CONTENTS

- Rapid Reference 🚀

- Pathophysiology

- Epidemiology

- Clinical presentation

- Diagnosis & differential diagnosis

- Evaluation of the underlying cause

- Treatment overview

- Podcast

- Questions & discussion

- Pitfalls

if hypovolemic, provide volume resuscitation:

- Bicarb <22 mM

use isotonic bicarbonate.

- Bicarb >22 mM

use lactated Ringers or plasmalyte.

- Target achieving euvolemia with a bicarbonate of ~24-28 mEq/L.

treat bradycardia 📖

- IV calcium is the front line therapy:

- Start with 1 gram of calcium chloride, or 3 grams of calcium gluconate.

- May repeat if necessary.

- Epinephrine or isoproterenol infusion at ~2-10 mcg/min, for patients with ongoing bradycardia and hypotension.

- ⚠️ Beware of normotensive malperfusion. Some patients compensate for bradycardia by developing intense vasoconstriction. For patients with bradycardia, normotension, and malperfusion (e.g., poor urine output and cool extremities), try increasing the heart rate with dobutamine or isoproterenol.

treatment of hyperkalemia 📖

- Dextrose/insulin:

- 5 units insulin as an intravenous bolus.

- If glucose <250 mg/dL (<14 mM), give ~two ampules of D50W (100 ml total) –or– ~500 ml of D10W infused over four hours.

- Beta-2 agonist: (omit if on epinephrine/isoproterenol infusion)

- Albuterol: 10-20 mg nebulized (e.g., 4-8 standard nebs back-to-back, or a continuous neb).

- Terbutaline 7 mcg/kg s.q. (or ~0.5 mg).

- Kaliuresis for patients who can produce urine:

- Relatively normal renal function: IV loop diuretic alone may be sufficient (e.g., 60-160 mg IV furosemide).

- Moderate/severe renal dysfunction with possible need for emergent dialysis: Attempt to avoid dialysis using the nephron bomb:

Loop diuretic (e.g., 160-250 mg IV furosemide or 4-5 mg IV bumetanide).

Thiazide (500-1,000 mg IV chlorothiazide, or 5-10 mg metolazone).

+/- Acetazolamide (250-1,000 mg IV/PO).

+/- Fludrocortisone 0.2 mg PO (esp. patients on ACEi/ARB, tacrolimus).

- Replace urine losses with crystalloid to avoid hypovolemia.

- Sodium zirconium cyclosilicate 💉 10 mg PO q8hr may be considered.

- Dialysis if refractory to diuresis, or chronic dialysis dependence.

BRASH syndrome is defined as a combination of the following:

- Bradycardia

- Renal failure (either acute or acute-on-chronic)

- AV node blocker

- Usually due to a beta blocker, verapamil, or diltiazem.

- A recent case report suggested that ranolazine may act similarly)(31975993)

- Shock

- Hyperkalemia

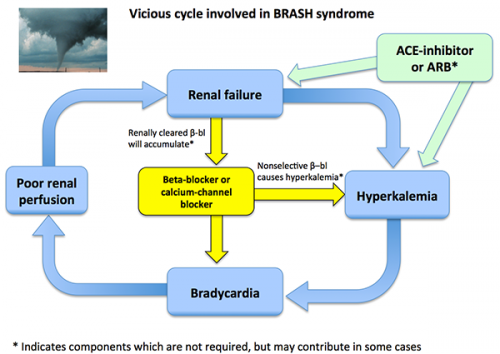

the core physiology of BRASH syndrome: synergistic bradycardia

- Hyperkalemia is well known to cause bradycardia. However, this effect is generally restricted to relatively severe hyperkalemia.

- AV nodal blockers obviously can cause bradycardia, but this effect generally isn't marked at therapeutic doses.

- The core physiology of BRASH syndrome is that hyperkalemia plus AV nodal blockers together may synergize to cause bradycardia. Due to this synergy, bradycardia can occur with only mild hyperkalemia combined with therapeutic doses of AV nodal blockers.(32456834)

completing the vicious cycle: bradycardia causes renal failure and hyperkalemia

- Over time, bradycardia may cause hypoperfusion (because bradycardia directly draws down the cardiac output, as discussed further below). Hypoperfusion may promote worsening renal failure. In turn, renal failure will exacerbate the hyperkalemia.

