_tocilizumab_and.23.aspx

Our report support the benefits of steroids.