- Overall, this leads to a vicious spiral as shown below. Without treatment, patients may develop progressively worse bradycardia, hyperkalemia, renal failure, and shock. Eventually, this may precipitate frank multi-organ failure.

- This spiral may be even more dramatic among patients who are taking beta blockers which are cleared by the kidneys (e.g., atenolol, nadolol). In that case, renal failure may cause beta blocker accumulation – further accelerating the vicious spiral.

causative factors

- The prerequisites for BRASH syndrome are use of AV nodal blocking medications and presence of risk factors for renal insufficiency.

- Triggers of BRASH may include any cause(s) of renal failure, hyperkalemia, or dose-escalation of AV nodal blocking medications (more discussion of these below).

- The most common underlying substrate for BRASH syndrome is a patient on AV nodal blockers with tenuous renal function. Thus, BRASH tends to occur in relatively fragile elderly patients with hypertension or atrial fibrillation.

- ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) deserve special mention as a risk factor for BRASH syndrome, since they may promote both renal dysfunction and hyperkalemia. Thus, the combination of an ACE inhibitor and beta blocker may set patients up for developing BRASH syndrome if they become ill for another reason (e.g., gastroenteritis).

- With an aging population and lower blood pressure targets for the management of hypertension, BRASH syndrome may become more common over time.

- The exact prevalence of BRASH syndrome is unknown. This is neither a common nor an exceedingly rare diagnosis. My impression is that a moderate-sized ICU will see a handful of cases per year.

- The presentation may span the gamut from patients who are only mildly ill to patients with severe multi-organ failure.

- As in other cardiogenic shock states, most patients will mentate well (even if they are not achieving adequate renal perfusion).

- The dominant feature of any patient's presentation may vary:

- In some patients, the bradycardia and hypotension may be the most notable feature (with only mild hyperkalemia).

- In some patients, severe hyperkalemia may be the most striking feature of the presentation (with only moderate bradycardia and preserved blood pressure).

Diagnosis of BRASH is relatively simple, once one is aware of the syndrome. In particular, BRASH should be considered in any patient who is presenting with bradycardia. The components of the syndrome may easily be identified based on the patient's medication list, vital signs, and basic laboratory data.

Differential diagnosis: This centers around sorting out BRASH syndrome from simple hyperkalemia or from AV blocker intoxication. In reality, these entities occupy a continuum which at times may be impossible to parse out. Some key distinctions are as follows:

BRASH versus simple hyperkalemia

- By itself, hyperkalemia must be rather severe to cause bradycardia (e.g., perhaps over ~7 mEq/L). Alternatively, BRASH syndrome often involves only mild-moderate hyperkalemia acting synergistically with an AV nodal blocker.

- Clinically relevant acute kidney injury and bradycardia suggest a constellation of BRASH syndrome, rather than isolated hyperkalemia.

- An EKG which shows prominent bradycardia without many other features of hyperkalemia may also suggest BRASH syndrome:

BRASH syndrome versus AV blocker intoxication

- AV blocker intoxication involves ingestion of an unusually large amount of AV blockers. Alternatively, BRASH syndrome involves patients who are taking AV blocker medication as directed. Thus, the distinction between AV blocker intoxication vs. BRASH syndrome is often based largely on the patient's history.

Evaluation of the cause is generally more difficult than identifying BRASH syndrome, but this may be essential to proper management. Various causes of BRASH syndrome are listed below. The most common triggers are hypovolemia or medication up-titration. However, some triggers may require more specific management. Thus, it is important to remember that BRASH syndrome is a syndrome rather than a specific diagnosis – so merely identifying BRASH syndrome doesn't mean that you're done! It's still critical to understand why the patient developed BRASH syndrome. Some causes are as follows:

any cause(s) of renal failure 📖

- Pre-renal

- Shock of any etiology (especially hypovolemia, but also sepsis)

- Hepatorenal syndrome

- Abdominal compartment syndrome

- Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura & hemolytic uremic syndrome

- Intrinsic renal failure

- Nephrotoxic medications (e.g., ACEi/ARB)

- Cellular lysis (rhabdomyolysis, hemolysis, tumor lysis syndrome)

- Acute glomerulonephritis

- Acute tubulointerstitial nephritis (ATIN)

- Acute tubular necrosis (ATN)

- Post-renal: Urological obstruction

- Prostatic obstruction

- Nephrolithiasis

any cause(s) of hyperkalemia 📖

- Potassium supplementation

- ACEi/ARB, aliskiren (renin-inhibitor)

- NSAIDs

- Nonselective beta blockers (e.g., labetalol)

- Potassium-sparing diuretics (amiloride, triamterene, spironolactone, eplerenone)

- Antibiotics (e.g., trimethoprim, pentamidine, ketoconazole)

- Cyclosporine, tacrolimus

dose escalation or introduction of AV nodal blocking medication

- Changes in the patient's medication regimen

- Unintended drug-drug interactions

A thorough history and physical examination will usually disclose the cause of the BRASH syndrome (especially if POCUS is used to assess volume status). For example, hypovolemia due to reduced fluid intake seems to be a relatively common cause. In many cases, the trigger will be obvious – making further evaluation unnecessary. If the cause is unclear, then additional evaluation may be needed (e.g., urinalysis, renal ultrasonography, and measurement of creatinine kinase).

key components of therapy:

- Volume management (if necessary).

- Treatment of bradycardia.

- Treatment of hyperkalemia.

- Treatment of any underlying cause(s).

Since BRASH is a vicious cycle, a concerted attack on all components of the cycle is generally very effective in reversing the syndrome. As such, the key is simultaneously deploying simple, noninvasive therapies for each component.

A very common error is to focus on treating just one element (e.g., placement of a transvenous pacemaker to increase heart rate), while ignoring other components of the syndrome. This is far less successful in reversing the overall condition.

most patients require no procedures

- The majority of patients with BRASH syndrome will turn around promptly with several noninvasive medical therapies.

- Note that epinephrine, isoproterenol, and dobutamine are fairly safe for peripheral administration (more on this below). Thus, central access is not required solely to administer one of these agents.

- Aggressive medical therapy is often able to avert the need for procedures (e.g., transvenous pacing or hemodialysis).

central & arterial access for the sickest patients

- A small subset of the sickest patients with BRASH syndrome and multi-organ failure may benefit from central venous access and an arterial catheter (to facilitate vasopressor titration).

- Treatment of BRASH requires the administration of numerous IV medications (e.g., diuretics, bicarbonate, calcium) – so inadequate IV access can delay prompt treatment.

- A good option for these patients is often placing adjacent catheters into the femoral artery and vein (using a single sterile site; more on this here). Patients with BRASH syndrome will typically recover within 12-24 hours, with no requirement for long-term central access. Thus, the lines can be removed promptly, avoiding any concerns regarding line infection or deep vein thrombosis when accessing the femoral vein.

assess volume requirement based on POCUS and history

- Volume status varies dramatically among patients with BRASH syndrome:

- Volume depletion is a common trigger for BRASH syndrome (e.g., due to gastroenteritis). Such patients may require aggressive fluid resuscitation.

- Some patients will present following several days of oliguric renal failure, leading to fluid retention. Such patients may be volume overloaded (and, indeed, they may have progressed to the point of developing congestive nephropathy). Diuretics without any fluid administration may be helpful here – both to remove potassium and also to re-establish euvolemia.

- POCUS and clinical history may be useful to estimate volume requirements. Points of interest may include:

- Cardiac ultrasonography (including both IVC diameter and also overall cardiac function).

- Recent weight gain or weight loss.

- Peripheral edema.

- Changes in fluid intakes or losses (e.g., poor oral intake or diarrhea).

if hypovolemic: fluid selection using pH-guided fluid resuscitation

- pH-guided resuscitation is the concept of choosing a fluid which will treat pH abnormalities (discussed further here, and illustrated below).

- Many BRASH patients initially have a uremic acidosis, so isotonic bicarbonate is often an excellent resuscitative fluid for them. Isotonic bicarbonate is typically formulated by adding 150 mEq sodium bicarbonate to a liter of D5W (more on isotonic bicarbonate here). Isotonic bicarbonate may be given rapidly to patients with profound volume depletion (e.g., 1,000 ml/hour). Benefits of isotonic bicarbonate may include:

- a) Isotonic bicarbonate will improve the pH status (potentially averting the need for dialysis to manage acidosis).

- b) Isotonic bicarbonate will directly reduce the potassium (due to dilution and shifts of potassium into the cells).

- c) Isotonic bicarbonate may indirectly reduce the potassium (increased secretion of bicarbonate into the urine promotes excretion of potassium).

- Lactated Ringers may be useful in the following situations:

- (1) Patients with volume depletion and a normal acid-base status.

- (2) Patients with metabolic acidosis which has resolved following administration of isotonic bicarbonate, and who continue to have ongoing volume depletion.

if volume overloaded: diuresis alone

- Nearly all patients with BRASH syndrome will need diuresis, to promote excretion of potassium (more on this below).

- For patients who are initially hypovolemic or euvolemic, urine losses following diuresis should be replaced with crystalloid (either isotonic bicarbonate or lactated Ringer's, depending on their pH status).

- For patients who are initially hypervolemic, then diuresis alone may be used to control both hyperkalemia and volume overload.

IV calcium

- The primary role of calcium is to counteract the effects of hyperkalemia on the myocardium. Calcium might also have some effectiveness as an antidote to AV nodal agents (e.g., calcium channel blockers).

- The appropriate dose of calcium might be roughly estimated based on the severity of the hyperkalemia:

- Patients with mild/moderate hyperkalemia may require less calcium.

- Patients with severe hyperkalemia and multiple EKG changes (e.g., widening of the QRS complex) may require higher doses and repeated doses of calcium.

- Initial dose of calcium:

- 1 gram IV calcium chloride (ideally through a central line, but it may also be given peripherally in a crashing patient).

- 3 grams IV calcium gluconate (preferred agent for peripheral IV administration, because it causes fewer problems if it extravasates).

- Further doses of calcium may be indicated for persistent bradycardia.

- The ideal dosing here is unknown. An expert guideline recommended re-dosing once or twice if needed, while admitting the lack of evidence.(27693804)

- In general, hyperkalemia is more dangerous than hypercalcemia, so you're probably better off erring on the side of hypercalcemia. If you have a point-of-care electrolyte monitor available, check calcium levels and avoid pushing the ionized calcium above >3 mM.

- Patients with hyperphosphatemia may be at risk of developing calciphylaxis (precipitation of calcium phosphate), so a bit more caution with IV calcium may be appropriate in these patients.

- Intravenous calcium lasts only 30-60 minutes, so it may need to be repeated.

(don't bother with atropine)

- Don't waste your time with atropine here (unless it is the only agent available to you).

- Reasons not to use atropine:

- 1) Atropine may be ineffective.

- 2) If atropine works, it will tend to wear off over time (so the patient will improve, but then crash again later on).

- 3) Atropine isn't readily titrated.

- 4) Atropine doesn't shift potassium into the cells.

- More discussion of why not to use atropine in crashing patients here.

epinephrine or isoproterenol if hypotensive

- Epinephrine infusion is generally a useful front-line therapy for patients with bradycardia and hypotension. Advantages include:

- (a) Epinephrine increases heart rate.

- (b) Epinephrine stimulates beta-2 receptors, causing potassium to shift inside cells.

- Isoproterenol is arguably better, but it is extremely expensive in the United States. Advantages of isoproterenol include:

- (a) Isoproterenol seems to be a more powerful chronotrope than epinephrine. Thus, there appears to be a group of patients who may not respond to epinephrine, but who will respond to isoproterenol.

- (b) Isoproterenol is a pure beta-agonist. Unlike epinephrine, isoproterenol lacks any alpha-agonist (vasoconstrictive) properties. For a patient whose problem is bradycardia, a pure chronotrope might be ideal to maximize systemic perfusion (while avoiding hypertension).

- Both epinephrine and isoproterenol are safe for peripheral infusion.

- Other beta-agonists could be considered if epinephrine or isoproterenol are unavailable (e.g., continuous albuterol nebulization).

dobutamine or isoproterenol for occult bradycardic shock

- Some patients with bradycardia will develop occult bradycardic shock, as explained in the figure above. This involves the following components:

- (1) Severe bradycardia (of any etiology)

- (2) The patient compensates for the bradycardia by developing severe systemic vasoconstriction (occasionally this may even induce hypertension!). Systemic vasoconstriction succeeds at supporting the blood pressure, but the cardiac output is still inadequate.

- Occult bradycardic shock may be identified among patients with the following characteristics:

- (1) Ongoing significant bradycardia.

- (2) Blood pressure is normal or high.

- (3) Signs of systemic hypoperfusion (e.g., cold extremities, poor urine output).

- Treatment of occult bradycardic shock requires a positive chronotrope without any vasoconstrictive properties.

- Isoproterenol is an ideal drug for this, if it's available (discussed above).

- Dobutamine is also a good option here.

- ⚠️ Failure to diagnose and manage occult bradycardic shock may cause diuretics to fail due to inadequate renal perfusion, ultimately precipitating worsening renal failure and hemodialysis.

(transvenous pacing)

- Transcutaneous or transvenous pacing is indicated for hemodynamically unstable bradycardia which is refractory to medical therapies.

- Transvenous pacing is rarely (if ever) needed in BRASH syndrome. Transvenous pacing can generally be avoided by using a combination of IV calcium and beta-adrenergic agents as outlined above.

- If the patient truly requires transvenous pacing, consider the possibility of an alternative diagnosis entirely (e.g., Lyme disease).

More on the treatment of bradycardia here.

- Factors affecting how aggressive to be in treatment of hyperkalemia

- (1) The severity of the hyperkalemia (which may vary from mild to severe).

- (2) The degree of acute kidney injury (more severe renal failure will make it harder to treat the hyperkalemia).

- (3) The amount of isotonic bicarbonate required (isotonic bicarbonate will draw down the potassium, so patients who require resuscitation with isotonic bicarbonate may require less aggressive therapy for hyperkalemia).

- Based on the above variables, treatment of hyperkalemia will vary quite a bit. For example:

- In a patient with mild/moderate hyperkalemia and mild kidney injury, a few doses of furosemide and some additional fluid may be sufficient to resolve the hyperkalemia.

- In a patient with severe hyperkalemia and severe renal injury, multiple high doses of diuretic may be needed (or occasionally even dialysis).

- Proper kaliuresis involves volume resuscitation, re-establishment of renal perfusion, and diuretic administration. Fluid resuscitation and bradycardia management are discussed above, but don't forget that these are key elements in successful kaliuresis.

- ⚠️ Diuretics alone will often fail if the patient is under-resuscitated and malperfused.

- Dialysis can generally be avoided with multimodal therapy for all components of BRASH syndrome. However, some patients with severe renal injury won't respond to the diuretic bomb and will therefore need emergent dialysis.

For treatment options, see the chapter on hyperkalemia here.

Additional interventions to reverse beta blocker and calcium channel effects are listed below. These should generally not be required for BRASH syndrome management, but rather they are intended more for medication intoxication. In unclear circumstances where the patient isn't responding to any other therapy, they might nonetheless be considered.

- Glucagon or milrinone:

- These agents increase cardiac intracellular cyclic AMP levels, thereby bypassing the beta receptor.

- Theoretically, they could be used for refractory bradycardia in a patient on beta-blockade therapy.

- Their efficacy is unclear.

- Drawbacks include emesis (glucagon) and vasodilation, which may cause hypotension (milrinone)

- Hyperinsulinemic euglycemic therapy:

- Insulin does have the advantage of potentially reversing the effects of beta blockers or calcium channel blockers, while simultaneously reducing the potassium.

- Lipid emulsion.

Follow us on iTunes

The Podcast Episode

Want to Download the Episode?

Right Click Here and Choose Save-As

To keep this page small and fast, questions & discussion about this post can be found on another page here.

- Unfortunately, BRASH syndrome is often misdiagnosed as isolated hyperkalemia or isolated bradycardia. These diagnoses recognize only part of what is going on, leading to a failure to treat the entire syndrome.

- Standard ACLS strategies for bradycardia may fail to work in patients with BRASH syndrome, since they don't incorporate the use of IV calcium.

- A common pitfall is rushing to place a transvenous pacemaker for bradycardia before attempting to treat medically (e.g., with epinephrine and IV calcium). Transvenous wires are very rarely required for these patients.

- Another pitfall is failure to rapidly restore a normal heart rate and perfusion (which often requires epinephrine or dobutamine). Even if the blood pressure is OK, as long as the patient is severely bradycardic they are probably malperfusing their kidneys.

- Avoid volume resuscitation with normal saline (this will worsen acidosis and hyperkalemia as discussed here and here).

Guide to emoji hyperlinks

= Link to online calculator.

= Link to Medscape monograph about a drug.

= Link to IBCC section about a drug.

= Link to IBCC section covering that topic.

= Link to FOAMed site with related information.

= Link to supplemental media.

Going further

- Relevant IBCC chapters

- BRASH syndrome (PulmCrit blog)

- BRASH syndrome (WikEM)

- BRASH syndrome (EM:RAP)

- An elderly woman found down with bradycardia and hypotension (Steve Smith's ECG blog)

References

- 27693804 Rossignol P, Legrand M, Kosiborod M, Hollenberg SM, Peacock WF, Emmett M, Epstein M, Kovesdy CP, Yilmaz MB, Stough WG, Gayat E, Pitt B, Zannad F, Mebazaa A. Emergency management of severe hyperkalemia: Guideline for best practice and opportunities for the future. Pharmacol Res. 2016 Nov;113(Pt A):585-591. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.09.039 [PubMed]

- 31403103 Diribe N, Le J. Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole-Induced Bradycardia, Renal Failure, AV-Node Blockers, Shock and Hyperkalemia Syndrome. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2019 Jul 22;3(3):282-285. doi: 10.5811/cpcem.2019.5.43118 [PubMed]

- 31975993 Zaidi SAA, Shaikh D, Saad M, Vittorio TJ. Ranolazine Induced Bradycardia, Renal Failure, and Hyperkalemia: A BRASH Syndrome Variant. Case Rep Med. 2019 Dec 31;2019:2740617. doi: 10.1155/2019/2740617 [PubMed]

- 32201662 Sattar Y, Bareeqa SB, Rauf H, Ullah W, Alraies MC. Bradycardia, Renal Failure, Atrioventricular-nodal Blocker, Shock, and Hyperkalemia Syndrome Diagnosis and Literature Review. Cureus. 2020 Feb 13;12(2):e6985. doi: 10.7759/cureus.6985 [PubMed]

- 32456834 Flores S. Anaphylaxis induced bradycardia, renal failure, AV-nodal blockade, shock, and hyperkalemia: A-BRASH in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2020 May 16:S0735-6757(20)30375-2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.05.033 [PubMed]

- 32467792 Prabhu V, Hsu E, Lestin S, Soltanianzadeh Y, Hadi S. Bradycardia, Renal Failure, Atrioventricular Nodal Blockade, Shock, and Hyperkalemia (BRASH) Syndrome as a Presentation of Coronavirus Disease 2019. Cureus. 2020 Apr 24;12(4):e7816. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7816. PMID: 32467792; PMCID: PMC7249758 [PubMed]

- 32094236 Srivastava S, Kemnic T, Hildebrandt KR. BRASH syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2020 Feb 23;13(2):e233825. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2019-233825 [PubMed]

- 32565167 Farkas JD, Long B, Koyfman A, Menson K. BRASH Syndrome: Bradycardia, Renal Failure, AV Blockade, Shock, and Hyperkalemia. J Emerg Med. 2020 Aug;59(2):216-223. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.05.001 [PubMed]

- 32712747 Schnaubelt S, Roeggla M, Spiel AO, Schukro C, Domanovits H. The BRASH syndrome: an interaction of bradycardia, renal failure, AV block, shock and hyperkalemia. Intern Emerg Med. 2020 Jul 25. doi: 10.1007/s11739-020-02452-7 [PubMed]